Even when we were kids in Maiduguri in the 1960s one could safely have forecasted that Tijani el-Miskin, who died recently in the Hajj stampede, would become a scholar. There are three reasons to back up this claim. Firstly, Tijani was to the manor born, in Limanti ward, the intellectual hub of Maiduguri of yesteryears, where the imams, the jurists, and the sheikhs had their sprawling compounds. Limanti is the ward adjacent to the Shehu of Borno’s palace, appropriately on the side of the central mosque, where, when in need, the Shehu traditionally turn for advice with a spiritual and intellectual content.

Secondly, Tijani was a scion of the family of late Sheikh Abubakar el-Miskin, an Islamic scholar, a teacher and community leader, very well-known across West Africa, particularly among the Tijaniyya family. Thirdly, the father’s house was a busy madrasah – an Islamic congregation that attracted students from as far as Senegal. When I struck up a friendship with Tijani sometime in 1969 as fellow students on holiday (he was then finishing School of Arabic Studies Kano, and I was a form three student in Government College, Keffi) and whenever I walked from my father’s house in Fezzan ward to their home in Limanti, I had to wade through and stumble across masses of students of all ages and gender to get to Tijani’s room. His father, Sheikh el-Miskin, ubiquitous at all times of the day, could be seen presiding over different levels of classes of students in many zaures of the house. This was the life, as Tijjani knew it, even before stepping out to the primary school.

As fate would have it, Tijani had a smooth sail through the primary school and was admitted into the School of Arabic Studies, Kano. This was not your run-of-the-mill Arabic school. It had pedigree. Founded in the early 1930s, during the reign of the sagacious Kano Emir, Abdullahi Bayero, the school tried to give well-rounded education with emphasis on the Islamic part. Though the school curriculum changed from time to time, it always retained the same reputation of producing excellent jurists and teachers with sound Islamic knowledge as background.

Even as students on holiday, Tijani was the archetypal scholar, reading and always voraciously reading whatever he could lay his hands upon. He never ceased to be his father’s student, and by virtue of the additional exposure he had acquired, he was of immense assistance to the other students. I was a constant visitor to the house and was also fortunate that we shared common passions for literature for which we never lacked a common subject for discussion at any time.

From the School for Arabic Studies, Tijani moved across Kano city in 1972 to Abdullahi Bayero College then one of the three campuses of ABU Zaria. In the same year I also came in from Keffi to the Samaru campus of ABU to start in the School of Basic Studies. Abdullahi Bayero College, where Tijani was, actually started life as Ahmadu Bello College in 1960 in the premises of the School of Arabic Studies, before moving to its site along airport road. And when Ahmadu Bello University came into being in 1962, the Kano college was renamed Abdullahi Bayero College to immortalize the name of the long-reigning emir (1926-1953) of Kano during whose rule most of infrastructural structures that made Kano into a city were laid.

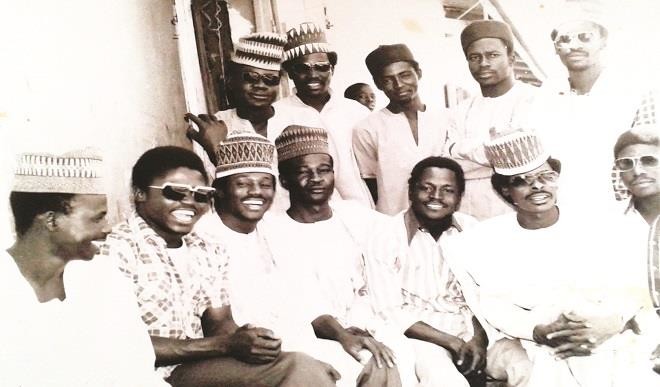

We all graduated in June 1976 and Tijani armed with a degree in Arabic and English was posted to rural Anambra State to serve his time in the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC). I served in Lagos and Tijani visited often along with our mutual friend Bello Abdullahi then also serving In Ogidi, Anambra State. I lived in a one-room apartment in Mende village, Maryland which we all shared whenever they came to Lagos. They used to appreciate my cooking, but my only regret then was that I never got Tijani and Bello to master how to ride on a molue – those garishly coloured big buses, unique to Lagos roads, always full of with sweating citizens.

At completion of NYSC in 1977 we all became employees in Maiduguri. The University of Maiduguri was just starting and Tijani became a foundation staff. In the entire Maiduguri town then there were only a handful of graduates that year. We all knew and related with each other on a daily basis. Even then, Tijani stood out by showing his characteristic disdain for what was grand and fashionable. In those years there were three priorities facing a graduate in Maiduguri. One would quickly become a member of the elitist Lake Chad Club in the Government Reservation Area (GRA), which in those days was a quiet and exclusive suburb. One would then hustle to be allocated a government quarters also in the GRA and then claim the available government loan to purchase a new vehicle mostly from the Peugeot and Fiat series. Tijani would have none of these. He remained in his old room in the father’s house and bought a motor cycle to commute daily from his Limanti ward across town to the University campus on Bama road, till he left for Bloomington, Indiana, United States America (USA), for postgraduate studies a year later.

I, also, shortly after left for Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom (UK), from where, across the seas, we kept a lively correspondence. I followed his advances in the Comparative Literature course he embarked upon, particularly his sojourn into Cuba, Spain and Portugal to soak up parts of Spanish and Portuguese cultures as a means of sharpening his understanding of the languages. It was typical Tijani – what needed to be done well must be done very well! By the time he returned to Nigeria in 1984 with a PhD, he had also become proficient in both languages.

From there his career trajectory could only move but up. He returned to his department in the University of Maiduguri where his passion and newly acquired knowledge and exposure were sorely needed. He helped build the department over the years into one of the most reputable of its type among Nigerian universities. Later, he was courted by his colleague, Prof Munzali Jibril when he was named the first Provost of the Nigerian Defence Academy University, to come and assist to build the institution. Tijani gave his pioneering hand in starting a Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies, before returning to his department in Unimaid. Again the Federal Government headhunted him for appointment as Director, Nigerian Arabic Language Village, Ngala. By the end of his tenure at Ngala, the Institute had become a true hub of Arabic language learning across the country and even beyond. In between he was always in demand to hold posts in other civic and or government organizations. The very last two were as Deputy Secretary, Nigerian Supreme Council for Islamic Studies and Chairman, Borno State Pilgrims Board.

What memories has Tijani left for us today? I remember him as a passionate scholar who was not only keen on seeking knowledge but also on sharing it whether it was within the University, the Madrasah, across Maiduguri town or anywhere else in the country. As one who was ever ready to share his vast knowledge where ever and whenever it is needed, Tijani typifies the best example what should be the relationship between the dons in the universities and the society in general, in effect, between the town and the gown.

Friendship with Tijani was a lifelong tutorial. Whenever you were with him, you always know that he had to learn from you or to teach you. He had a very extensive knowledge of literature in whatever language it is written and I have always been enriched by my association with him. One day sometimes in early 1978 I bought Tayeb Saleh’s book of short stories, ‘The Wedding of Zein’ and presented to him. It was many years later I found out that even before I gave him the book Tijani had not only read the book in its original Arabic form but also he was acquainted with many of the writer’s works yet to be translated into English. Adieu, good friend. Till we meet again.

Dori wrote in from Abuja.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.