Earlier this month, the Minister of State for Education, Professor Suwaiba Sa’idu Ahmad, was reported to have said that almajirai are not out-of-school children. I have since read numerous news reports on this and watched a clip of her full interview with Arise TV.

The minister’s point, as I understand it, is that the almajirai are in an alternative educational system, however informal this system might be, with their own teachers, curricula and learning activities. Therefore, almajirai in tsangaya schools cannot be included among the total for out-of-school children, since they are in school and are having some education. In order to meet the demands of Nigeria’s constitutional principles and federal statutes on basic education, however, the government will inject elements of the Universal Basic Education (UBE) like reading, writing, arithmetic and some vocational skills into the tsangaya system.

We should give credit to the Tinubu government, and Jonathan’s before it, for even thinking about the almajirai, and going further to devise a policy for them as contained in the “Education for Renewed Hope” policy-document and the establishment of the National Commission for Almajiri and Out-of-School Children Education. This credit is due because President Buhari spent eight years in the same office, and scarcely said or did anything about it. Still, this policy appears to be seeking to wish away a serious policy challenge in Nigeria with a definitional or semantic argument.

Almajirai are estimated to number around 9.5 million or about two-thirds of Nigeria’s conservative figure of 15 million out-of-school children. By the minister’s proposal, therefore, we will overnight reduce the number of our out-of-school children from 15 million to five million with just a simple redefinition of terms and some cosmetic reforms. This is my problem with it all. I find this not only unacceptable and inadvisable, but also dangerous because almajirai are out-of-school children, however one defines “almajiri” or “out of school”.

- Hardship: ‘70 million Nigerians to get N75,000 each’

- Niger tanker explosion: 86 buried, 43 hospitalised, others missing

According to UNESCO, a global authority on the subject, out-of-school children are “children and young people in the official age range for the given level of education who are not enrolled in pre-primary, primary, secondary or higher levels of education”. That is, the formal structures of learning and schools devised by the national or subnational governments of different countries.

In Nigeria, this practically means only the system of education that leads to the attainment of School Leaving Certificate, Junior Secondary School Certificate, Senior Secondary School Certificate, etc., through such exams as the Common Entrance, WAEC, NECO, JAMB, etc. Any Nigerian child aged 6–17 who has never attended or completed these levels of education is simply out of school. At the moment, the tsangaya system, and the education young almajirai receive from it all would NOT lead to Common Entrance, WAEC or beyond, and are therefore out of school.

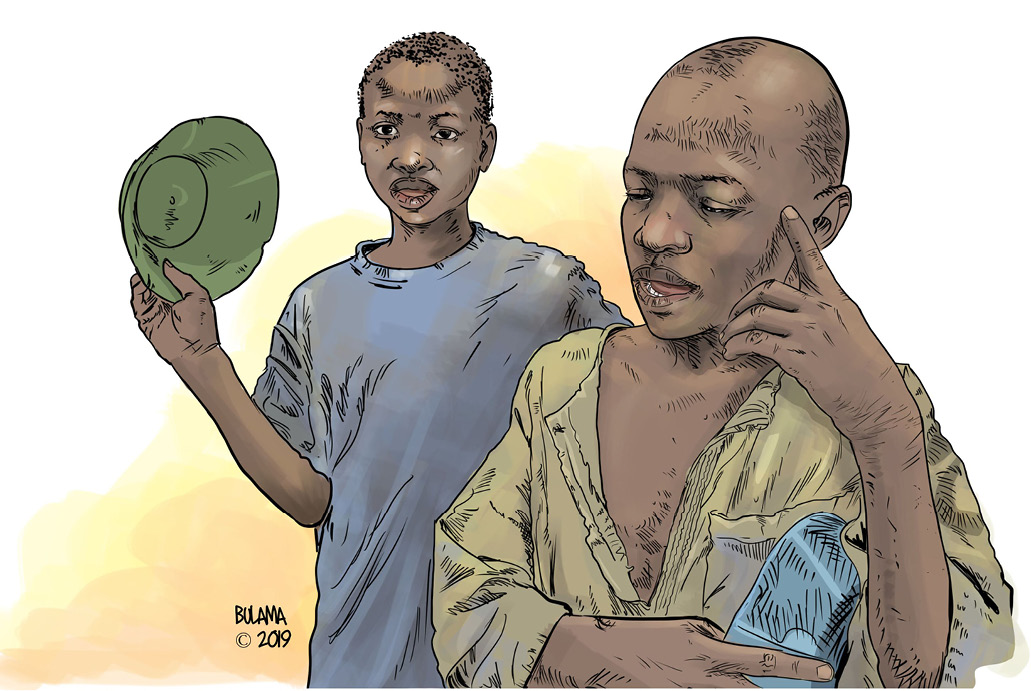

You may have seen that iconic image of a group of almajirai standing outside a formal school, their begging bowls in hands, watching admiringly as other kids their age receive an education in a system from which they have been excluded. That image tells a story of inequality, exclusion and lack of access. But it is also a blunt statement that the two forms of education are not the same, and that the one cannot be a substitute for the other, even though each has its value.

Moreover, the almajiri/tsangaya system currently in operation throughout northern Nigeria is the same as we knew it because the baby has long been thrown away with the bathwater. In the original almajiri system, food supplied by parents, farm work, and other vocations like retail trading and teaching were all an essential part of the process as students and their education grew over many years.

In today’s tsangaya schools, however, children—some barely five years old—are condemned to begging for food in the streets and exposed to other kinds of threats to their lives and limbs at all times. This is not an alternative education system but a form of social violence, that is, a structural organisation of child abuse, whatever else of value we may find in it.

Furthermore, basic education is more than just about foundational literacy and numeracy. It is also about promoting a uniform national culture, however contested it may be. Although Nigerian governments since 1960 have not been sufficiently skilled to use the formal education system to build a uniform national culture throughout the country, the potential remains there. And as things stand, the exclusion of the almajirai from the formal education system, and hence from the uniform cultural system, amounts to inflicting on them an inequality of the highest proportions that cannot be remedied by the proposed reforms, not to mention the obvious dangers of nation-building.

Equally important, perhaps even more so, is the fact that basic education is a tool for equitable distribution of what sociologists call “life chances”, that is, the social and economic opportunities available to people for improving their quality of life. In his Development as Freedom (1999), the Indian economist and Nobel Laureate, Amartya Sen, particularly stresses the importance of education to the overall capability approach to development he argued throughout that book (this is the original idea of the metrics our National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) now uses to measure something called “multi-dimensional poverty”). But we can see more practical illustrations of this throughout northern Nigeria in the significant differences in life outcomes that are manifest, on average, between those of us who had both the “Western education”, to put it bluntly, in formal schools and those who had only the tsangaya education. Even among northern Muslim religious leaders, this difference is clear and constant, and has serious impact on people’s life chances.

There is no substitute for having the opportunity to become a medical doctor, a lawyer, an engineer, bureaucrat, a newspaper columnist, or for that matter a ‘Western educated” Muslim religious leader, even if you don’t end up becoming any of these things as a matter of choice or fate. The crucial thing is to have the same opportunity as everyone else. All public policies, the Nigerian government must teach itself to learn, are underpinned by some political philosophies, whether we are aware of it or not.

It should be clear by now where I am going with all this. All of us northerners—leaders and the led alike—must tell ourselves the brutal truth: we need to abolish the current almajiri system and build something new and more purposeful in its place. There are two billion Muslims in the world, and in nowhere else but northern Nigeria and its environs does this practice persist. And we can do this even without the federal government, although its support can come in handy.

Throughout Nigeria, there have emerged over the past 30 years new models of education that combine Islamic and Western education into one single unified system based on the same formal structures everybody else in the country receives. These schools are everywhere across the country, and their students go on to attend university or other tertiary institutions, just like everybody else everywhere. For now, they are mostly private or charity initiatives. But with the right approach and clarity of purpose, this model can work within the existing public primary and secondary education systems in most northern states in ways that will not harm or exclude anyone else.

It will also be cheaper and more feasible because the infrastructural and logistical support needed to make the existing tsangaya schools fit for integrating the Universal Basic Education in the current proposals would even be more daunting. Whatever we do, the challenge of the moment is not to dance with language around the almajiri system but to transform it by first abolishing it.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.