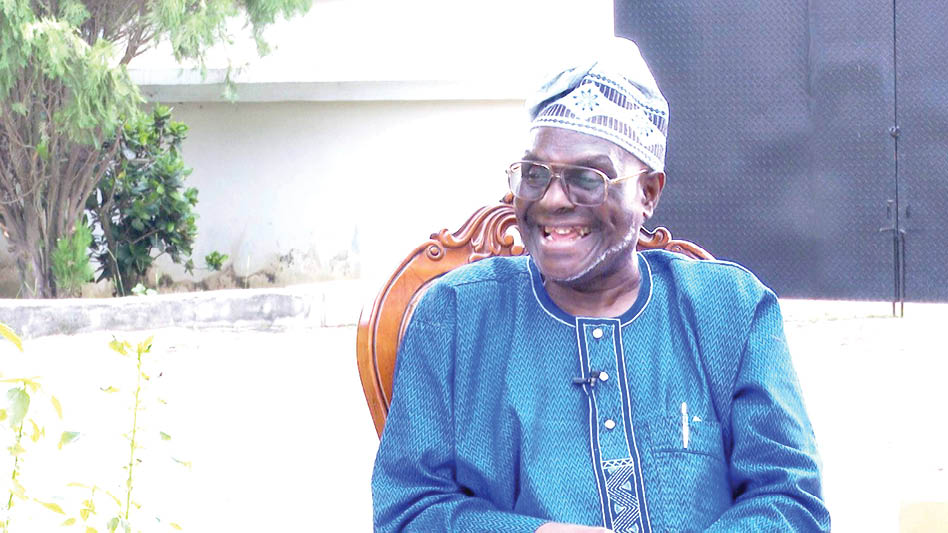

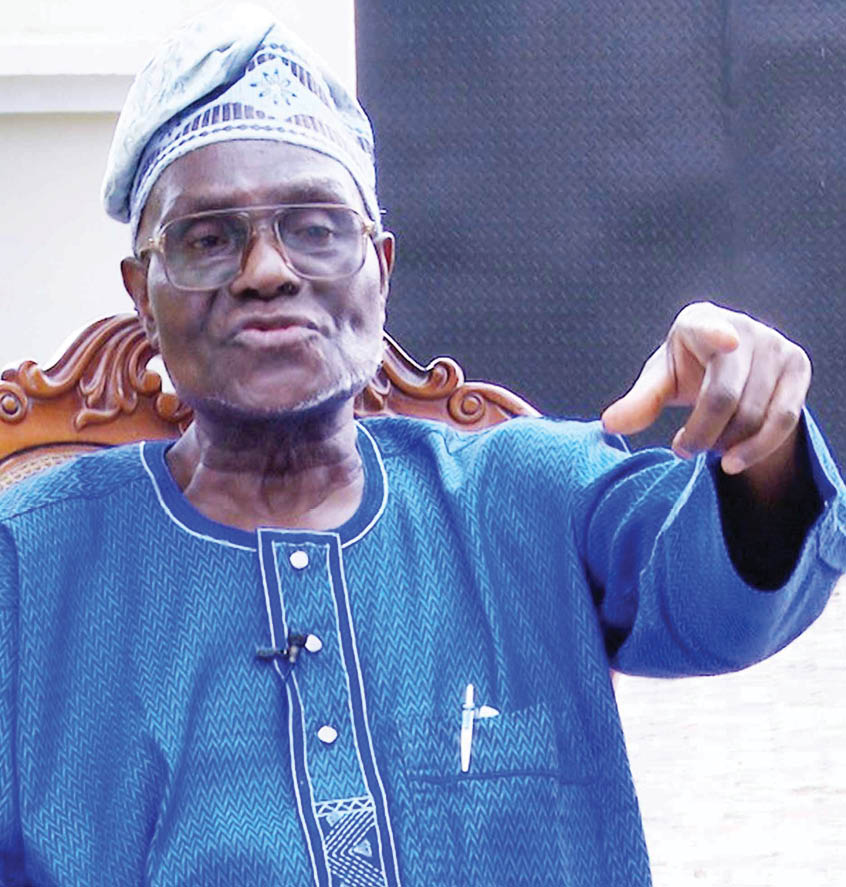

Comrade Hassan Sunmonu is the pioneer president of the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC), 1978-84 and long-time secretary-general of the Organisation of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU). In this interview, he speaks on life as a civil servant and unionist, relationship with his twin brother, their days in Ghana, and some current national issues.

Despite your left-wing orientation, at a young age you were also a Muslim activist. How were you able to do this?

I caught my trade union teeth in the student union movement via the Muslim Student Society of Nigeria (MSS), National Union of Nigerian Students and the National Association of Technological Students. But it is the Muslim Student Society of Nigeria that gave me the foundation for unionism.

How?

At the Yaba Technical Institute, which is now Yaba College of Technology, I was elected, in my second year, as the secretary of the Muslim Student Society(MSS) of Nigeria. But it was a stop gap, in the sense that it used to be the turn of final year students of the college to be elected, but there was a quarrel between our seniors and I was asked to get on as the secretary of the branch.

In that position, my role as secretary was to do wake up during Ramadan and put on water heater for tea or coffee for students that were fasting; then I would go and wake each of them up in their various hostels when the water was ready because the kitchen had already prepared the bread, butter, sardine or eggs.

That was for Iftar?

Yes. Then every Friday I had to arrange for a well-known Muslim scholar in Lagos to come and deliver a lecture to our members and Christians who were interested. Naturally, I was a bit shy in my youth, but that activity took away the shyness.

The first MSS conference I was able to attend, with my twin brother, was in 1962 at Shagamu. At that conference, I and my brother became very popular because we are identical. We were able to mobilise delegates to vote for Oshogbo as the host of that conference.

When we got to Oshogbo, I was elected as the national auditor of the MSS. I was reelected for five years till 1967, when I left the college.

I also became the president of the students union of Yaba Tech. In the 1966/1967 session, I was again elected the president of the National Association of Technological Students, which embraced all the students of colleges of technology and polytechnics in Nigeria.

So, I was holding positions in the students union of the college, the National Association of Technology Students, and as the second vice president of the National Union of Nigerian Students (NUNS), now known as the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS).

- Why administration of LGs was better in 1999 – Ex-LG chairman

- Mambilla: The story of non-Fulani cattle rearers

At that early age, would you say you were already a left-wing radical?

I had not entered the mainstream of trade unionism. When I left Yaba College of Technology after my Higher National Diploma (HND) in June 1967, I reported for work in the Federal Ministry of Works on July 1. The ministry was my sponsor; I was on in-service training.

So, you started as a civil servant?

Yes. In that July, 1967, I was elected the secretary of the Association of Technical Officers of the Federal Ministry of Works. The position was not only for one category of technical officers; it was for all categories – from the assistant technical-officer-in-training to the chief technical officer, all the members.

The major task that confronted the Association at that time was a lot of discrimination. So we were asked to organise a meeting with the permanent secretary in the ministry.

It took us four months to prepare the general meeting, approve the 10 points of the grievances to be discussed. By January 1968, the meeting was granted by the ministry, led by the permanent secretary, the late S.O. Williams.

At the meeting, we presented our grievances and asked for negotiation. The industrial relations officer of the ministry asked whether the Association of Technical Officers, Federal Ministry of Works, was a registered trade union or affiliated to a registered union. The answer to both questions was no. So he told the permanent secretary that there was no need to continue the meeting, saying the people were representing only themselves. We had no platform backed by law. That was the debacle that made a trade unionist out of me.

So, we went back to the drawing board and two of us were asked to do a research of all the relevant trade unions to the Federal Ministry of Works. We found out that it was Public Works, Aerodrome, Technical and General Workers Union, led by Wahab Goodluck, as general secretary.

We brought our report to the general meeting of the association and they approved our recommendation that the association should affiliate to the union.

Those in Aerodrome, in the union’s name, were all the meteorological officers. And you know the meteorological people are the ones who do the forecast etc, they are responsible for forecasting whether planes should take off or land.

Our recommendation was accepted by the general meeting of our association and Wahab Goodluck asked us to sign the check-off. We got our members to sign, signaling our intention to join the Public Works, Aerodrome, Technical and General Workers Union.

Did the radical union background in any way contradict your traditional Muslim approach to life?

I am an Ahmadiyya Muslim. I and my twin brother got married and had a double wedding in the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at of Nigeria. And we have been very active members of the Ahmadiyya since 1967.

I think Ahmadiyya tends to be a bit more liberal, is that correct?

They are actually liberal, but very particular about keeping to the tenets of Islam. My twin brother was also once the Amir of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Association of Nigeria.

On the radical thing you are talking about, Wahab Goodluck, a socialist and leftist, was my mentor. When we joined the Public Works, Aerodrome and Technical and General Workers Union after signing the check-off, he wrote to the Minister of works, stating that the Association of Technical Officers had become members of his Union. And on the basis of that, he asked for negotiation on the 10 points we raised. We went for negotiation and won all the 10 points.

Tell us about your early life in Ghana. It is a well-known fact that you were born there. How did that impact your career?

As a young man, our father left Oshogbo around 1925, to seek his fortune in cocoa business in Ghana. He was a farmer and later became a cocoa merchant.

We were born in Ghana on January 7, 1941. My father told us that it was two days before the Ilya festival. He started to slaughter ram for Hussein and 1 until we started working. When we started working, we continued with the slaughtering every Ilya festival.

At the age of seven, we were brought to Oshogbo because our father had a mortal fear that if we grew up in the Gold Coast, as Ghana was known, we would never come back to Nigeria.

Were two of you the only children of your parents at that time or there were others?

We were the firstborn. We have siblings, including a former Deputy Speaker of the Osun State House of Assembly, Taiwo Sunmonu. They were also brought back to Oshogbo. We were all born in the Gold Coast. None of our father’s children grew up there.

I know there are situations where people, even your mother, find it difficult to separate you from your twin brother; what influence did being twins have on your career?

We arrived in Oshogbo in 1947/1948. Yoruba people actually adore twins; they almost deify them in a way because it is believed that they have very strong spirits, such that even witches and wizards cannot kill them. And if they ever succeed in doing that, they always end up getting mad and people stoning them to death because they would have to confess because of the strong spirit the twins are believed to have.

It is also believed that twins have some elements of luck. For instance, when we were young, people who were selling things around our area in Oshogbo would bring their wares and ask my twin brother and I to touch them, believing that within few hours they would sell out their wares. We were always inundated with gifts because they believed we were people of luck. It was not like that in Ghana at that time. They like twins, but they don’t deify them like the Yoruba.

Did you have the same experience when you were in school?

Yes.

Did you attend the same school?

Yes.

Including Yaba Tech?

Yes.

Did you work in the Federal Ministry of Works at the same time?

We were employed the same day and we got married the same day at the same marriage ceremony. We have always done things together all our lives.

At the secondary school part of the Yaba Tech Institute, I was the only one called for interview and eventually given admission. My twin brother was not called, but because we used to be very religious from our young age, we prayed and fasted together for three days and said that by the grace of Allah, he would also be admitted.

After the interview, I was admitted to do the secondary technical and Hussein was not. At that time, 98 per cent of the staff were Europeans, British mainly; only about two of them were Nigerians. So, two of us went to meet the principal, who was on leave, as well as the vice principal, Mr G. R. Scobee. They prevented us initially, but we found our way.

He wanted to see a distinguishing feature that would make him identify one from the other but he couldn’t. He asked what we wanted and I said we were preparing for an exam but my twin brother was not well, and as a result, he couldn’t prepare well, so he wasn’t called for interview.

He asked what we wanted him to do and I told him that since we were born, we had never been separated for up to two weeks; which was true. I added that if my brother was not admitted, it would have a bad effect on the two of us. He looked again and told the clerk to give him an admission form. That’s how he got in.

When we left the school we were called for interview in the Federal Ministry of Works as assistant technical-officers-in-training. We were employed on September 13, 1961.

Although you are identical, are there some different features between you?

Of course, there must be. I don’t think he is as patient as I used to be. But in generosity, we are the same. And he is very industrious too.

Also, I devote more of my time to unionism than Hussein. But when I was elected the president of the Association of Technical Officers in the Federal Ministry of Works in 1974, Hussein was elected to take my position as the secretary of the association.

I think he ended up as a very senior civil servant.

Yes. Hussein got admission into the University of Leeds in Britain to do his master’s degree in Transportation Engineering and finished in two years, so he was not discriminated against on account of HND qualification.

So, he rose to become a director in the ministry?

Yes. He was even a controller of works in charge of all the 19 states of the North. I think he retired as Deputy Director of Highways.

What does he do now?

He is in retirement.

Is he in Oshogbo like you?

He spends two weeks here and two weeks in Lagos, because his wife is from Lagos State, but my wife is from Oshogbo.

That’s at least one difference between you. Now, let’s talk about trade unionism, where you are best known. At a time you were the president of the Nigeria Labour Congress. I think you were elected because four different unions came together. Can you tell us the background to this?

There were over 1,000 registered house unions in those days, so there was need for restructuring. The military needed to make sense out of the myriad of unions. The restructuring was carried out even for employers. Forty-two industrial associations came out of the 1,000 former house unions. They called it limited intervention.

It was the 42 industrial unions that sent 10 delegates each to Ibadan for the launch of the Nigeria Labour Congress.

At that time, I was not a fulltime unionist; I was working in the Federal Ministry of Works and was elected as the president of the union. The name was changed to Public Works Construction Technical and General Workers Union. I was elected the president of the union on August 1, 1974 in Kaduna while Wahab Goodluck was still the general secretary.

Goodluck was also the president of the Nigerian Trade Union Congress (NTUC). There were four national centres in Nigeria, led by Michael Imodou.

All the four trade unions – NTUC, Labour Unity Front, Nigerian Workers Council and the Nigerian Union of Teachers- did not affiliate.

I was a member of the 50-man steering committee that worked for almost 15 months, till the Nigeria Labour Congress was launched. But the military didn’t recognise it because some of our trade union colleagues, about eight of them, including Pascal Bafyau, Comrades Mbah and Ugbonna wrote a petition.

Against the NLC?

Against the unity of the unions, on the ground that they said the USE was getting a lot of money from the American CIA and that Goodluck was getting a lot of money from the Russian KGB etc, but it was all the handiwork of the government.

That didn’t stop the NLC from coming together?

It didn’t, but they didn’t recognise the NLC that emerged on December 20, 1975. For instance, we didn’t do an actual election as such. What we did was slitting, and it was according to what the leaders of the four national centres decided.

The people who felt sidelined were the ones who wrote petitions to say that the CIA and KGB had infiltrated Nigeria. That’s why they set up the Adebiyi Commission of Inquiry.

The commission of inquiry led to the banning for life of 11 trade union leaders, including Comrade Wahab Goodluck, Comrade S.U Bassey, M.A. Ogbodu. Eleven of them were banned.

From the Federal Ministry of Works, how did you emerge as the president of the central labour organisation in 1978?

First and foremost, the 14 industrial unions had to go to congress and I emerged as the president of the Civil Service Technical Workers Union of Nigeria. Twenty-eight associations were restructured to form the technical workers’ union.

But other leaderships also emerged in the other 41 industrial unions. There was an attempt by the Ministry of Labour officials to dominate and appoint general secretaries for each of the 14 industrial unions. We got wind of that and formed the Association of Elected Principal Officers of Industrial Unions.

Only presidents of the 42 unions?

Yes. We got together and decided that we were not going to allow Federal Ministry of Labour officials to appoint general secretaries for us. As a result of the restructuring that took place, it would be by election. So we had to advertise for vacancies and asked interested candidates to apply through the president of the industrial union. The National Union of Electricity Workers and one other union did the same thing.

That was how we pulled the rug from the leg of the Ministry of Labour officials who wanted to appoint general secretaries for those industrial unions so as to be able to manipulate them.

We had the moral duty to decide who our unions wanted as general secretary etc. When we did that and nothing happened, others did the same thing. It was through our meeting in Ibadan that we got to know one another better.

Dichotomy of sorts was trying to rear its ugly head before we went to Ibadan on February 28, 1978. That was from those who were fulltime trade unionists, not people like me.

So, there was a battle?

That was the ground work that led to what happened in Ibadan.

What was the most challenging thing you faced as the president of the NLC? Was anything more challenging than the strike under Shagari in 1981?

The most challenging thing we had was how to get the NLC and its affiliates established before the lifting of the ban on political activities.

In 1979?

Yes. We were already there on February 20, 1978. It was in October 1, 1979 that the Shagari people came in. It was a race against time that when the politicians came they would like to interfere in our internal affairs and destroy our solidarity and unity.

At the inauguration of the NLC in Ibadan, the Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters, the late General Shehu Musa Yar’adua, who came to represent General Obasanjo, promised that the federal government would give the NLC and its affiliates a N1 million takeoff subvention.

Did you get it?

We didn’t get it until August. It was a race against time.

So, the challenge was how to get your state chapters off the ground?

Yes. Not only state chapters but the industrial unions themselves to really spread all over the country. In fact, we got our state councils on before most of the industrial unions got theirs state chapters.

State chapters of the NLC were actually helping industrial unions that were not fully established in the state to defend the interests of their members. That was the great challenge we had.

And thank God that we were able to do that because the N1 million subvention was released in August and each industrial union was given N10,000, which amounted to N420,000; and N580,000 was left with the Nigeria Labour Congress.

When we got that money we bought a bus and went to launch councils all over the 19 states at that time.

What led to the 1981 strike? And what kind of pressure did you face as the president of the NLC in calling for the industrial action?

First, it was due to the insensitivity of the federal government at the time. We wrote a number of letters and there was no response. Workers were suffering and we wanted the situation to be addressed, but they said no.

And workers were not supposed to be unhappy with their salaries because those were the days when Nigeria had a bit of money, right?

Yes. We also had some other things, such as the need to declare May Day as a public holiday.

So, it wasn’t allowed, up to that point?

No. We did it on our own. We started it in 1980; and by 1981, six progressive states like Lagos, Oyo, Kano and others declared May Day as public holiday.

So, during the 1981 strike, we presented the declaration of May Day as workers’ national day in Nigeria as part of our negotiation, in addition to minimum wage, housing and a lot of other things.

How did Shagari take it? Did he engage you in a bid to stop the strike?

Yes. A day before the May 11 strike, he asked the secretary to the government, the late Alhaji Shehu Musa to phone me and ask me to come to Ribadu Road. Three times I refused because it was too late, and if I went, they would say the government had given me something. But when he phoned the fourth time, I thought it was also not good manners for me to reject the invitation of the president. I insisted that the president would allow one of my deputy presidents and my twin brother to come with me. Ali Ciroma, the deputy president, was in Maiduguri, so he couldn’t make it, so I insisted that the Nigeria Union of Petroleum and Natural Gas Workers (NUPENG) president, John Dubre, who was the second deputy president and was in Lagos, should accompany me.

There was the fear that we might get to the gate of Ribadu Road and they would just shoot us and put some fake guns on us to say that we had gone to assassinate the president.

So, you really felt threatened during that period?

Of course.

Was there any attempt to arrest you?

No. When we met the president, he said we should stop the strike, but I told him that it was too late.

How many days was the strike?

Just two days.

Was it the only strike during your tenure as NLC president?

It was the only one.

In the last one year, I believe the NLC has gone on strike two or three times. Do you think the times call for that, or there is a different mood in the labour union? Are you surprised when you see what is happening now?

I think the insensitivity of those in power is the major cause of the strikes. As a union, how can you write the government about what workers are facing and you want it addressed and there will be no response?

And leaders have to report back to their members. If the government doesn’t abide by its own type of agreement, what do you want the workers to do? So I am not surprised.

Do you think workers were right to have asked for N400,000 as minimum wage?

That’s a bargaining thing; it is not the final demand. We also asked for N300 minimum wage in our own time.

You asked for N300?

Yes; before we eventually got N100 and N95 for housing and some transport allowance in addition.

Are you still consulted by the NLC?

Oh yes.

Are you part of the whole struggle up till now?

Trade union leaders don’t retire; we are on the reserve list to be called upon by those in charge when the need arises to give one piece of advice or another. I am also a trustee of the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU). I have joined ASUU’s negotiating team several times.

Considering agitations for minimum wage and improved condition for everyone of us, not just workers, what would you advise the government to do?

Our government should not follow the advice of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank because their role is to collect debt for their principals in the West. The World Bank will not give you any advice that will make your own people to survive.

So, you are either a friend to the IMF and enemy to your own people or you are a friend of your own people and enemy to the financial institution; you cannot be both.

The structural adjustment programme we rejected in the early 1980s is now what our own present federal government is embracing through the IMF and the World Bank. It has failed throughout the third world.

Also, you have asked Nigerians to make sacrifices; what is the sacrifice of the political leadership? They have not made any sacrifice but they are asking the people to tighten their belts, even when they are dying of hunger.

You have not reduced the price of petrol or that of gas and electricity and you are telling Nigerians to make sacrifices. Everything has been jerked up, making life difficult and forcing factories to close and causing unemployment and you are still telling the people to make sacrifices. I don’t think they have a good economic team in this government. I may be wrong but that’s my opinion.

You spent many years as the secretary-general of the African Trade Union Organisation. You were in Ghana for so many years doing that job. What has that taught you about things beyond Nigeria?

What the position taught me is to think pan-Africa, because an injury to one African country is an injury to all of us. Two, our slave drivers have vowed never to let any country in Africa emerge as the Asian Tigers.

We have a proverb that if somebody is deceiving you, must you deceive yourself? You shouldn’t deceive yourself.

They are leading us more into debt, insolvency and instability; must we follow their path? If we don’t break that chain, there will be no stability in any country in Africa.

As a pan-Africanist, what comes to your mind when you see what is happening in Kenya? Do you think there are similar reasons for young people here to also protest?

It is a wake-up call for all other African countries. You ask people to tighten their belts but you have not tightened your own as leaders. Now, we are hearing that they want to establish their own hospitals when Nigerians are dying of hunger. Is that supposed to be their priority?

They shouldn’t let people think they are selfish, insensitive, unpatriotic and visionless.

If one looks at pan-Africanism as an ideology, it seems not to have made much progress from the 1960s. We are still divided as African countries; that’s why we can’t visit one another without visas. There is still a lot of antipathy, even in Ghana where you spent so much time; what do you think?

With all due respect, I don’t share your view. First and foremost, Africa’s economic integration is moving. It may be slow, but it is moving. Look at the ECOWAS and other regional entities. We are making progress. Don’t forget that the progress is sluggish because of those who don’t want us to come together like one family. They don’t want to see that in Africa, an injury to one is an injury to all. They don’t want to see us emerge. They don’t want to see any superpower emerge within the African continent.

Unfortunately, they are bringing us all sorts of things that are capable of reducing our population. Recently, they said they were having some inoculation for 14-year-old girls. They are sterilising those ones against the future and Nigerians should never accept it. They say that Africa is overpopulated, but how?

Africa is larger than the United States, China and India put together. China is just one third of the land area of Africa, and it is over 1.4 billion population. What population do you have in Africa, but they say we are overpopulated. And they are coming to say they are bringing one healthy thing to help out. No!

What do you do in retirement? How do you occupy your time?

I am a religious person, so I have time to devote to the worship of Allah and my Zikr. Secondly, I have enough time to also assist trade union colleagues who need my advice. Then, I have almost completed writing my memoir.

That’s interesting. When do we expect it?

Insha Allah, by the end of this year it will be out. The manuscript is what I am going through now. I want to include a 93-year-old Sri Lankan, Mr Pereira, who was my engineer when we were doing the National Arts Theatre in Lagos.

So, I have not been lazy. Also, as a trustee of the ASUU, when they call me for meetings, I go for them.

What about the NLC?

I call them when I feel that something is wrong. NLC veterans are very active.

Are you in touch with your old colleagues in the NLC?

Yes; people like Osidipe, P.B. Okoro and Ojerin, who died last year. Ali Ciroma also died. So, some of them are dead.

Do you see yourself doing some economic activities like farming or consultancy to survive?

I don’t do any consultancy. And what type of farming can I do?

But pensions don’t seem to be enough for retirees; is that correct?

My children are taking very good care of us.

Tell us more about your family life.

In September it will be 55 years of marriage to the same woman.

So, you were never tempted to go beyond that?

No.

And children?

I have three men and three women. When I went to Lagos, I stayed with our eldest son. The Ibrahim you saw is my personal assistant; he is the only one virtually living with us and in charge of everything in this house. When we are away for anything, he gets everything fixed.

One of the sons is in Canada with his wife. My eldest daughter is working in a multinational company called Axion. My middle daughter, who is the number five, is working in the Commonwealth Secretariat, London. She is a desk officer. And the youngest is a medical doctor and an assistant professor at Yale University in the United States. I am here with my wife and one of my sons.

What do you do for pleasure?

Yes. Our daughter has a small farm not far from here, so I do some activities there.

Do you engage in any physical exercise to keep fit?

I and my wife used to walk, but because of kidnapping and things like that, we stopped. So, most of the time, we just go round the house here.

Do you still travel?

Yes. During our last birthday in January, our children took us to Kenya. My wife and I have the same birthday, on January 7, but with a four-year difference. We had 10 days in Kenya, during which we went to Nairobi and Mombasa. At times they ask us to go to Canada or US.

My wife doesn’t like travelling a lot, but I enjoy it. She is always afraid of travelling. She will not sleep, even if it is 18 hours of flight, but within 5 minutes after takeoff, I am already gone.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.