Nigeria’s security challenges are multifaceted and deeply intertwined with the development and sustenance of its democratic institutions. This report produced for Daily Trust by Dr. Kabir Adamu, the Managing Director of Beacon Consulting Limited, a renowned firm providing enterprise risk and security management solutions in Nigeria, examined the security challenges that has come with Nigeria’s democracy since 1999, their impact on governance and proffered pathways to improve the nation’s security for better democratic dividends.

Despite restoring democracy in 1999, after 29 years of military rule, which marked the commencement of the Fourth Republic, Nigeria continues to grapple with various security threat elements that pose significant risks to its stability and democratic governance.

These threat elements including violent extremist groups like Jamatus Ahlis Sunna lil Dawatil wal Jihad, the Islamic State in West Africa Province and Ansaru fi Baladil Sudan popularly called Boko Haram, wreak havoc to particularly the Northeast and more recently parts of the Northcentral and Northwest regions of Nigeria, while secessionist agitations, inter-community violence, extra-judicial killings including by state security forces, banditry and kidnappings and resource-based conflicts plague these three and the other parts of the country.

The drivers of the insecurity include bad governance, ineffective and inefficient justice systems that fail to arrest and punish offenders, inability to introduce adaptation measures for climate change, weak border control measures, weapons proliferation, drug challenges, socio-economic and political grievances, absence of social cohesion, the collapse of the value system, a defective election system, lack of effective security system and geopolitical influence. Some of these challenges stem from poverty, social inequality, and a legacy of military rule. The multiplicity and continued occurrence of security challenges undermine public trust in the government and weaken democratic institutions, creating a vicious cycle where instability breeds more insecurity.

First Ladies: Their Fashion , Influence

FG flags off distribution of 1,000 gas cylinders to FCT residents

Security sector governance in Nigeria in the last 25 Years

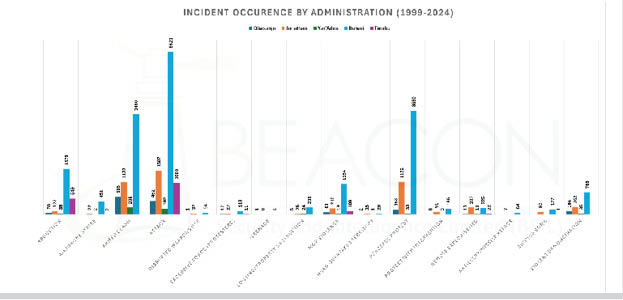

Over the 25 years of uninterrupted democratic governance, Nigeria has been governed by two political parties; the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), which was in power for 16 years (1999 – 2015) and the ruling All Progressives Congress (from 2015). In this period, Nigeria had five presidents: Chief Olusegun Obasanjo (PDP, 1999-2007), Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’Adua (PDP, 2007-2010), Dr. Goodluck Jonathan (PDP, 2010-2015), Muhammadu Buhari (APC, 2015-2023), and Bola Tinubu (APC, incumbent).

Nigeria returned to civil rule in 1999, with Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, a former military ruler emerging as a civilian elected president. Under his two-term presidency, the country experienced varied forms of threat elements including ethnic and religious violence, resource control agitation resulting in violent conflicts in the Niger Delta, violent criminality and alleged use of the instrument of state to stifle opposition.

The administration’s attempt to address corruption and some of the other challenges led to the establishment of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC; 2003), the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC; 2000), and the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC; 2000). Also, he dissolved and banned some ethnic groups such as the Asawana Boys in Niger Delta, Oodua Peoples Congress (OPC) in the Southwest, and Bakassi Boys in the Southeast. Some major criticisms that were associated with his administration’s security sector governance included heavy-handedness, a lack of respect for human rights and international humanitarian laws and the alleged use of some security sector organisations to stifle opposition and the press.

Under the short regime of Umaru Yar’Adua, he used both kinetic and non-kinetic means to address the insecurity challenge. These included his crackdown on the burgeoning ideological insurgency, Jaamtus Ahlis Sunna lil Dawatil wal Jihad that metamorphosed into the monster to be known as Boko Haram.

Others are the creation of the Amnesty Programme and the Niger Delta Ministry (2008) aimed at addressing the long-standing issues of militancy and violence in the Niger Delta and offering an unconditional pardon and financial compensation in exchange for their demobilization and disarmament.

During the Goodluck Jonathan administration, Nigeria battled with the Boko Haram insurgency, which escalated during his tenure and by 2013, had become the world’s most deadly terror group.

Other challenges faced by that administration included corruption, the Ebola outbreak, protests and strike actions over fuel subsidy removal, and the abduction of Chibok Girls by Boko Haram insurgents.

To tackle these challenges, he took steps to strengthen Nigeria’s counterterrorism capabilities, including increasing military funding, improving coordination among security agencies, and seeking international assistance to combat the insurgency.

He further attempted to promote democratisation through the observance of the rule of law, the enactment of the Freedom of Information Act, electoral reforms and non-interference in electoral outcomes. One of his most remarkable attempts was the 2014 National Conference, which came out with several recommendations to achieve national integration and address the root causes and drivers of insecurity as well as the structural deficiencies triggering conflict in the country which he failed to implement.

Nigeria under the Muhammadu Buhari administration despite massive investment which improved the capacity and capability as well as the equipment repository of the security forces, suffered an increased spate of banditry in the northern states, farmer-herder violence, the COVID-19 pandemic, and EndSARs protest.

To tackle these challenges, the administration in addition to forging regional cooperation and investing massively to increase the security force’s capabilities and equipment repositories introduced a controversial National Livestock Transformation Plan and its Rural Grazing Area (RUGA), created to modernise cattle grazing and stabilise the middle belt region. Also, he initiated the Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project (HYPREP) over the intermittent attacks on oil facilities by groups such as the Niger Delta Avenger.

In 2016, he negotiated a deal with the Boko Haram insurgents which secured the release of some Chibok Girls. Overall, he fought the Niger Delta oil thieves, the Islamic Movement in Nigeria, an umbrella body of Shia Muslims, led by Sheikh Ibrahim Zakzaky, Biafra separatists, Boko Haram, and Ansaru but was unsuccessful in finding a lasting solution.

Some major criticisms that were associated with his administration’s security sector governance included heavy-handedness and human rights abuses and lack of respect for international humanitarian laws as well as the alleged use of some security sector organisations to stifle opposition and the press.

The current administration of Bola Ahmed Tinubu like its predecessors is prioritising security but so far has not succeeded in containing the multifaceted threat elements that continue to cause national security challenges including attacks by non-state armed groups such as the ideological terror groups and bandits mainly active in parts of northern Nigeria, social upheaval in the form of protests over the cost of living crisis triggered by removal of fuel subsidies and floating of the national currency, the Naira.

This economic challenge has widened the structural deficiencies that are aiding and forging the drivers of insecurity in Nigeria.

It is therefore not surprising that despite a visible renewed and revamped security forces operation and intelligence gathering capabilities that have led to the killing and arrest of some non-state armed groups’ commanders, kidnapping, banditry, and farmer-herder conflicts have remained credible threats to national security. The administration is also failing to convene and hold regular security council meetings but opted for adhoc arrangements outside the constitutional structures.

State of democracy and its impact on national security

Over the last 25 years and even though the 4th republic is the longest in the history of Nigeria, there is a consensus that the electoral system in Nigeria remains defective and is yet to meet the expectations of most stakeholders particularly the millions of Nigerians who yearn for change and an improvement in their quality of life and standard of living.

Various administrations over the past 25 years attempted to improve Nigeria’s electoral system by amending the Electoral Act but the search for a free fair and equitable election in Nigeria remains elusive.

A free, fair and transparent electoral system can impact national security by allowing open discussion of security issues, enabling the identification of root causes, and holding the government accountable for its responses. It can also impact national security by engendering peaceful resolution of conflict.

Impact of insecurity on democracy

The protracted insecurity in Nigeria has resulted in an erosion of public trust, suppression of civil liberties, distraction from development and in some instances, especially during elections or electioneering period, the weaponisation of violence to achieve political influence and shape outcomes.

The intertwined nature of security challenges and democratic governance in Nigeria cannot be overstated. This is because the erosion of security undermines the rule of law, stifles political participation, and exacerbates social tensions, thereby posing a direct threat to the consolidation of democracy.

In regions affected by insecurity, citizens’ ability to exercise their democratic rights, such as voting and freedom of expression, is severely curtailed, leading to disenchantment with the political process and a sense of alienation from the state.

Pathways to improved national security

Our analysis of the 25 years of democratic security governance in the fourth republic shows the following trends that have served to prevent the attainment of Nigeria’s national security imperatives.

First if the legacy of military rule, which infers that security sector governance in the last 25 years has suffered from the vestiges of the long years of military governance and a failure to implement effective security sector reform. For example, former military personnel mostly retired continue to hold security sector leadership without understanding the expectations of their position in a democratic system.

In addition, a significant number of the laws that govern the security sector were enacted during military governments and very little has been done over the last 25 years to democratise these laws. This means elements of human rights abuses and lack of respect for democratic traditions and the rule of law are still affecting security sector implementation in Nigeria.

Another trend is that the security sector over the last 25 years has suffered from weak performance measurement and oversight. The structures for internal and external performance management are either weak or non-existent. However, the Buhari and Tinubu administrations have made progress in this regard, with the institutionalisation of Executive Order 13 and the functions of the Central Delivery Coordination Unit.

For this effort to be effective, the security sector’s ministries, departments and agencies should embrace metrics and strengthen their monitoring and evaluation as well as standards departments.

Additionally, the oversight functions of the National Assembly have been abysmal. The general perception is that the parliamentarians and their staffers have not develop technical competence for oversight functions and that corruption too has played a role.

The third trend is that the corollary of weak performance measurement and oversight has been the almost total absence of consequences for failure in the security sector over the last 25 years. Security sector officials in Nigeria who have failed to carry out responsibilities or who either as a result of poor judgement or unprofessionalism allowed major security lapses to occur with significant consequences including loss of lives and damage to property have not been adequately penalised. There are so many examples in the 25 years including the Chibok abduction, the Kuje prison attack, the Abuja-Kaduna train attack and the Owo church attack.

The final trend is that of the non-implementation of security sector provisions. The 25 years have generally shown a poor tendency to observe and implement security provisions in the constitution including regular security, defence and police council meetings, and implementation of security sector strategies policies and laws. These are corollaries of the weak performance measurement and oversight challenges.

National security in Nigeria involves the state’s ability to implement appropriate policies to meet citizens’ needs and ensure the right atmosphere is provided for the attainment of goals and aspirations. There is a need for a focused disaggregation of Nigeria’s security challenges and pursuing conscious efforts to build national consensus and an all-of-government and an all-of-society approach to addressing them. Here are some recommendations:

1. Addressing the root causes of insecurity: Poverty contributes to insecurity, limited opportunities, scarcity of resources and social inequality. Investing in education, job creation, and social safety can aid in sustaining security, reducing violence, and maintaining long-term stability. In addition, elections have to be free and fair and reflective of the peoples’ choices.

2. Strengthening good governance at the federal and subnational levels: Robust anti-corruption measures, improved transparency, and accountability are crucial as is inclusion.

3. Community engagement: The Nigerian Police Force, a key institution for law enforcement, should prioritize community policing and foster partnerships with local actors. However, public confidence in the police is low due to non-performance and corruption. The Federal Government should develop a decentralized security strategy, focusing on rural areas. This will help build trust and improve the country’s democratic government.

4. Improved intelligence gathering and management: Building a stronger intelligence apparatus can aid in providing proactive measures, guide security forces to specific targets, disrupt the activities of criminal organisations, and prevent violence.

5. Regional cooperation: Some threats transcend national borders, and enhanced regional cooperation in intelligence sharing and joint operations can be highly effective.

6. Promoting national integration and achieving social cohesion: Promoting tolerance, inter-religious dialogue, and peacebuilding as well as conflict resolution through the fostering of transitional justice.

7. Judicial reform: A fair and efficient justice system is essential and ensures accountability for security forces.

8. Regulation of small arms: Stricter controls on the proliferation of small arms and light weapons are crucial.

9. Border security: Fortifying the borders can help reduce violence, maintain regional stability and create a more secure and stable environment.

Other strategies include counter-terrorism, conflict resolution, international cooperation, socio-cultural re-orientation, and the use of technology.

Democracy and security are interconnected and require a holistic approach. Nigeria faces complex security challenges, but by addressing insecurity’s root causes, strengthening democratic institutions, fostering community engagement, and adopting a holistic security approach, the country can create a more secure environment for its citizens.

A strong democracy is not an end goal, but a tool for building a nation where security and development are interconnected. To maintain a democratic state and recognize the efforts of security agencies in controlling threats, power should return to Nigerian citizens by eliminating corruption in both the political system and security institutions.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.