Carrying 10 to 20 tubers of yam on their heads, Jos women yam hawkers walk as far as 10 kilometres, mostly under the intense scorching sun and sometimes drenched in the rain with a baby strapped to their backs. It is the life they’ve always known, but now wish better for their daughters. Daily Trust Sunday looks at the hard life of Plateau’s women yam hawkers, the nature of their trade and how it traps them in a revolving circle of debt.

In her 70 years, Lami Mayangwa still carries huge tubers of yam and walks the distance. Life has not been kind to the septuagenarian. Her feet are covered in blisters which make it thorny to walk. But she says the blisters and the backache she’s managed for over 30 years are signs of the hard life she still lives. “My back hurts all the time, my chest and shoulders also. My feet hurt like fire and to walk is now becoming problematic,” she said.

For Lami’s daughter, Laraba; a mother of six children, this is the life she was born into. “It is normal,” she said and explained that she had joined the trade as a little girl who followed her mother about with a little tray of yams. It is a trade she now struggles to transfer to her two daughters; Diana and Joy.

Yam hawking, Lami said, is a trade four generations of women in her family have taken to. Her late mother had sold rice before venturing into yam hawking in the 1940s. Now, Lami’s 42-year-old daughter, Laraba, and two of her female grandchildren have joined the venture, walking as far as 10 kilometres daily, around Jos city to hawk the staple.

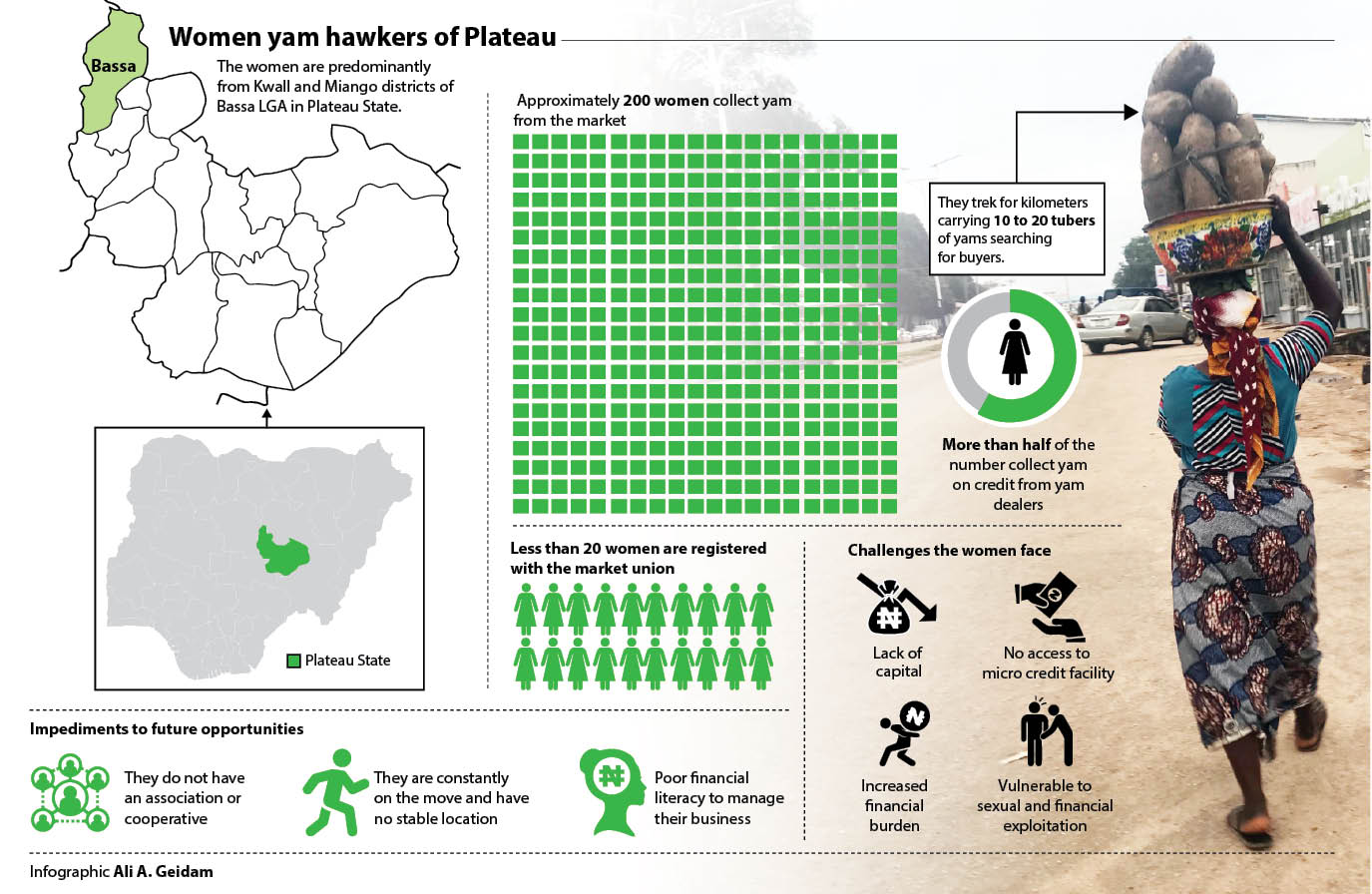

The sight of the women hawking tubers of yam is one that has become normal in Jos and surrounding environs. Most of them are of the Irigwe extraction, indigenous to Miango and Kwall districts of Bassa local government area in Plateau State. There is no record of when the Irigwe women ventured into yam hawking, but oral records from older generations like Lami and yam dealers in the state say it is a trade they’ve been known for since as far back as the 1940s.

Amongst a group of cheerful young housewives who hawk yam at Chobe Junction in Jos, our correspondent met two 25-year-olds; an agile Blessing Audu in a grey Tee Shirt and a subtle Nancy John, clad in a red and black spotted Ankara. The women use the popular spot at Chobe as a station to store their yam tubers and take a few minutes rest before they continue the day’s walk. Both Nancy and Blessing had married by the time they turned 18 and immediately joined the trade to make ends meet. Blessing has four children; three of them girls and now fears that they may end up taking after her. “I want a better life for them, we want to see women from our community one day become doctors, lawyers and even ministers,” she said.

Esther Sunday, 37, has six children; all girls. Already she says, two of the girls are learning the ropes of yam hawking and most times accompany her to the city from their village in Kwall. “We wish our children would not have to venture into this hard life, but there is not much that we can do,” she told Daily Trust in Hausa. Sitting on a small wooden stool and leaning across this reporter while other young hawkers nodded in encouragement, Esther continued; “we make some little profit from the yam we sell but the money comes and goes because there are a lot of responsibilities. We take up most of the financial burden at home.”

Inside Yan Doya market

On a typical October morning, the Yan Doya market is jam-packed with yam suppliers, dealers, retailers and hundreds of labourers. The muddy and slippery condition of the market during the rainy season poses a threat to both buyers and sellers. Nevertheless, constantly seen in the market, navigating their way in between mounds of yams are the women yam hawkers who move from one dealer to the next to bargain a good price. Directly situated behind the popular Jos Terminus market, Yan Doya is always a hive of activities. The women yam hawkers mostly collect yams in mounds from dealers, then store them in specific locations where they fetch between 10 and 20 tubers for the day’s trade.

Salisu Ibrahim NaYelwa is a supplier and a dealer of yams. The 62-year-old ventured into the business in 1972 and said there are over 40 varieties of yam brought into the market from parts of the state’s southern senatorial district as well as other states such as Taraba and Kaduna.

Yam is one of the major staple crops produced in Plateau State. The tubers are produced in Shendam, Qua’an Pan and Langtang South local government areas in large quantity and a small portion among the Irigwe of Bassa. Other varieties are brought into the market from mostly Kaduna and Taraba states.

A mound of yam, which is called Kwarya in Hausa, contains 100 tubers. At the time our correspondent visited the market, NaYelwa said the Ma’anpa yam; brought from parts of southern Kaduna, is in season. He, however, stated that because the Irigwe people share a border with the southern Kaduna community, they were regarded as pioneer traders of the Ma’anpa into Jos. At the time of the visit, the Ma’anpa yams were arranged in mounds with a single tuber costing between N50.00 to N100.00 depending on the size.

With dozens of labourers; both young and the elderly sighted loading and offloading yams in the market, Maigari Lamido, chairman of the market union, said Yan Doya was established about 55 years ago and put the number of registered and unregistered members at 2,000.

“As much as N10m worth of yam is sold daily in this market,” he said, adding that; “we don’t have a clear number of the women yam hawkers who access the yams on credit but they are at least 200 women. But those who are registered are less than 20,” he said.

To become a member of the market union, our correspondent learnt that each woman is expected to pay a registration and membership fee of N500. But Lamido explained that membership has become a task the women yam hawkers continue to view with some reluctance.

Breadwinners and proud

“Life is hard, we walk for hours, not necessarily because we have a specific destination but in the hope that someone could spot us and call us to buy the yams,” said Blessing Audu who compared to Lami and Laraba is merely a cub yam hawker. She, however, confessed that there were many times when she’d walk the whole day without selling a single tuber of yam. “Sometimes, it is simply a matter of luck,” she said.

Like many low-income earners that have become breadwinners, the yam hawkers take larger responsibilities at homes. As breadwinners, the women said they shoulder feeding, education and the health needs of their families. Laraba, who is popularly called Maman Ishaku, explained thus: “Most of our men are irrigation farmers and sometimes a man could farm and bring it to the house to honour his responsibilities, but that ends there. The woman must shoulder the responsibilities of buying the ingredients to cook the food or soup. But then again, there are times when the man leaves everything to the woman.”

Because the women carry the yam on their heads in search of buyers, the trade is considered a woman’s venture and culturally forbidden for men. Not many could explain why this is so, except that it is a cultural belief that predates them.

“Men do not sell yam, our culture does not allow a man to carry anything on his head, we were brought up to see our mothers hawk yams, but we have never seen a man from our tribe carrying yam on his head, it is not our way,” said Esther Sunday. Speaking with pride, she noted that she doesn’t mind being a breadwinner because culturally, women were designated ‘helpers’ of their husbands. “Our culture expects that whoever has the resources should take up the family responsibilities, our men do not earn much because they are farmers and they make money seasonally. We, however, hawk daily and are likely to return home with some money daily,” she said.

Giving a better perspective on the resilience of the Irigwe women, the member representing Rukuba/Irigwe in the Plateau State House of Assembly, Hon. Avia Musa Agah, said culturally, the Irigwe women are hard-working and stressed that even when the man is buoyant enough, Irigwe women will feel the need to independently find a source of money for the betterment of the home.

Giving a better perspective on the resilience of the Irigwe women, the member representing Rukuba/Irigwe in the Plateau State House of Assembly, Hon. Avia Musa Agah, said culturally, the Irigwe women are hard-working and stressed that even when the man is buoyant enough, Irigwe women will feel the need to independently find a source of money for the betterment of the home.

But despite their prowess to assist their men financially, the women noted that the increasing domestic burden entraps them and their female daughters in a circle of poverty. For most of them, their daughters can only go as far as basic education. Advancing to senior secondary or tertiary education often comes with inherent challenges which Esther says is due to high domestic demands and scarce resources. “We try to make sure the children attend school up to secondary school level, that is as far as we can go,” she stated.

Trapped in a loop of debt

She walked swiftly like a woman in distress, carrying 10 tubers of yam in a basin. A stream of sweat cascades from her forehead down to her chin. The back of her ‘george’ fabric top looks drenched from the heat that serves as a consequence of the afternoon scorching sun. But that seemed the least of her worries. If hard work and resilience could determine success, then Susan David, who walks for many kilometres with tubers of yam on her head said she would have been rich. The mother of eight children only agreed to speak with our correspondent on the promise that her identity would be concealed. “I have been doing this for more than 20 years,” she told this reporter, adding that; “yet I don’t have much to show for it, I don’t even have capital because the little profit goes into feeding and other family needs.”

Susan said she pairs with a friend to collect a mound of yam from dealers at Yan Doya at least twice a month and pays backs as soon as they sell the yams. “That means we have to split the profit into two. It’s a life of constant debt,” she said with a hiss.

The women yam hawkers may appear strong, determined and sometimes very cheerful, but a majority of them barely make enough to address their basic family needs. With no capital to sustain their businesses, most women pair themselves in twos and threes to obtain a mound of yam on credit. The price of a mound, our correspondent gathered depends on the size of each yam tuber which could go for N50, N100 or more. There are times a mound of yam could sell for as low as N8,000 but there are also times they could sell as high as N38,000, N50,000 or slightly above.

Maman Ishaku told our correspondent that despite all the anguish that goes into getting the yam on credit, the profit margin is not as one could expect. From a mound of yam, she said, a profit of between N1,500 to N3,000 is usually made depending on how early one can sell off the commodity and ask for more. Chairman of the market said though most of the women are not registered with the market union, they have earned the trust of yam dealers which is why they give them yams on credit.

“One thing is certain; the Irigwe women are trustworthy because we barely have cases of any of them defaulting. But there are precautions we take to make sure they payback. We ensure that any woman who wants to access yam on credit must come with another woman who is known to us to serve as her guarantor,” he said.

Between them, Lami Mayangwa and her daughter Laraba have 70 years of business experience yet they are unable to raise enough capital to purchase the yams they hawk. Instead, they rely on decades of trust they have built with dealers to collect the staple on credit. For Laraba, the profit doesn’t come easy as it sometimes takes days or weeks to sell a mound. “It all depends on how hard you work or how good the market is or sometimes, you’ll need luck.” This is because there are also circumstances where customers could collect the yams on credit and ask the hawkers to return on specific dates for their money.

Susan David explained that; “because we are desperate to empty the storage, we give out the yams on credit, but there are times that the customers will drag payment for weeks or even months.”

Ignored by social investment schemes

In July, Blessing Audu said she came across a cooperative that promised her and others access to a N20,000 loan with an interest of 10 per cent and payable within 11 weeks. Blessing said the cooperative had asked her to pay N5,000 registration fees to be eligible for the loan, which she did. Three months later, the mother of four told Daily Trust on Sunday that she and four others who paid registration fee were still hopeful. “They said we would pay them N2,000 each week and at the end of 11 weeks pay N22 000 including interest of N2,000. We have paid the N5,000 registration fee, but they have not disbursed the loan yet,” she said.

Unlike Blessing, Esther and Laraba said they have not joined any of such cooperative for fear that they may be scammed. “If we were to get a loan, it will go a long way in boosting our business, but there are many people who are also ready to prey on the little profit we make so we have to be careful,” said Esther.

For lack of an association or cooperatives, the women have been unable to benefit from any form of financial assistance and so are susceptible to financial exploitation. They, however, lamented that they have never benefited from any loan initiative from either the federal or state governments. “No one remembers us when it comes to money, but we will be happy if they will consider us,” said Laraba.

With the introduction of the Federal Government’s Market Moni and Trader Moni schemes in Plateau State, the yam hawkers joked that they must have been “omitted” from the programme. With Trader Moni, traders receive collateral and interest-free loans starting from N10,000 working their way up to a maximum of N100,000 as the recipients’ payback within a time frame of six months while Market Moni, loans from N50,000 and above.

Chairman of the Yan Doya market confirmed the women’s predicament when he said the intervention did not reach the market even though they had been asked to supply their details. Maigarin Lamido said the N10,000 loans from Trader Moni would have gone a long way in assisting the women and other petty traders.

A little resistance from the next generation

Laraba and Esther did not complete basic education but said they want better opportunities for their girls. “We cannot continue to do this business from generation to generation. We also want our daughters to someday be ministers, governors or commissioners,” said Laraba.

Nancy John said she had the benefit of primary education, but never advanced her education and will now rather concentrate on providing a better future for her kids. But in spite of their encouraging words, the women sometimes force their daughters into street hawking; an activity now receiving subtle resistance from the next generation.

Joy, 19, is Laraba’s second daughter and an SS2 student at the Government Secondary School Kwall. The teenager told our correspondent that she sees herself as a future nurse, not a yam hawker. Her mother, Laraba, said though she hopes Joy actualise her dream, the reality was however not a pretty picture. She explained that she constantly worries over her daughter’s resistance to a trade she said has become the only means of sustaining the education she craves for.

The mother of six also said her eldest daughter Diana has also vehemently refused to trade in yam and insist she wants a better life after higher education. Though our correspondent did not meet Diana, Joy, the youngest daughter expressed the need to cut away from an occupational tradition, she claimed has relegated the female gender of their tribe to breadwinners and yam hawkers.

“I want to go to university and study nursing,” she told our correspondent in Hausa. Joy, however, explained that she helps out by hawking yams during school holidays but admitted that male predators sometimes make advances at her and other young women in the business.“There are times some men will call us to buy yam and instead of pricing the yam, they want to exchange banter with us, they want to invite us into their homes but we are careful, we try to move around in pairs to avoid any form of abuse,” she said.

Esther Sunday also said two of her teenage girls help her with the trade during the holiday season but said they are more focused on getting higher education. “My 18 and 16-year-old daughters feel there is no future for them in this trade and I understand because we didn’t get the opportunities they now have. But what can we do? It is the yam that sustains us,” she said.

A beam of light at the end of the tunnel?

The office of the Social Investment Programme in Plateau State said the yam hawkers could have benefitted from the N10,000 Trader Moni loans disbursed by the Bank of Industry which targets traders in markets, but also said the yam hawkers have a peculiar predicament of roaming around the streets instead of remaining in a specific area.

The Plateau State Focal Person for the Social Investment Programme (SIP) Dr. Sumaye Hamza explained thus: “We could identify their markets and when the agents come, they will then target them, otherwise they will have to form cooperatives, which may be a long process for them because they will have to open bank accounts and they will be assessed before they are given loans.”

She said because the women do not hold any space at the Yan Doya market, it becomes difficult to capture them for the Trader Moni at the market. She, however, said her office will work with some informal leaders among the women to find ways of capturing them around their storage areas.

“We are yet to get details of the consultants that will handle the next phase of the Trader Moni because the Bank of Industry hands over to a consultant to serve as agents. So as soon as we know the next consultants they are sending to Plateau State, we will link up with the agents and see what we can do to support the women,” she said.

Dr. Hamza also said her office could map out the possibilities of linking the women with some community-based Non Governmental financial institutions that are into microcredit with less interest.

On his part, Hon. Agah, who represents Rukuba/Irigwe constituency, agrees that the women need to be stationed in one location where they will attract customers instead of roaming the streets.

The member of the state House of Assembly said he fears that the present nature of the trade exposes the women to sexual and economic abuse. “It is a serious challenge because they are my constituents. There are times I become emotional when I see them backing babies and walking around dark alleys at night,” he said.

Agah assured Daily Trust on Sunday that he would work with stakeholders, including the traditional institutions and the office of SIP to find ways of mobilizing the women to form associations and ensure they have a formal leadership structure so they can attract some assistance from the government.

“We also plan to come up with a scholarship to assist the less privilege; to at least get them educated to the senior secondary school level because most of the children stop at the junior secondary level. We will ensure that the women’s children are part of the scheme,” he assured.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.