One of the most delicate debates I’ve followed in Nigeria, without subscribing to a definite position, is the necessity or otherwise of state police.

The centralisation of the country’s security architecture has created a Federal Government that’s so overwhelmed, the yearnings for reforms feel like a cruel joke.

Banditry: Police deploy 877 personnel to Zamfara communities

Troops rescue 22 kidnapped victims in Zamfara, Katsina

Abuja’s monopoly in the law-enforcement business has played out, and quite frequently, as clashes of interests between persons with positions or favours at the centre and state Governors.

But the imagination of what a vindictive Governor would also do to the political opposition, if in control of a state-owned Police, has left many Nigerians holding back their solidarity with state governments.

Earlier this week, the Premium Times online newspaper brought to the fore, again, the ugliness of this perennial power schism, this time in Zamfara state: ‘In the space of ten days, two chieftains of the All Progressives Congress (APC) in Zamfara State were arrested by the state’s police command over allegations of connivance to disrupt peace in the state through alleged use of bandits,’ the report says.

But that’s not the subject of my concern.

The report further adds, “But in both instances, higher authorities of the police directed the release of the suspects citing ‘orders from above.”’

The freed politicians, Abdulmalik Bungudu and Abu Dan-Tabawa, were arrested at different times, according to the report, for “mobilising thugs and armed bandits to terrorise residents of his local government” and convening a meeting attended by the alleged killer Fulani herdsmen, respectively.

In both cases, the Police were handed the ignominy of setting free persons they toiled to net in.

This unusual power play has again reawakened the nation to revisit the nominal power of state Governors as Chief Security Officers of their jurisdictions, against the Police institution tele-guided by the authorities in Abuja.

It’s also brought back the memory of such manifestations of partisan policing in previous governments.

The PDP-led government of then-President Goodluck Jonathan deployed the Police in the build-up to the 2015 elections to disarm perceived antagonists.

The famous G7 Governors—a group of 7 rebellious PDP Governors against the re-election bid of President Jonathan—were subjected to an endless nightmare that the Police even invaded the Kano State Governor’s Lodge in Abuja to disrupt their meeting.

The eruption of this face-off was the hounding of Governor Rotimi Amaechi of Rivers State, a member of G7 and one of the five to eventually leave the then ruling party, by Police Commissioner Joseph Mbu, who was activating Abuja’s partisan agenda.

What’s happening in Zamfara, however, isn’t playing out in the exact pattern.

It’s a contest for, and of, power and relevance set in motion by the political storm that changed the state’s power equation last year.

Both the holders of the executive and legislative offices in Gusau thrive on the resistance of former Governor AbdulAziz Yari-led APC camp who lost their offices to the PDP after the Supreme Court ruled last year that the APC, having failed to conduct a valid primary election for the 2019 general elections also had no candidates—and the PDP, who were the first runners-up took over the nullified Governorship, National Assembly and State Assembly seats.

“It’s a miscarriage of justice,” declared a pro-Yari partisan in a viral video of what’s a protest over the arrests of their members by the police.

“The protest leader had been identified as Sunusi Salisu Mai Bakin Zuma, and a loyalist of Yari.

“The effrontery displayed by Sunusi Mai Bakin Zuma in that address to the press is reminiscent of the gusto by PDP members of Rivers State House of Assembly loyal to Madam Patience Jonathan—you could feel the boast that comes with having the backing of a superior power.

“He not only censured the Judiciary and assaulted the police commissioner in Zamfara, Usman Nagogo, but he also threatened, to the cheering of the crowd behind the cameras, to “take the law into our own hands.”

Since 1999, Zamfara state has been a laboratory of calculated mischief and grand deceits, as local politicians stoke mass sentiments, and usually selective and superficial application of Islamic principles, to escape public scrutiny and accountability to the masses.

The pioneer in this game of throne is Governor Ahmed Yerima, the first elected in the fourth republic, who hid behind Sharia implementation politics to pursue his agenda.

The most memorable outcome of his stewardship, unfortunately, is his long-running corruption case with the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC), and an utterly impoverished state.

Yari amplified this tragedy of leadership by marking out—if not wasting—an uneventful eight years.

When faced by the failure of his leadership, during the 2017 fatal outbreak of Type C Cerebrospinal Meningitis in the state, he propounded a strange thesis: “There is no way fornication will be so rampant and God will not send a disease that cannot be cured”.

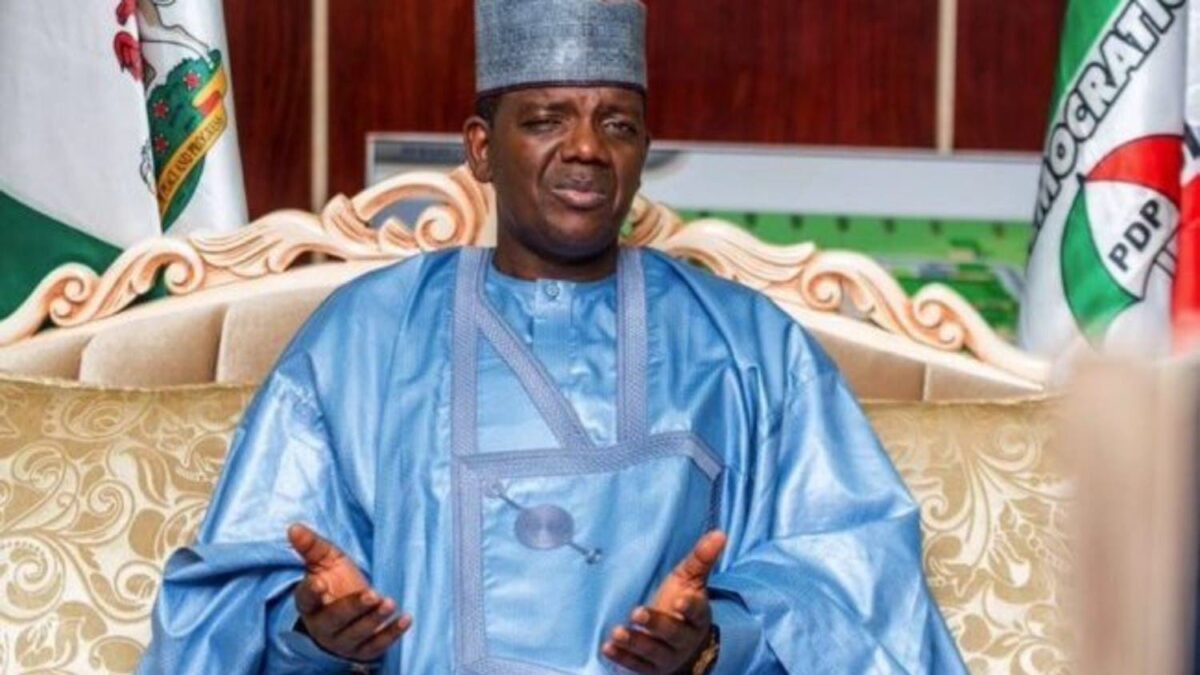

Zamfara was this subject of public relations disaster when Governor Bello Matawalle took over last year.

The interest in Matawalle was instigated by the anti-intellectual posturing of his predecessor and his identification of social media as a place of fair judgment.

His Twitter account became a diary of his sincerity in finding a solution for the instability and economic drought in the extensively misgoverned state.

In his early months in office, he shared consistent updates of his trips to “ungoverned” areas where kidnapping and banditry had disrupted life, a task expected from his predecessor who, at a point, could’ve even passed for the Mayor of Abuja because of his absence in Gusau and inglorious dabbling in national politics.

And so, when Matawalle eventually announced an amnesty programme to fast-track his peace-building initiatives, after his well-publicised venturing into the hinterlands and the dens of terrors that had made Zamfara the capital of banditry in the country, his followers understood despite the reservations from certain quarters.

But Matawalle’s appeal rose late last year with his shocking removal of the Emir of Maru, Abubakar Cika, and the district head of Kanoma, Lawal Ahmad, for allegedly aiding bandits.

It’s a politically suicidal move in a state where Islam and feudalism had been misapplied in the production of the fundamentally parasitic and unsympathetic ruling elite.

I had not followed much of his activities in recent months until I chanced upon the Premium Times report of high-powered interferences with the arrests of politicians abetting bandits and stoking violence in the state.

But, unlike what we experienced in River states in those crazy months before the 2015 elections, the Police authorities do not appear to be at war with the governor.

They seem to be playing to the hands greater than them, politically.

The state Police Commissioner, Usman Nagogo, had even told the Press they moved to arrest saboteurs after discovering they were meeting with some leaders of repentant bandits pardoned in the amnesty programme to incentivise them to take up arms.

The origin of these orders undermining Governor Matawalle’s authority is a partisan power play that must be neutralised before it evolves into irreparable damage, and reverses the efforts already in place to build peace in the state.

The sustained loyalty of the Police commissioner and his superiors in this chaos is also a subject of concern.

Nigeria’s unipolar policing means that the men in uniform often, even if out of the will, answer to their paymaster in Abuja or persons close the powers at the Villa, as is alleged in this case.

This resort to self-help through pulling powerful strings is a fire we must rush to stop before it blows up in our faces.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.