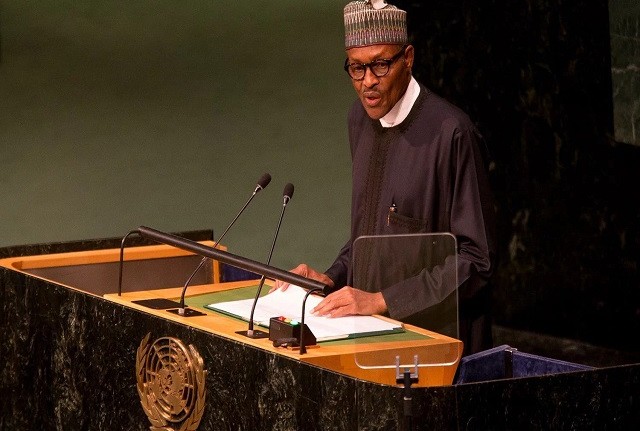

Addressing the second African Sub-Sovereign Governments Network (AFSNET) Conference in Abuja on Friday last week, President Muhammadu Buhari reiterated the need for more effective regional economic integration among African countries.

“As leaders”, the President said to his counterparts on the continent, “we must all be concerned that we are not trading enough amongst ourselves. It is a bitter reality that intra-regional trade still accounts for a very tiny fraction of total trade in Africa”.

Nigeria@62: Africa’s giant of yesterday, today and tomorrow

Nigeria 2023 polls: Here come the campaigns

President Buhari could not have spoken at a more crucial moment for Africa. Amid global economic turmoil of the past few years, African economies are in dire straits, as developments in three key economic areas amply illustrate in recent months. The first is rising inflation in many African countries, as economies witness steep rises in the prices of goods and services, particularly food and fuel. While the overall inflation rate in Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to grow to a record high of 12.2%, it is significantly higher in many countries than the continental average. In Ethiopia and Ghana, for example, the inflation rate is 34.5% and 33.9%, respectively, and hovers above 20% in three African countries: Angola (23.9%), Nigeria (20.5%) and Rwanda (20.4%), according to a recent and perceptive article by this newspaper.

Food inflation on the continent, in particular, is even worse. Staple food prices in sub-Saharan Africa have surged by almost 24% in 2020-22, the most since the 2008 global financial crisis, according to a release by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) only last week. Since Africa imports many of its top staple foods like wheat, palm oil and rice, global factors have contributed to the rising food inflation on the continent, the IMF said. But the report also makes clear that local factors—domestic supply chain disruptions, local currency depreciations, and higher fertilizer and input costs—have also contributed. Cassava and maize are locally produced in Nigeria, but their prices have doubled this year, and in Ghana, cassava prices have increased by 78%.

Local African countries have also taken a hit, badly. No one knows what the Ghanian Cedi is worth anymore; and in Nigeria, the Naira has reached unprecedented levels of depreciation in the international exchange markets, while the CFA, used in 14 African countries but linked to the European single currency at a fixed rate, has plummeted in value resulting directly from the decline of the Euro against the dollar.

The result of all these is an increasingly grim regional economic outlook and worsening poverty situation on the continent. According to the 2022 African Economic Outlook, released in May this year by the African Development Bank (AfDB), while Africa’s gross domestic product grew by an estimated 6.9% in 2021, it is expected to” decelerate to 4.1% in 2022, and remain stuck there in 2023, because of the lingering pandemic and inflationary pressures caused by the Russia-Ukraine war”. The report further noted that while around 30 million people in Africa were pushed into extreme poverty in 2021 and about 22 million jobs were lost in the same year because of the pandemic, this trend is expected to continue, with an additional 2.1 million Africans estimated to slide into extreme poverty in 2023.

Daily Trust believes that while these stark figures are dauting enough for African economies, the bigger problem is a lack of concerted efforts at real economic integration at regional and sub-regional levels. While African leaders are happy to be massed in a bus in Britian’s capital for Queen Elizabeth II’s state funeral or to be lodged at expensive hotels in New York for the UN General Assembly last month, millions of Africans at home are yet to see similar levels of enthusiasm for systematically approaching and solving collective economic problems on the continent.

Africa has always been the most vulnerable to global economic shocks that have grown more frequent and severe in recent years. This is mainly due to a telling lack of collective strength on the global economic scene. African countries trade more individually with the rest of the world than they do with each other at home. As a 2019 report by the Brookings Institution shows, intra-regional trade in Africa stood at 17% in 2018, a paltry figure compared to 69% in Europe and 59% in Asia. Yet, regional and sub-regional initiatives towards Africa’s regional economic integration have scarcely gone beyond news headlines and high-sounding rhetoric by African leaders.

Debates about an African Central Bank, the Afro as a single currency on the continental level, and even the Eco at sub-regional level have not materialized. And when it was conceived in 2018, the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AfCFTA), which commits countries to remove tariffs on 90 percent of goods, progressively liberalize trade in services, and address a host of other non-tariff barriers, it was lauded as a new chapter in Africa’s regional integration that will make Africa the largest free trade area in the world by creating a single African market of over a billion consumers with a total GDP of over $3 trillion.

Yet, it remains no more than a distant dream, as do complementary initiatives like the Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, Right to Residence and Right to Establishment, and the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM).

But as the current global economic crises deepen Africa’s vulnerability to external shocks, a renewed commitment to regional economic integration African leaders, governments, regional bodies and businesses is required. A good place to start by all stakeholders is to demonstrate a political will that goes beyond talk.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.