A senior White House official known to members of the New York Times editorial board wrote a damning opinion article about President Donald Trump last week, but pleaded that his or her identity be concealed in order to protect his or her job. Since then, forensic linguists and people who care about authorship attribution have been guessing who the writer might be, based on the stylistic imprints of the writings of key members of the Trump administration.

Everyone who writes has a distinctive style mark-favorite words, peculiar turns of phrases, frequently used idioms, etc. Most people who read me, for instance, tell me they can spot my writing from a mile off. Several people have called my attention to plagiarism of my work, and they have been correct. They say, having read me for years, they are so familiar with the rhythm and lexical choices of my essays that they can tell when someone steals them. I can say the same of several people I read, too.

But using stylistic markers for authorship identification isn’t always foolproof. To give another personal example, many people have told me that when my friend Moses Ochonu writes, they think it’s me. We share the same verbal ebullience and verve. We share the same love for expressive and freshness, and our love for and insertion in critical social science and humanities scholarship ensures that we sometimes share the same conceptual and disciplinary vocabularies. Interestingly, people have pointed to the similarities in our styles since we were undergraduates at Bayero University, Kano, in the 1990s. That means both of us can get each other into trouble.

The article I’ve chosen to share with the reader below gives a scholarly linguistic perspective on this issue. Originally titled “The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author,” it was written by James Harbeck and published in the September 6, 2018 edition of The Week Magazine, an influential American-based international weekly. Hope you enjoy it.

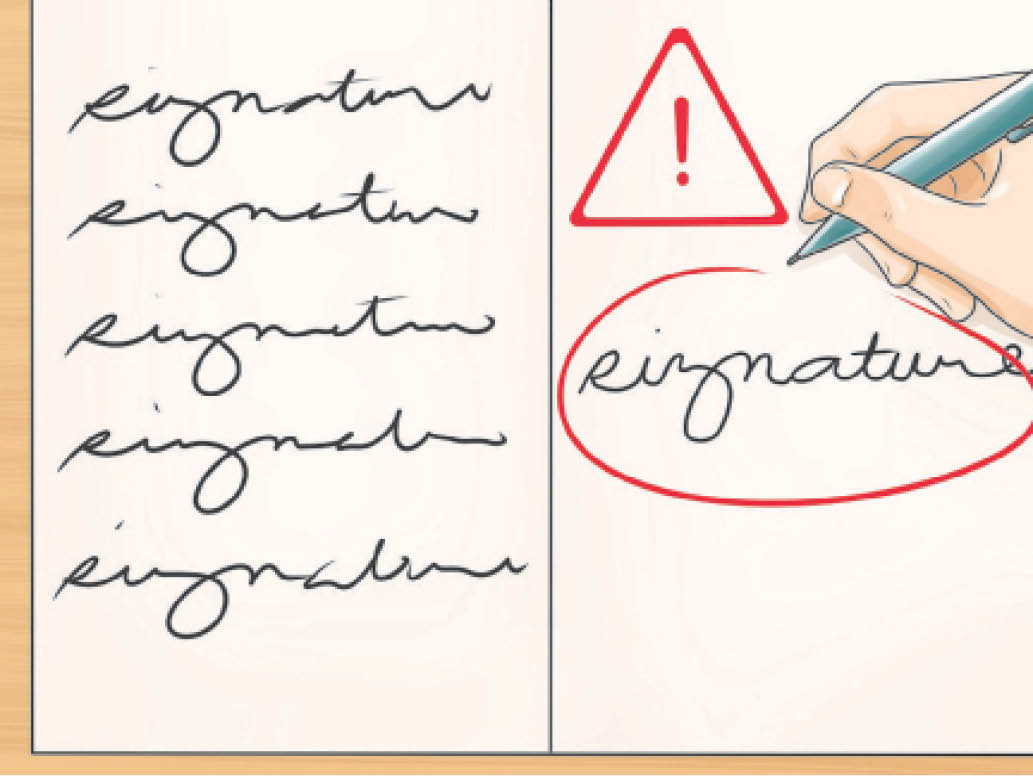

If you handle an object, you leave your fingerprints all over it. When that object is examined closely, your identity can be easily revealed. In a way, the same is true when you write something. Every individual has what linguists call an idiolect: a personal dialect, or a sort of verbal fingerprint left behind in the form of your preference for certain words, phrases, and grammar. Sometimes, these linguistic profiles can help identify an anonymous author.

No doubt internet sleuths have studied the language of an anonymous op-ed in The New York Times to identify the unnamed Trump administration official who penned it claiming to be part of the “resistance.” Some think the word “lodestar” is a linguistic smoking gun, suggesting Vice President Mike Pence could be the author, because he’s used the word in the past.

But, perhaps unsurprisingly, personal dialect forensics is not nearly this simple.

There are numerous examples from history of language being used to trace someone’s identity. In 1887, several letters were published purporting to show that the Irish nationalists led by Charles Stewart Parnell supported violence. But a dramatic cross-examination revealed the letters had been forged by a man named Richard Pigott, a former supporter of Parnell. When asked to write the word “hesitancy,” Pigott misspelled the word as “hesitency,” which had also been misspelled in the letters.

There are other famous cases that make good telling. There’s the Unabomber, whose manifesto looked familiar to David Kaczynski, who noted that some phrases, such as “cool-headed logician,” were favored by his brother Ted Kaczynski in other writings. Ted, of course, turned out to be the culprit. There’s the anonymously-authored book Primary Colors, about Bill Clinton’s campaign, whose author was identified as columnist Joe Klein by a professor of English at Vassar College named Don Foster. Foster’s name pops up often in discussions of forensic linguistics. He identified Klein on the basis of stylistic quirks, such as his liking for words ending in -ish (e.g., wonkish) and certain coinages (such as “unironic” and “tarmac-hopping”). And: a love of colons. More recently, tweets sent by President Trump have been scrutinized and identified as not having been written by him, thanks to peculiar word choices or punctuation (notably, use of en-dashes).

In the 1930s, the man who kidnapped famous American aviator Charles Lindbergh’s son was profiled from the language he used in ransom notes. Authorities were fairly confident the kidnapper was of German origin, given his use of sentences such as, “We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the Polise the child is in gut care.”

These examples make great stories, and it’s tempting to put on your detective hat and scan a piece of writing for tantalizing clues. In real life, though, someone’s identity can’t hinge on a single verbal fingerprint or shred of linguistic DNA. Pigott was already on the witness stand and had been impugned by other evidence. Kaczynski was revealed to be the Unabomber by a large accumulation of circumstantial evidence, of which his writing style (and not just a phrase or two) was telling, but was not the only part, or even the first clue. Several people before Foster had already pointed to Klein as the author of Primary Colors, and he was conclusively identified – and forced to admit his authorship – by the presence of his handwriting on an early manuscript of the book.

That’s not to say that writing style isn’t noteworthy. Indeed, it can matter quite a bit. Malcom Coulthard, an emeritus professor or forensic linguistics at Aston University, has made using language to create reasonable doubt an important part of his career. He has written about a number of cases where people were wrongly convicted of murders thanks to coerced or fabricated confessions. One famous case was that of Derek Bentley, who was convicted of murder in the 1952 shooting of a police officer by his friend while Bentley was already under arrest. A 1991 movie about the case took for its title something he supposedly said to his friend: Let Him Have It, Chris. His conviction was strongly supported by a statement he supposedly gave to police. But analysis of the statement shows that it has some features that are uncommon in ordinary speech – especially for a youth like Bentley – but are typical of the way police officers speak, putting then after the subject, for example, as in: “I then caught a bus” and “Chris then jumped over,” rather than before it (“Then I caught a bus”; “Then Chris jumped over”). On the basis of this and other evidence, the conviction was overturned – in 1998, 45 years after Bentley had been executed.

But as a rule, the way you write is much more fluid and changing and probabilistic than your DNA, which never changes. We write in different ways at different times and in different contexts, and the amount of text investigators have to work with is often nowhere near enough for a detailed statistical analysis, and certainly not enough to show something beyond a reasonable doubt. We’re getting better at sniffing out anonymous authors, but we still have a long way to go.

Can people’s writing styles be used to guess their identity?

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.