By: Abubakar Muhammad

The future of children is stifled with the barrier of poverty, old-fashioned cultural beliefs, and an infrastructural crisis in Baita, a small, remote village in Gezawa Local Government Area of Kano State. Despite huge investment in education, Kano, like other states in Nigeria, continues to grapple with a stark gender gap in education. According to the Nigeria Digest of Education Statistics, only 46% of girls are literate in Kano state, as opposed to 73% of boys.

In a typical northern rural community like Baita, the gap would be far wider, with far more barriers standing between female children and education. While policies have been instituted to address these wrongs, the Free and Compulsory Basic and Secondary Education Law, actual implementation of these remains very spotty nationwide.

The impact of such policies is hardly felt in many rural areas like Baita. Programs such as the Gender Responsive Education Sector Plan (GRESP), and the Adolescent Girls Initiative for Learning and Empowerment, (AGILE), have been very effective in improving the educational outlook for girls. These programs, however, are generally not accessible to communities in the most rural and disadvantaged areas.

A Village in Crisis

The village head of Baita, Baita Abdullahi, paints a rather grim picture of the educational landscape.

“We only have three teachers who handle six classrooms. How can three teachers handle the needs of a whole school? The government has abandoned us. Our school desperately needs renovation, and we need more qualified teachers.”

- Kano Gov’t rejects tax reform bills

- ‘Icon of loyalty, compassionate leadership’, Kwankwaso hails Gov Yusuf @62

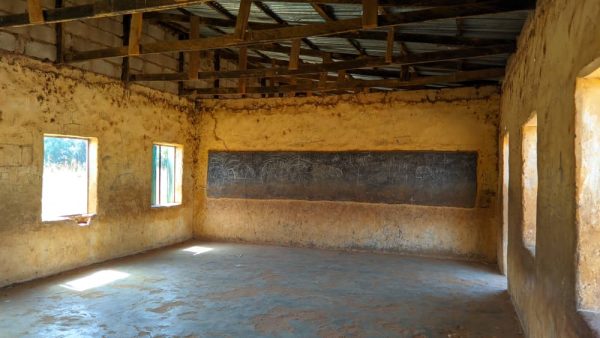

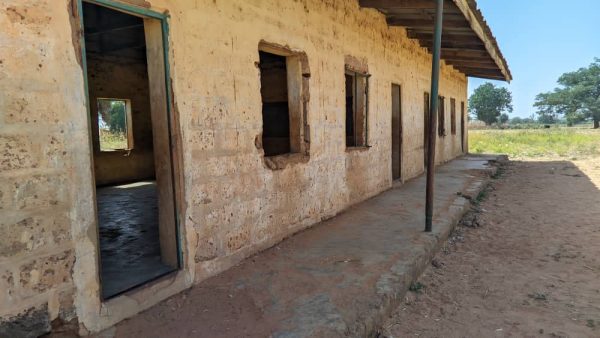

The building itself is dilapidated with cracked walls and a leaking roof; the classrooms are bereft of resources. Sitting on the floor, students struggle to learn in an environment that is both uncomfortable and unsafe.

Most of the parents in Baita hold little value in formal education.

“We are a community founded upon tradition. Many of us do not understand the essence of formal education, and some even think that it would undermine our culture and religion eventually.” Especially among the girls, the belief prevails that they do not need an education once they become old enough to marry or learn household duties.

“The challenge is not just the condition of the school but the perception that education, especially for girls, is of no benefit,” Abdullahi explains. “In most rural areas like ours, modern education is never seen as a worthy investment. After primary school, many send their children to either Islamic schools or stop schooling altogether,” he said.

Added to this, another layer of the challenge is caused by the distance between Baita and the next villages that have better facilities for education.

“The closest secondary school is several kilometers away, and the roads are in bad shape, especially during the rainy season,” Abdullahi said.

“It is dangerous for our girls to walk long distances through rough terrain, and we cannot afford the transportation costs.”

The insecurity coupled with the lack of safe roads usually leaves families with little choice but to opt out of sending their children to school especially the daughters.

Voices from the village

Among children in Baita, sentiment is the same. Sani Ibrahim, a 9-year-old, confesses, “I prefer going to Quranic School because it’s what my parents believe in.”

His friend, 8-year-old Aisha Usman, shares the same view. “My parents don’t want me to attend the primary school because they say it will make me forget our traditions.”

Their parents, Abdullahi Sani and Hauwa Ibrahim, share these fears (The names of the parents are pseudonyms. The individuals requested anonymity out of fear of retaliation.)

“What is the benefit of sending my children to school when they are only going to return and farm?” questions Sani.

“I don’t see any purpose in sending my daughter to school,” adds Hauwa. She will get married at some point and look after her family. Let her concentrate on reading the Quran and learning things which will be very essential for her future.”

Added to this is the factor of distance. “We fear sending our daughters through dangerous paths, especially in the rainy season,” says Hauwa.

“There have been reports of armed bandits and other dangers on the roads, which makes it even more difficult for us to consider sending our children to school.”

All these notwithstanding, GRESP brings some hope. The identification of gender-specific barriers to education can help GRESP address the long-term benefits of formal schooling and the importance of investing in girls’ education for rural communities like Baita.

Poverty, Infrastructural Gaps, and Government Responses

The major impediments to education in Kano remain poverty and lack of access to resources. The Kano government has done fairly well in terms of budgetary allocation to education, but the reality on the ground is quite different. The 2025 budget of Kano allocates 31% to education, up from 29% in 2024.

However, actual budget releases are very slow and inadequate. For instance, while over N13 billion was allocated in the first half of 2024, only N1.1 billion was released, a paltry 8.9% of the sum.

This delay in the release of funds has affected projects that are key to improving access to education, particularly for girls. “We have not received funds for some approved projects since 2023,” says Amina Kasim, the Girls’ Education Coordinator at the Kano Ministry of Education. “Such bottlenecks undermine progress in increasing girls’ education.”

Though financial bottlenecks were presenting challenges for this course, the Kano State government was on top of affairs in other aspects. Gender-sensitive policies formulated include provision for uniforms to pupils at no cost; feeding allowance, and review of Teacher Policy on Girl Child Education.

Former Commissioner of Education Umar Haruna Doguwa has been instrumental in shaping these policies. “We have so far employed 5,643 teachers, mostly women,” says Doguwa.

“Our aim is to close the gender gap in teaching staff and ensure that girls have more female role models in schools.”

Doguwa also faulted past administrations for neglecting the education sector, a factor he says has brought about the current crisis. “So many girls are being left behind due to lack of proper infrastructure and support, but we are bent on reversing this trend,” notes Doguwa. To this effect, the state government has rehabilitated 72 school buses with 57 currently in operation to make transporting girls to school safer. The Conditional Cash Transfer project allows for financial aid to 48,500 girls.

Moving Forward with GRESP

This could transform rural education systems with the GRESP framework, focused on gender-responsive approaches and considering the unique barriers that girls face. It is an indication of how the gap in secondary education access remains stark: whereas Kano has 7,048 primary schools, junior secondary schools drop to 1,148, and senior secondary schools further plummet to 813, with far fewer schools catering specifically to girls.

According to Dr Kabiru Ado Zakirai, Executive Secretary of the Kano State Senior Secondary School Management Board (KSSSMB), Kano State has a total of 813 senior secondary schools, with 450 for boys and only 363 for girls. He added that the rural landscape often has logistical hurdles which limit girls from accessing education.

Zakirai calls for the construction of 92 more boarding schools in Kano’s 23 education zones. He believes that such schools would provide more feasible alternatives for families to send their daughters to school, even though the economic cost of sustaining such schools is a weighty challenge.

Conclusion: A Call for Action

While significant strides have been made in policy formulation and gender-sensitive initiatives, challenges such as poverty, cultural misconceptions, distance, and infrastructural neglect remain major barriers to the educational opportunities of girls in Kano.

Moving forward, the government must ensure the full and timely implementation of policies like GRESP and AGILE. By improving budgetary allocations to transportation options and addressing the logistical challenges in the rural areas, Kano can only do better to ensure each girl gets an opportunity to succeed in school.

Governor Abba Kabir Yusuf reiterated the government’s commitment to reviving the education sector and tackling the challenges facing it head-on. “We have sent six draft policies, including the Kano Education Law, 2024, and the Kano Teacher Development Policy,” said Yusuf. “These policies will make sure that every girl in Kano has an opportunity to succeed.”

It is high time for concerted efforts to close the educational access gap and provide the required support to girls in Kano’s classrooms.

See pictures below:

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.