Have you ever wondered why English speakers call the boldness that people get after being drunk “Dutch courage”? How about “French kiss,” the kind of kiss where kissers insert their tongue in the other person’s mouth? Why is it called “French kiss”? Why not an “English kiss,” a “German kiss,” or even just a tongue kiss? To “go Dutch” is to equally share the cost of something, such as a meal in a restaurant. Why is that? Are the Dutch such stingy people that one pays for other people? And then you have the idiom “double Dutch,” which means nonsense. Given that English and Dutch are close linguistic cousins, why is “double Dutch” the synonym for gibberish?

Well, if you’ve always wanted to know the historical reasons behind popular geographic idioms in English, the UK Telegraph’s Oliver Smith published an interesting article on November 1, 2017 titled “The fascinating origins of 14 geographical idioms” that I’ve chosen to share with you. Enjoy:

little Dutch courage could be the key to helping travellers speak the local lingo, according to a new study published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology. Which got us thinking. Where does the phrase Dutch courage, and other geographic idioms, come from?

Dutch courage: The best theory behind this expression refers to the supposed use of Jenever-a type of gin-by 17th century Dutch troops, who fought alongside the English during the Thirty Years’ War.

Going Dutch: Britain and The Netherlands were both allies and colonial rivals during this period, while a Dutchman, William of Orange, became king of England in 1689, and these connections can be seen in other common phrases. Going Dutch, or a “Dutch treat”, which refers to the even splitting of a bill, may be a reference to a Dutch door, which is divided horizontally halfway down, but could simply be a derisive term borne out of our colonial rivalry. It’s hardly chivalrous and “English”, of course, not to offer to pay the whole bill.

Other insulting idioms from the era include some still in use, such as Double Dutch (for incomprehensible nonsense) and Dutch uncle (a harsh and unindulgent person), and many others that are obsolete, like Dutch widow (referring to a prostitute), Dutch gold (a cheap alloy resembling gold), Dutch concert (drunken uproar), and Dutch nightingale (a frog).

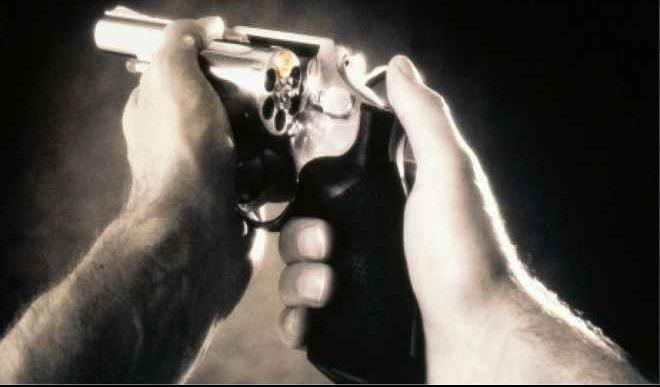

Mexican standoff: A recurring theme in cinema-the conclusion to Reservoir Dogs being a prime example-this expression dates back to the 19th century, and is possibly a result of real experiences during the Mexican-American War or in gunfights with post-war Mexican bandits. It may, however, like the Dutch idioms above, simply be a derogatory term, like “Mexican breakfast” (which refers to a cigarette and a coffee).

Mexican wave: [This is the wave that sports spectators make during games. They stand up, yell, and wave their hands in unison]. There is disagreement regarding the origins of the wave itself, with suggestions that it first appeared at US sporting events during the late 1970s. Krazy George Henderson, however, a professional cheerleader, led the first video documentation of one, on October 15, 1981 at a Major League Baseball game in Oakland, California.

We call it a Mexican wave because of its widespread use at the 1986 FIFA World Cup in Mexico, which was shown to a global audience.

Russian roulette: While the Russian writer Mikhail Lermontov, in his novella The Fatalist, describes a character firing a gun containing an unknown number of bullets at his own head, and surviving, the phrase “Russian roulette” isn’t actually used. Its earliest known use is in a 1937 short story (called Russian Roulette) by Georges Surdez, published in Collier’s magazine. The version he describes, practiced by Russian soldiers, is even deadlier than the one most people think of today – it uses a gun with five of the six chambers loaded, rather than just one.

Chinese whispers: This game, in which whispered messages are passed around a group, gets its name from the general perception that the Chinese language is particularly hard to understand and decipher – in a similar vein to the phrase “It’s all Greek to me”. Until the 20th century it was better known as Russian scandal.

Chinese burn: The practice of painfully twisting the skin is not, as far as we can tell, an accepted move in any form of Chinese martial arts. Calling it a Chinese burn, as British schoolchildren have done for decades, would appear to simply be a novel and exotic name for a devious prank. In North America, it’s better known as an Indian burn.

Indian summer: This probably comes not from British colonial India, but to the American Midwest, where warm weather in the autumn is common, and Native Americans would take advantage of it to hunt and stock up on food for winter. In 1778, a French American, St John de Crevecoeur, wrote: “Sometimes the rain is followed by an interval of calm and warmth which is called the Indian Summer; its characteristics are a tranquil atmosphere and general smokiness.”

Irish goodbye: To leave a social gathering without saying farewell. A great tactic, and it has been suggested that the origins of the phrase date back to the Irish Potato Famine (1845-52), when millions fled the country for the New World. Others, however, claim it is linked to the stereotype of the Irish being heavy drinkers. No one really knows, and the practice has other names, including the French leave, which dates back to 1771, according to Oxford English Dictionary (OED). “He stole away an Irishman’s bride, and took a French leave of me and his master,” wrote Tobias Smollett in The Expedition of Humphry Clinker.

Luck of the Irish: According to Edward T. O’Donnell, author of 1001 Things Everyone Should Know About Irish American History: “During the gold and silver rush years in the second half of the 19th century, a number of the most famous and successful miners were of Irish and Irish American birth. Of course, it carried with it a certain tone of derision, as if to say, only by sheer luck, as opposed to brains, could these fools succeed.”

French kiss: The amorous reputation of the French is to blame for this idiom, which came into use at the start of the 20th century. And the French (who call it un baiser amoureux, meaning “a lover’s kiss”) certainly didn’t invent it – there are mentions of open-mouthed kissing in Sanskrit texts dating back to 1,500BC. Furthermore, it was once known as a “Florentine kiss”.

Our old rivals France appear in several other phrases, most of them uncomplimentary. Such as a French letter (a condom), pardon my French (to apologize for swearing) and the French disease (syphilis).

Glasgow kiss: A tongue-in-cheek reference to the city’s violent reputation, this is a recent addition. The OED reckons a 1982 citation from the Daily Mirror was the first printed use of the term:

“Glasgow has its own way of welcoming people. There is a broken bottle gripped in the fist of greeting. Or there’s the Glasgow Kiss – a sharp whack on the nose with the forehead.” “Liverpool kiss” – meaning the same thing – dates back to 1944.

Sent to Coventry: The events of the English Civil War could be responsible for this one. In The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England, Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, recounts how captured Royalist troops were taken as prisoners to Coventry, a Parliamentarian stronghold.

When in Rome: The oldest saying on our list. St Ambrose is attributed with the phrase “si fueris Rōmae, Rōmānō vīvitō mōre; si fueris alibī, vīvitō sīcut ibī” (“if you should be in Rome, live in the Roman manner; if you should be elsewhere, live as they do there”). A truncated version remains in use 1,600 years later.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.