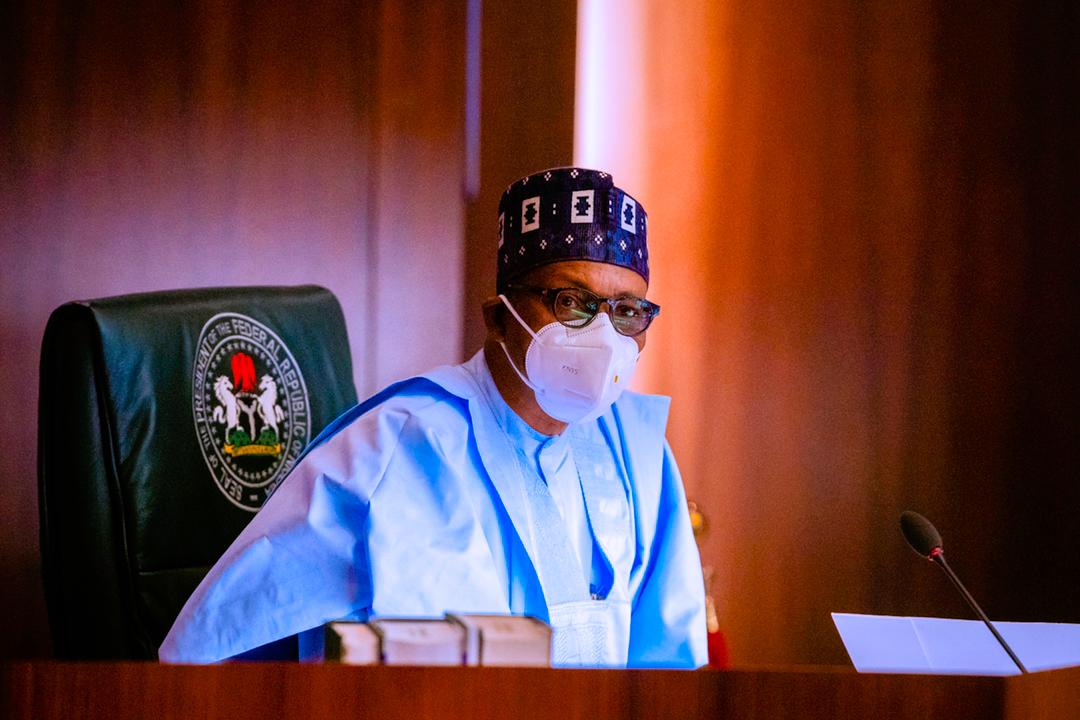

I was going to congratulate President Muhammadu Buhari for finally getting rid of his security chiefs. Together with them, he had authored Nigeria’s most insecure chapter since the civil war.

The Boko Haram insurgency grew worse. Kidnapping became an industry. Armed robbery returned. Cattle herdsmen began to carry AK-47s to overrun farms and communities.

- What bandits commanders told me in Zamfara forests Sheikh Gumi

- Top bandits commander, Buharin Daji, to lay down arms soon Matawalle

So bad did things grow that at different times, Mr. Buhari and Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo ordered the security chiefs to relocate to the troubled northeast and prosecute their assignments from there. Curiously, the chiefs ignored the chiefs of state, without repercussion.

The militants carried on an easy campaign of attacking communities and military and police formations, as well as seizing and carting away citizens and valuable equipment.

Governors and community leaders cried out, but nothing improved. The security chiefs quietly slipped back into Abuja, where they enjoyed the pomp and circumstance of their offices while Aso Rock pretended nothing was wrong.

Nigerians wept in public and begged Buhari to change his underachieving service chiefs, but he refused.

That was until 12 days ago when he finally accepted their “resignation” and announced their replacements. He told the new chiefs, in an admission he was making for the first time, that Nigeria was in a “state of emergency”.

The problem is that as events unfolded, Buhari once again seemed to affirm that the “past is prologue,” as he first declared at his first inauguration. Shockingly, the Nigerian leader’s courage seemed to last only 10 days: on Thursday, he nominated all of them as non-career ambassadors.

If keeping the four men: Gabriel Olonisakin, Tukur Buratai, Ibok Ibas and Abubakar Sadique in office for so long was a crime, seeking to appoint them ambassadors is a betrayal of the country.

This is because it is clearly an effort to shield them from prosecution by the International Criminal Court for atrocities and rights abuses committed during their tenure in the past five years.

If Nigeria needs diplomats, it is in the career—not non-career—category, and there is no self-respecting country that would accept these appointments to their territory. If the Senate has any sense of responsibility or pride, it will refuse to confirm the nominations.

The nominations remind Nigerians and the international community how such a promising nation lost its way under Buhari. It is a reminder that Buhari focuses on the past, not the future; that his energies, if any, are on the ghosts of the past not the challenges of the present.

It is why Buhari is such a flawed ruler, and why the emerging war over herdsmen will test abilities he clearly lacks. It may seem like a different lifetime now, but it was only in 2018, on New Year’s Day, that over 70 Nigerians were massacred in Benue State.

What did Buhari do? Well, two things. First, he called to Abuja certain leaders of the Benue people, and—in effect—blamed the victims, urging them to “accommodate your countrymen” (the armed herders) and “restrain your people.”

Second: he deployed to Benue State Inspector-General of Police Ibrahim Idris to enhance security.

And what did Idris do? The IGP was not going to leave his luxury lifestyle in Abuja, so he refused to go. It took Buhari several weeks to “discover” (wink!) that the IGP never left Abuja, he said.

And yes, IGP Idris still did not leave Abuja. And there was nothing Buhari could do about it.

Accommodate your countrymen? Restrain your people?

That was how Buhari responded locally, but under pressure internationally, he and his government deployed different tales. For instance, in April 2018 in London, as Buhari visited his good friend Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, he basically confessed that the menacing herdsmen were trained killers, and that they had been trained and armed by former Libya leader Muammar Gaddafi.

“When [Gaddafi] was killed, the gunmen escaped with their arms,” Buhari said. “We encountered some of them fighting with Boko Haram.”

Two months later, an outbreak of violence in Plateau State claimed over 200 lives. [Previously, in December 2010 and January 2011, the same area had suffered the same kind of brutal violence, with the same results.]

At the general debate of the United Nations General Assembly that September, Buhari expanded his theory to the Heads of State and Government, telling them that the insurgencies in the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin featured “runaway fighters from Iraq and Syria and arms from the disintegration of Libya”.

But that was not the story that Information Minister Lai Mohammed told the world in London that autumn. He cited no foreign arms or Gaddafi or Syria. The ongoing insecurity, he said, was “(largely) population explosion, climate change and criminality, as against the naysayers’ position that it is ethnic or religious.”

As Buhari enthrones new security chiefs but focuses on protecting the previous, the herdsmen crisis is emerging as the nation’s pre-eminent security problem, following last month’s ultimatum by Governor Rotimi Akeredolu of Ondo State demanding that all herders vacate forest reserves in the state within seven days.

The truth is simply that insecurity continues to spiral out of control, with the so-called herders in the middle of it, along with the refusal of the federal government to determine who or what the term means.

Remember that since Buhari took office, his government’s response has included grazing reserves or colonies, settlements, and the Rural Grazing Area programme. None of them made sense or attracted widespread support partly because it was unclear whether the proposal concerned Nigerians herding cattle, or Libyans and Syrians armed to overrun Nigerian sovereignty and peace.

My vote is for peace and security for all Nigerians. Unfortunately, Buhari has not demonstrated that this is a concept he embraces. If it were, perhaps the current crisis would not have continued to spill southwards, outwards and out of control.

First, the element of arms must be eliminated from animal husbandry in Nigeria. It is not about the herders being Fulani, but about herders being armed and violent and entitled. Herders that are better armed than the military and the police must be purged by definition and law. The government cannot protect and promote so-called herders—particularly if they are armed and vicious—at the expense of communities and farmers.

In September 2019, the government launched the National Livestock Transformation Plan, which was to be implemented in a the pilot states of Adamawa, Benue, Kaduna, Plateau, Nasarawa, Taraba and Zamfara. I do not see how that effort involved arms and ammunition anywhere in Nigeria.

This is the problem Buhari problem has. While demonstrating no serious effort to control the killings by the herdsmen in Nigeria, he has offered excuses that have the effect of granting them the latitude to continue to menace and kill.

But neither herders nor militants will assume ownership of Nigeria. It is now up Buhari to recognize the abyss into which his personal and official story now stares.

This column welcomes rebuttals from interested government officials.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.