This year has not only seen the release of critically acclaimed works by writers from across continent, but it has also been filled with wins and international recognition.

This year has not only seen the release of critically acclaimed works by writers from across the continent; it has also been filled with wins and international recognition.

- I escaped kidnaping by providence – Commissioner

- INVESTIGATION: 5 Years On, FG’s Whistleblowing Policy Falters

From scooping a string of important awards to releasing a number of critically acclaimed books, writers from across Africa took the literary world by storm in 2021.

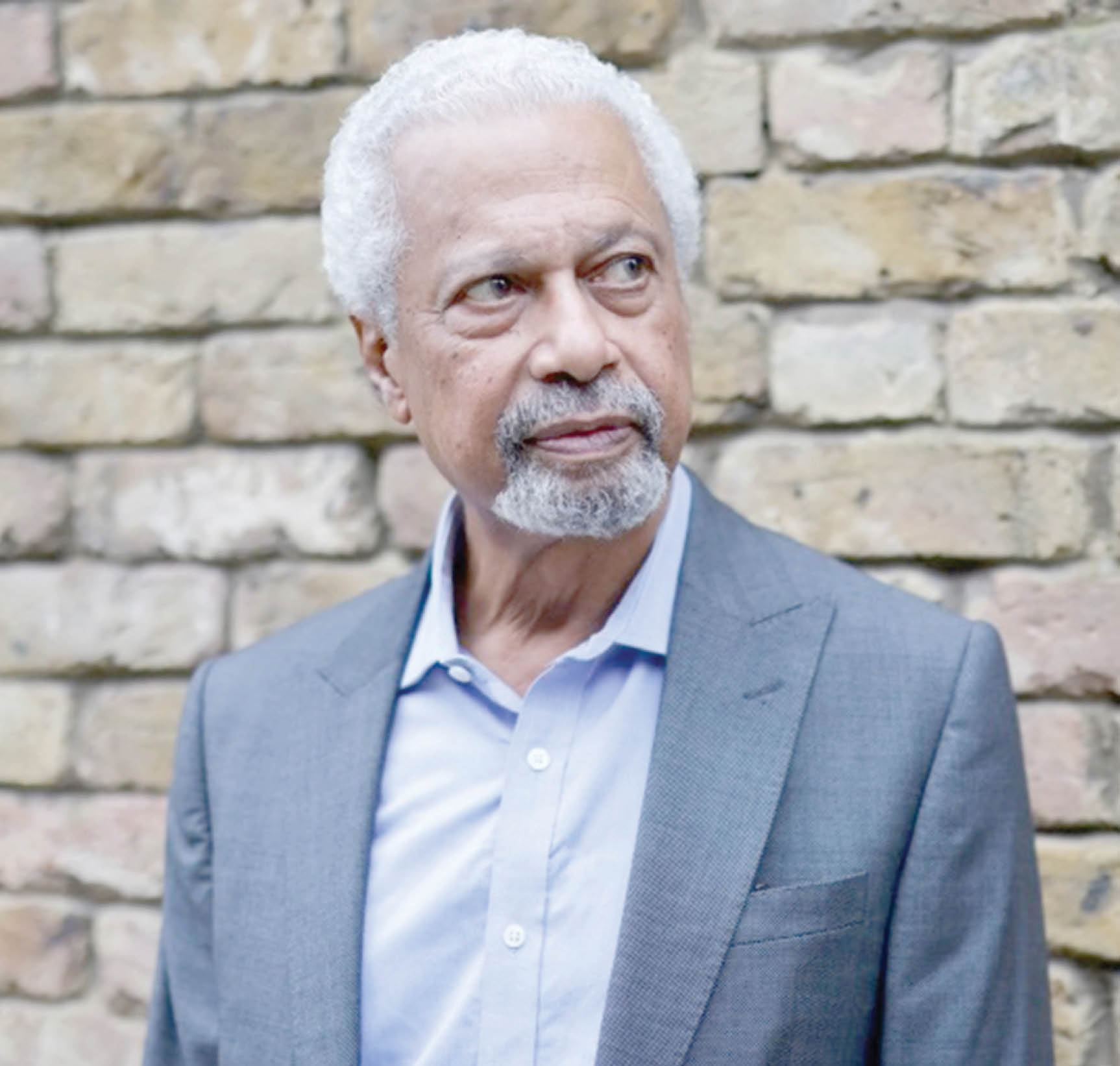

The crowning moment came on October 7, when Zanzibar-born Abdulrazak Gurnah was named the winner of this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature. Weeks later, South African author, Damon Galgut, won the prestigious Booker Prize for his novel, “The Promise”, while British-Somali writer, Nadifa Mohammed’s “The Fortune Men”, was on the shortlist.

African writers who penned novels in French also saw big success; with Senegalese novelist, Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, winning one of France’ oldest and most illustrious literary prizes, the Prix Goncourt, for “La Plus Secrète Mémoire des Hommes” (The Most Secret Memory of Men).

The novel also saw Sarr win this year’s Hennesy Book Award and the Transfuge Award for Best French Novel.

Fellow Senegalese author, Boubacar Boris Diop, who is also an essayist and journalist, was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, a biennial award sponsored by the University of Oklahoma and World Literature Today since 1970.

Completing the trio of successes for Senegal, French-Senegalese novelist, David Diop, won the International Booker Prize for translated fiction for “At Night All Blood Is Black”.

This was also the year when Paulina Chiziane, often referred to as Mozambique’s first woman novelist, was awarded the 2021 Prémio Camões, widely considered the most prestigious prize in the Portuguese literary world.

Meanwhile, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, a United Kingdom-based Ugandan novelist, was awarded the 2021 Jhalak Prize for her novel, “The First Woman”.

‘More opportunities’

Bhakti Shringarpure, the founder of Radical Books Collective, said the prizes “amplify” the literary scene of various countries on the continent and “generate legitimacy”.

“It certainly means more opportunities for African writers with publishers, agents and editors, and an opportunity to be heard. And of course, gaining more mainstream attention means encountering more African literature in bookstores,” said Shringarpure, who is also an associate Professor of English and Gender Studies at the University of Connecticut.

While there is little doubt the accolades have cemented 2021 as an exemplary year for literature from across the continent, what kind of effect do the writers themselves think these awards have?

Tsitsi Dangarembga, a distinguished Zimbabwean novelist, playwright and filmmaker who earlier this year won the 2021 PEN Pinter Prize and the Peace Prize of the German book, “Trade”, said that while the prizes helped shine a light on her work for a finite period of time, she was unsure how much of this translated into any form of enduring outcome.

“In five years or so, I would like to look back and say that these awards were the beginning of a period in my life where my work was much more generative in terms of my achieving my goals,” said Dangarembga, who is also an activist and social justice advocate.

While she hopes her creative work helps others to analyse the world, Dangarembga said she would also like “the kind of success that increases my influence so that I can impact events in Zimbabwe and on the continent more through my work and social analysis.”

‘Not bending to Western demands’

While writers from Africa are no strangers to award recognition, which has led to literature from across the continent and its diaspora increasingly finding a place on the global stage, a multitude of factors led to the kinds of success seen this year.

Shringrarpure highlighted the fact that writers such as Gurnah, Diop and Dangarembga are uncompromising in their political conviction and engage literature to give us “complex, nuanced, honest and beautiful portraits of African lives and experiences.”

She said, “(They) have never bended to the demands of Western publishing and have consistently refused to accommodate themes and styles that suit mainstream readerships.”

This almost disregard of the Western gaze has led to writers and publishers bringing to audiences a diverse range of stories from across the continent. For example, Sarr’s “La Plus Secrète Mémoire des Hommes” tells the story of a young Senegalese writer in France, while David Diop’s “At Night All Blood Is Black”, is a harrowing yet necessary read about a Senegalese soldier fighting in World War I.

Niki Igbaroola, the Talent and Audience Development Manager at Cassava Republic Press, a publishing house that publishes works by African writers, said that while the growing bearing of the “Black Lives Matter” movement on the publishing industry could be ignored, there had also been an “organic rise in the global consumption of African art.”

“The problem has never been whether or not the work exists, but if the work is being given visibility,” said Igbaroola, crediting the “rogue” nature of social media for causing a shift in the “voices of influence” and affording greater power to readers “in dictating consumer habits”.

Indeed, the power of social media, coupled with the existence of publishing houses focused on African literature and what Shringarpure described as “the intensity with which Africans on the continent produce literary and publishing structures online” have all played their part in literature from Africa being widely recognised.

“So far, and ironically, African literature tends to be entirely constructed around single authors,” said Shingrarpure, citing award-winning Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie.

“It is important that we accidentally stumble upon a variety of African literature from different countries, written in different genres in our daily lives whether we’re in the West or elsewhere.”

Meanwhile, Igbaroola said that while it is hoped that more African writers gain recognition in the form of prestigious awards earlier in their careers, she stressed that such accolades do not necessarily translate to a larger audience.

“While prizes can boost sales, more often their biggest value lies in prestige and they are not always an indicator that these authors are being widely read, or their books adequately distributed, both on the continent and abroad.

“It is important not to lose sight of this, even as we celebrate these successes,” she added.

Culled from Al Jazeera

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.