The loss of human resources for health to brain drain is affecting primary health care service (PHC) delivery in many rural communities of the country, particularly for maternal and child health services.

By Ojoma Akor (Abuja), Abubakar Akote (Minna), Haruna Gimba Yaya (Gombe), Mumini AbdulKareem (Ilorin) & Eyo Charles (Calabar)

Daily Trust on Sunday reports that a lot of nurses and midwives, medical doctors, and other health care workers have either migrated out of the country for greener pastures or from rural health centres to secondary and tertiary hospitals in urban areas in the last few years, causing dearth of the needed manpower at the facilities.

JUST IN: Brazil’s Pereira ends UFC reign of Nigeria’s Israel Adesanya

APPLY NOW: Orodata announces ‘Climate’ Journalism Fellowship

Investigations also revealed that the challenges of human resource for health are affecting the roll out of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) at the various PHCs.

The BHCPF is a federal and state-funded initiative. It is a key component of the National Health Act 2014, and has the objective of ensuring the provision of a basic minimum health package for Nigerians, strengthening the primary health care system and providing emergency medical treatment.

It is derived from a minimum of one per cent of the federal government’s Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF). At the PHCs, those enrolled in the BHCPF are covered to receive antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care for pregnant women, as well as immunisations and treatment for malaria, pneumonia, measles and dysentery for children under five.

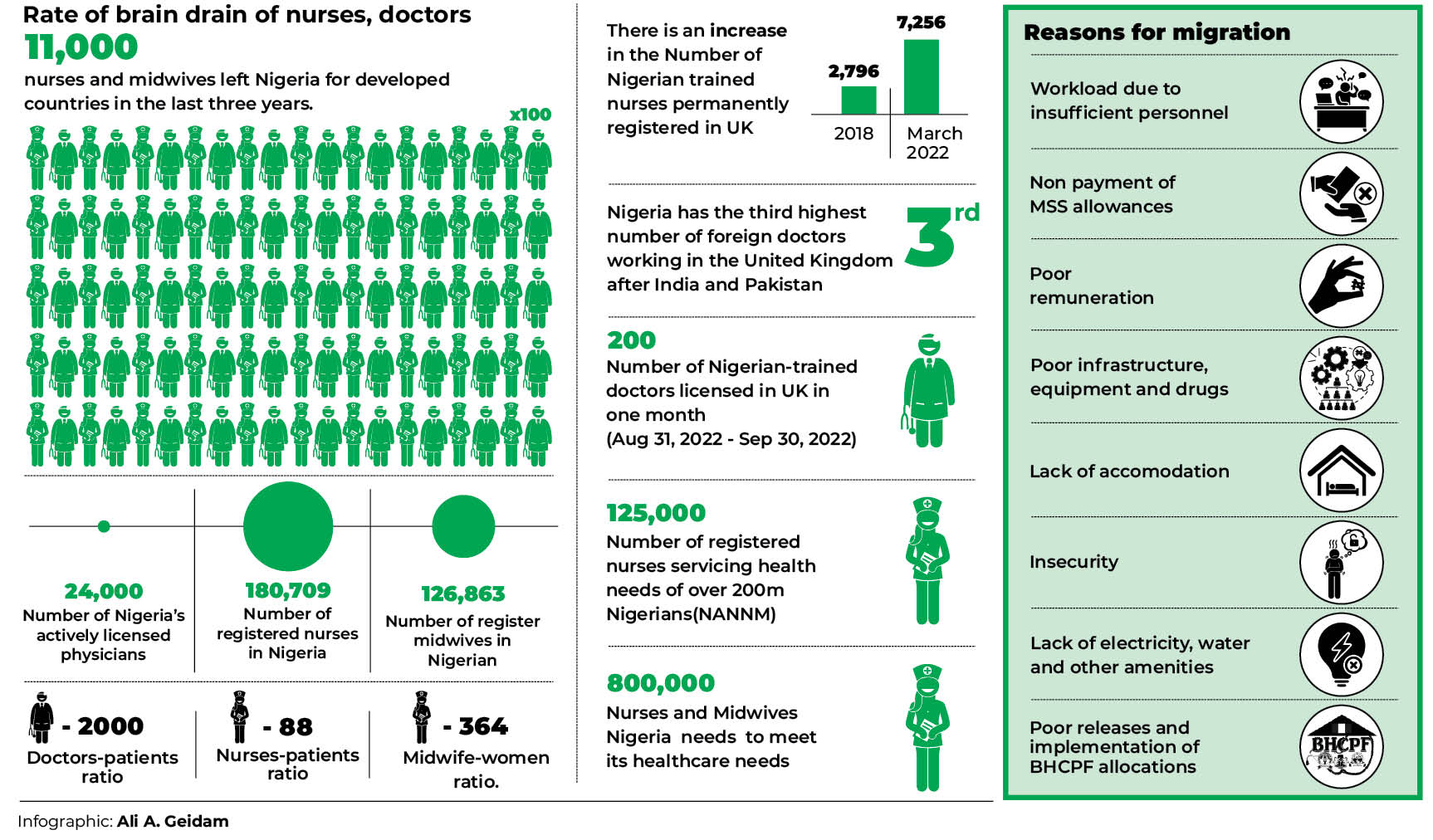

Rate of brain drain of nurses, doctors

According to a research titled, ‘Brain drain of Nigeria’s Human Resource for Health: Implications for Child and Family Health’ conducted by the development Research and Projects Centre (dRPC) via the Partnership for Advocacy in Child and Family Health at Scale (PACFaH@Scale) programme, about 11,000 nurses and midwives left Nigeria for developed countries in the last three years.

“A report by the United Kingdom (UK) Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) has revealed that as at March 2022, the number of Nigerian trained nurses who are now on the UK permanent register has increased from 2,796 in 2018 to 7,256 as at March 2022,” it stated.

The report also revealed that as at3March 2020, the Federal Ministry of Health put the number of registered nurses in Nigeria at 180,709, which implies a ratio of 88.1 nurses per 100,000 population (88:100,000).

“On the Nigerian Midwife register, there are only 126,863 midwives. With 23 per cent or 46,216,830 of Nigeria’s female reproductive age population, there is only one midwife to every 364 women of reproductive age.”

The report also states, “In 2021, the National Association of Nigerian Nurses and Midwives (NANNM), lamented that there were only about 125,000 registered nurses servicing the health needs of the country’s over 200 million population. This meant that the country would need at least 800,000 nurses and midwives to meet its healthcare needs.”

The dRPC study also showed that the number of Nigerian-trained nurses who left Nigeria for the UK was the third highest in the world and highest in Africa, adding that the mass relocation of trained nurses undoubtedly has enormous implications for the health care sector, which is already understaffed.37

According to the report, currently, Nigeria has the third highest number of foreign doctors working in the United Kingdom, after India and Pakistan.

Data from the General Medical Council (GMC), the body responsible for licensing and maintaining the official register of medical practitioners in the United Kingdom reported licensed 200 Nigerian-trained doctors in one month between August 31, 2022 and September 30, 2022.

The president of the Nigeria Medical Association (NMA), Dr Ojinmah Uche, said Nigeria had about 24, 000 actively licensed physicians caring for its over 200 million population as a result of brain drain in the country.

He said this gave a horrible ratio of approximately 1 doctor to 10,000 patients.

“Only one doctor is incredibly available to treat 30,000 patients in some states in the South, while states in the North are as worse as one doctor to 45,000 patients. In some rural areas, patients have to travel more than 30kilometers from their abodes to get medical attention where available, thus Nigeria making access to health care a rarity,” he said.

Dr Ojinmah said that based on the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) established minimum threshold, a country needs a mix of 23 doctors, nurses and midwives per 10,000 population to deliver essential maternal and child health services.

Insufficient personnel, poor remuneration threaten BHCPF, PHCs in Gombe

When Khadijah Haruna graduated as a midwife from the College of Nursing and Midwifery, Gombe, she and other four other course mates were posted to a PHC in Kwadon in Yamaltu/Deba Local Government Area of the state, under the federal government’s Midwives Service Scheme (MSS).

On arrival at the facility, they found that they were the only certified midwives qualified to attend to hundreds of pregnant women that turned out at the health centre daily for both ante-natal and post-natal services.

For the one year they worked at the facility, they were always overworked, could not run shifts, coupled with scarcity of accommodation, so they had to shutte from Gombe to Kwadon (about 20 kilometres) daily.

Khadijah said only about 50 per cent of the equipment at the facility were working, as such, they could not perform basic procedures, such as Manual Vacuum Aspiration (MVA) for pregnant women with stillborn, and had to mostly refer the patients to other secondary health facilities in Gombe.

“Up to the time we finished the one-year MSS, I was never paid the sum of N30,000 each by the federal and state government as MSS allowance as stipulated in the condition of service.

“We also didn’t get upgrade to staff allowance during the one year in Kwadon; we were left with the paltry students’ allowances of N20,000,” she said.

For Rashida Hussaini, when she graduated as a midwife from the College of Nursing and Midwifery, Gombe, she and another colleague were posted to a health facility in Dukku Local government Area.

“We met five other midwives at the hospital but we were not enough for a facility that requires at least 10 midwives and nurses to function effectively and attend to numerous patients,” she said.

She said the delivery bed at the facility was rusting and the entire maternity ward needed a total overhaul. There is also no running water in the facility that receives a lot of deliveries on a daily basis.

Therefore, within the first month of reporting to the PHC in Dukku, Rashida’s colleague sought transfer to Gombe.

“We couldn’t cope with the volume of work and the lack of accommodation. We were also not receiving the MSS allowances; we were still on the meagre students’ allowance of N20,000,” Rashida added.

At end of the one year, she hastily returned to join most of her other colleagues in Gombe, who had also migrated from the rural posting due to number of factors, notably lack of accommodation and poor working environment.

On his part, Shehu Ahmad was posted to Nafada Local Government Area, his local government of origin.

When Ahmad arrived at one of the health care centres in Nafada, he faced challenges, such as dearth of basic equipment at the facility and lack of manpower, which he said “made one to work as a doctor, nurse, attendant and cleaner at the same time.

“I worked for almost 24 hours daily. The nurses at the facility were grossly inadequate to cater for the high number of patients turning over for treatment. There were only four nurses working at the facility, making shifts too difficult,” he said.

He added that the only few doctors posted to the facility hardly stayed. They only visited for two days in a whole month, leaving the quantum of work to the few nurses there.

He said all the principal officers in the clinic hardly stayed, with the head of Nursing Service (HNS) and secretary of the facility visiting once in a week from Gombe.

He added that the bad road linking Nafada to Gombe also played a role, making referral from health facilities in the local government area to other general hospitals around Nafada very difficult. Most patients die on their way to the hospitals, he said.

“Even the general hospital in Bajoga has stopped receiving our referrals because they also lack enough manpower,” he said.

Also, due to lack of accommodation, nurses share rooms at the facility’s staff quarters.

For the two years he worked in Nafada, over 1,000 kilometres from Gombe, Ahmad was not upgraded to collect a staff salary of N65,000, instead, he was collecting the students’ allowance of N20,000 monthly.

When he could no longer cope with the problems, he sought for a transfer to Gombe.

Musa Abubakar, another nurse now working in a tertiary hospital said he worked in three cottage hospitals at Hinna town in Yamaltu/Deba Local Government Area, Biri in Nafada and Malam Sidi in Kwami after graduation.

“At the Malam Sidi Cottage Hospital, there are only 12 nurses and midwives, whereas the facility needs at least 30 nurses and midwives to work effectively and also run the three shifts, plus off days,” he said.

He narrated that due to the lack of manpower, nurses were left with no option than to hand over duty to other cadres at the end of their shifts, adding, “And these people are not efficiently trained to handle such cases; they complicate things most times.”

While saying that accommodation is a major challenge forcing people to seek for transfer from rural areas to urban centres, he lamented, “For the five years I worked in these rural communities across three local government areas, I have never received allowance for rural posting, which is a meagre N7,000, which is not even encouraging to keep someone in rural areas.”

He added that there were also no social amenities like electricity, adequate potable water, “coupled with the precarious security situation in the country, making health workers to stay away from health facilities in rural areas.”

“Therefore, if one managed to stay for a maximum of two years, he or she would lobby for redeployment,” he added.

Findings by Daily Trust on Sunday also revealed that almost all the PHCs benefitting from the BHCPF in 11 local government areas in the state lack qualified medical doctors and auxiliary health care workers to provide services.

Most of the PHCs visited lack equipment and running water. They rely on unclean water from vendors for medical activities and personal use.

The officer-in-charge in one of the PHCs told Daily Trust on Sunday that there were only 12 health workers at the facility, whereas it needs at least 30 personnel to run its three shifts effectively.

‘Gombe govt recruits 440 health workers’

The Gombe State Government recently recruited over 440 new health workers, comprising of 106 midwives, 213 CHEWs, 132 JCHEWs, who will be deployed to the various PHCs to address some of the challenges and reposition the sector for improved performance.

The state Commissioner for Health, Dr Habu Dahiru, said the recruitment was as a result of the Governor Muhammadu Inuwa Yahaya administration’s belief that primary health care is the bedrock of the health system, “and that an effective and high performing PHC translates to increased productivity, longevity and survival.”

“We are looking into the human resource issue, focusing on the schools and colleges that produce the medical doctors and other health workers, where the nurses, midwives and CHEWs were produced,” Dr Dahiru said.

The executive secretary of the Gombe State Primary Health Care Development Agency (GSPHCDA), Dr Abdulrahman Shuaibu, said the state government had upgraded not less than 114 PHCs for optimal performance.

Manpower migration hinders access to quality health care in Niger PHCs

In Niger, investigation by Daily Trust on Sunday revealed that dozens of doctors, nurses and midwives have migrated out of the state in the last two years, leaving the PHCs in the hands of few community health workers.

The executive director, Niger State Hospitals Management Board, Dr Ibrahim Abdullahi, said some of the doctors, midwives and nurses left without notifying the board or the state until they assumed work in their new places of work.

“They just informed us to terminate their appointments. Some female nurses and midwives just applied for maternity leave or annual leave and didn’t come back,” he said.

A medical doctor in one of the government-owned hospitals in Minna told our correspondent on the condition of anonymity that shortage of health personnel was making the remaining ones overworked and stressed.

It was gathered that this year alone, 9 doctors with vast experiences left the IBB Specialist Hospital, Minna in pursuit of greener pastures. A nurse manages between 30 and 32 patients in a night at the hospital.

At the Paiko Model Primary Health Care Centre, for instance, one of the accredited centres for the BHCPF, one midwife attends to over 500 pregnant women during antenatal services.

A staff who spoke on the condition of anonymity told Daily Trust on Sunday that, “Our antenatal unit is being managed by only one midwife. Sometimes we have to assist her there because she cannot do it alone.”

The story in Etsu-Audu Primary Health Care Centre, one of the focal facilities, a BHCPF accredited centre in Gbako Local Government Area, was also abysmal and manned by only one CHEW.

Pregnant women and children with severe cases were always referred to Bida General Hospital or Lemu Rural Hospital, about 18km and 24km respectively.

The head of the centre, Joshua Ndana Tsado, said the facility did not receive the BHCPF every month, adding, “Sometimes we receive money quarterly, but since the last few quarters, we have not received any,” he said.

On staff strength, he said there were 14 staff in the facility, out of which two people that work in the laboratory were voluntary. Two CHEWs and two J-CHEWs are also voluntary.

“We will appreciate it if the government can send a medical doctor to us as it will save the lives of pregnant women and help the entire community. This is because before you make referral sometimes, some people die, and it is not everything that I can do as a CHEW,” he said.

In Maitumbi Primary Health Care, an accredited centre for the BHCPF in Minna, patients rely on 11 permanent staff, including a nurse and midwife and voluntary staff to attend to over 50 pregnant women who come for antenatal care on Wednesdays. There is also lack of space and beds.

The story was the same at the Tudun-Fulani Gabas Primary Health Care Centre. The centre has dilapidated infrastructure, lacks water and working tools, including a digital thermometer.

A nursing mother said, “We buy drugs, except the family planning and anti-malaria ones. We get immunisation free. My sister had just given birth and we are buying drugs.”

The executive director, Niger State Primary Health Care Development Agency, Dr Ibrahim Ahmed Dangana, confirmed the dearth of manpower in primary health care centres, saying the state government was already planning to recruit more personnel.

He said the implementation of the BHCPF in the state was excellent, adding, “274 focal facilities are benefitting from the fund. Monies are regularly disbursed to them in line with what we call business development plan, and quality improvement plan to ensure availability, accessibility and affordability of qualitative primary health care services in Niger State.”

He said the state government had put in place ‘Task Shifting and Task Sharing’ policy, so there wouldn’t be gaps in terms of service delivery.

Dangana said the state recently conducted interview for 2,000 candidates, adding, “Now, the emphasis on midwives so that they would provide qualitative antenatal care and safe labour and delivery services in these facilities.”

Ondo’s recruitment of health workers improves PHCs, BHCF

John-Mohanye Adenike at the Comprehensive Health Centre, Oke-Ijebu, Akure, Ondo State, said the number of nurses had grown from two to four following the last employment, but the facility still needed more staff and water.

She explained that the implementation of the BHCPF had been okay as the facility provides free delivery, immunisation, drugs and other services.

Nike Adeyemi at the Orita-Obele Health Centre, Akure, said the community was recording an increase in maternal deaths because traditional birth attendants (TBAs) were still handling some of the clients that are supposed to come to the health centres.

Adaraniwon Bamigbe at the BHCPF centre, Ipinsha, Akure South Local Government Area of Ondo State, said the major problem they were facing was shortage of personnel, and called on government to provide non-technical and technical staff.

Dr Omosehin Adeyemi-Osowe, the chairman of the NMA in Ondo State, and the director of the PHC for the Akure South Primary Health Care Authority, said primary health care in the state had improved greatly as the governor employed health workers last year.

While describing it as the single largest employment in the primary health care system in Ondo State since creation, he said that in the last three years, equipped laboratories, as well as generators and ultrasound machines had been provided in PHCs in the 18 local government areas.

He added that the basic health provision fund had also helped to improve service delivery.

“I can affirm that in Ondo State, the basic health care provision fund is well implemented. It has provided us a platform to do a lot of things, especially for patients. The evidences abound,” he said.

He said 195 PHCs were benefiting from the fund, but however, appealed for more facilities to be included .

Dr Francis Adegoroye Akanbiemu, the permanent secretary of the Ondo State Primary Health Care Development Agency, said that measures put in place by the government was helping to reduce brain drain, and the BHCPF is also being judiciously used in the state.

“It is federal government’s fund, so they send auditor regularly to audit how it is being spent.”

Kwara recruits nurses and midwives to address deficit

The shortage of doctors, nurses and midwives is affecting services in PHCs in Kwara State. Some of them lack drugs to treat common diseases as well as water, electricity and incinerators.

The matron of the health centre, Alanamu, Mrs Apata Aishat said, “Initially, we used to have doctors, but during the COVID-19 period they all left and never came back. We are also short of nurses. For instance, we have up to six nurses here, but most of them are programme officers with their hands already full from the services they conducted in that capacity.

“The main nurse we have here is presently bereaved and not available, leaving the huge workload for those that are around. There was one we were managing with before, but she has been transferred to the Balogun Alanamu Health Centre, which was recently commissioned.”

When Daily Trust on Sunday visited the PHC in Ojagboro, Ilorin East Local Government Area, patients were only attended to by nurses and some drugs were not available.

The executive secretary of the Kwara State Primary Health Care Development Agency, Dr Nusirat Elelu, said the state had 175 accredited PHCs for the BHCPF, with the additional 17 facilities that were recently accredited. She said the plan was to ensure that all of them had the infrastructural and human resources needed.

Elelu said 44 midwives were recently recruited by the state government to improve the quality of services under the BHCPF.

Inadequate personnel, bane of PHC in Cross River

In Cross River State, many of the facilities in rural areas are bedeviled by inadequate personnel and poor infrastructure.

A resident of Creek Town in Odukpani Local Government Area of the state, Hogan Cobham, a teacher, said health workers, including nurses, hardly came to the centre.

He said, “The day they remember to come, they will spend one or two hours, then hurry and leave. They won’t return until perhaps when they hear an official of the government would be visiting.

“Our people, especially pregnant women, don’t like to go there because nobody will attend to them. They now resort to the services of traditional birth attendants, who are always very handy.”

The director-general of the Primary Health Care Development Agency in the state, Dr Janet Ekpenyong, said she did not know the implementation rate of the BHCPF.

“I heard that the fund arrived late last year. We are yet to see its implementation in the state. The primary health care agency in the state should invite stakeholders to see or know the implementation rate,” she said.

She said the state government had embarked on refurbishment efforts, adding that the primary health care basic fund received from the federal government in April 2022 assisted in the renovation of the centres.

Ekpenyong said, “What we do is to ensure that those we recruit are domiciled in the immediate vicinity of the health centres. Unfortunately, we realised that most of them actually reside in urban centres. We try to bring in retired civil servants, but many remain in the towns. We are trying to contract civil servants back to rural communities with improved incentives to encourage them to stay.”

The state chairman of the NMA, Dr Felix Archibong, said the state had lost over 50 doctors, and now has only 28 in its employ.

While calling for modification of the primary health care system in the state, he said the model the state is still using is the one the late Prof Ransome Kuti, onetime minister of health, put in place, where allied health care officers are used to run primary health services.

“If we had adopted the modified primary medical care where doctors are available, there would have been no need to travel from Obanliku to Calabar for seven hours, for instance. Such cases would have been handled at that level without the hassles of travelling a long distance to look for a doctor,” he said.

Also, the dRPC study on brain drain noted the effects of shortage of health care workers on maternal and child health care, which include the failure of primary health care service delivery policies and programmes as limited workers are moved to urban and tertiary health facilities.

“It also results in increased workload, waiting time for patients, delay in responding to obstetric emergencies, and reduces the quality of family planning service delivery and counselling.

“It is, therefore, impossible to secure child and family health without attention to the recruitment and retention of adequate health professionals,” the research revealed.

The Minister of Health, Dr Osagie Ehanire, who was represented by Professor Sydney Ibeanusi, the Director of Trauma, Emergency and Disaster Response of the ministry, at a recent event on brain drain, said the emigration of trained and highly skilled health workforce was of a great concern as it puts further strain on the already challenged health system.

This investigation was supported by Daily Trust Foundation, in partnership with the development Research and Projects Centre (dRPC)

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.