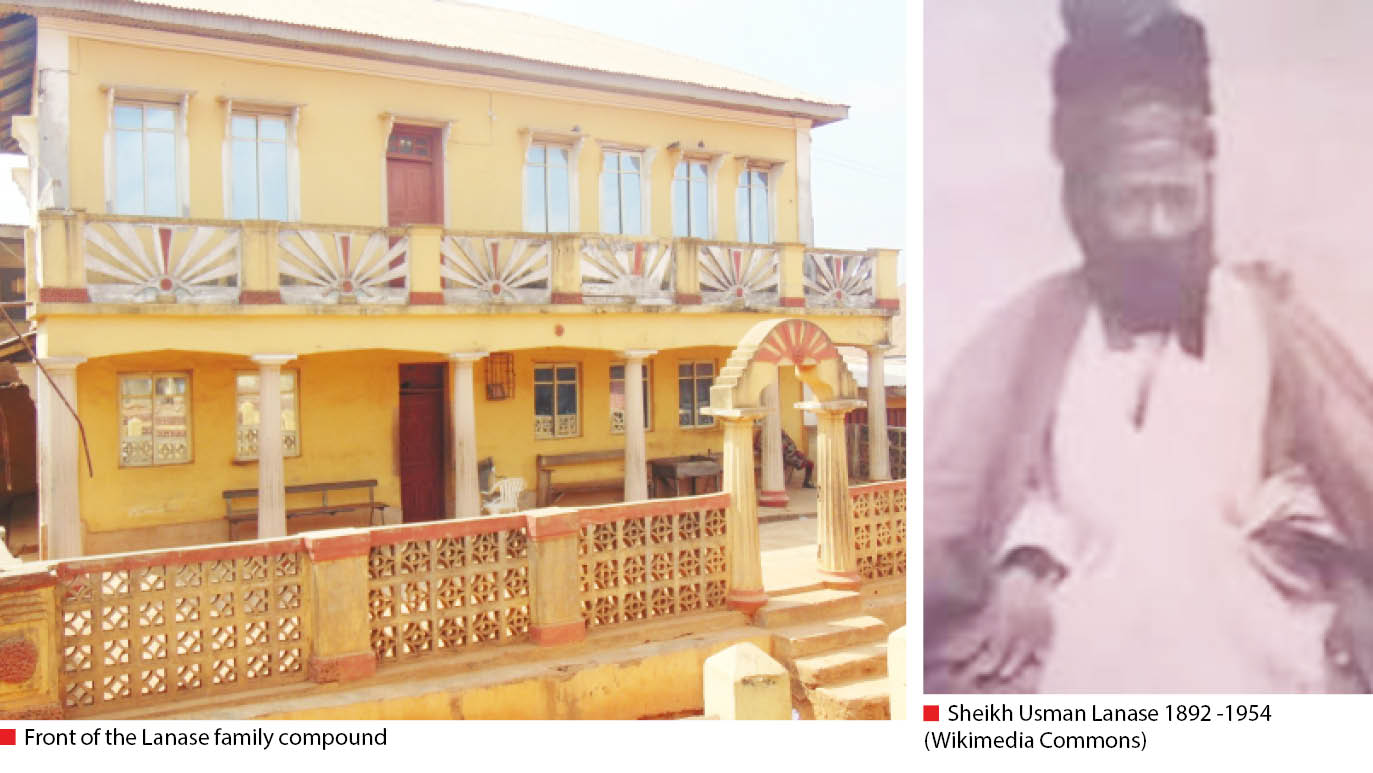

Zaria is mentioned many times while discussing the life and career of Sheikh Usman Lanase. Of Yoruba and Hausa parentage, he straddles two centuries. Born in Zaria in 1892, he was at the height of his gifts in the following century. He had a ‘magnetic mind’ (Wikimedia Commons) which was apparent to one of his teachers in Zaria and there are hints that he might have been clairvoyant.

Imam of Sabo

Sa’ad Abubakar—the Imam of Sabo Ibadan, told me last December of the Lanase family, drawing attention to the place of Zaria in the family story. He mentioned that the family hails from Zaria. The family actually hails from Ibadan and there is, however, a strong umbilical connection to Zaria.

Olanase is the full version of the family’s surname, Lanase being a slightly abbreviated rendition, and it has the combined impression or meaning of abundant wealth, spiritual wealth in this case.

Lanase is a part of Ibadan located in the Ibadan North East Local Government Area. The family home is to be found there and a number of small and large alleys can be found in the immediate area bordering the house. Nearby is the white Sheikh Usman Lanase Mosque which has a prominent minaret.

We’ll resume payment of wage award this week – FG

IOCs’ divestments: FG tasks indigenous firms as operators list constraints

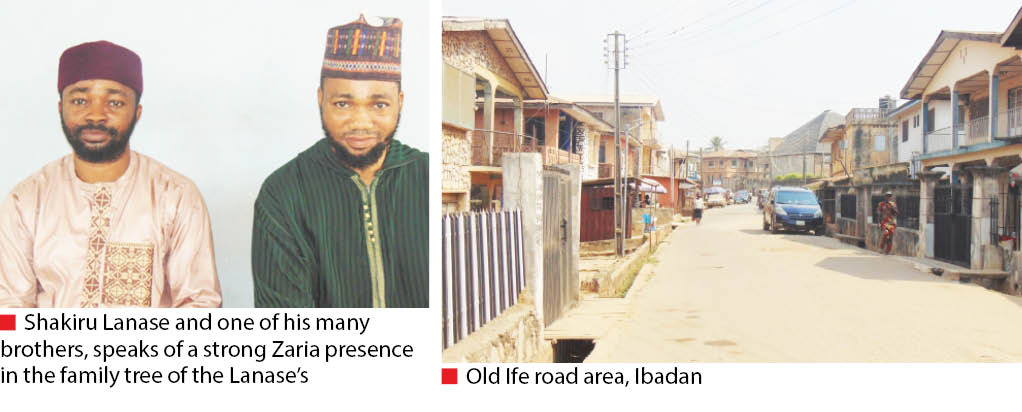

Shakiru Lanase, the Sheikh’s fair-complexioned great-grandson, recalls the life of his eminent forebear in a mosque near the old Ife Road Ibadan.

Assimilation

“We don’t have problems with people here. Our fathers told us that there were problems long ago. At that time, they would not invite him to events. They said he was Hausa. Now, nobody says we are Hausa, they understand that we are Yoruba.”

Lanase revives the family name

To establish his Yoruba roots as a reaction to the widespread belief that he is Hausa, Usman Lanase revived his family’s surname which had, for reasons that are not very clear, gone out of use. This is a form of cultural archaeology carried out by Sheikh Lanase, resurrecting a name that had been used three centuries ago. It is unclear where it was previously in use since Ibadan itself came into being in the 19th century. Surely, if a name was in use in the 17th century, then it must have existed in a territory outside of Ibadan, which itself came into being in the 19th century.

According to his great-grandson “Lanase brought the name from the 17th century. Everybody in the family had already forgotten the name. As my great-grandfather came back from the North, he began telling them about the family story, and everybody agreed.” The name which had withered for lack of use, now returned in full bloom and has remained till this day.

“The family had used the name Ayodabo before reviving the name Lanase. When Sheikh started preaching in Ibadan, people were saying he was Hausa. So, he resurrected the name so people would stop calling him Alfa Oja gbo, and insisted he is Sheikh Usman Lanase.”

Oja gbo is the name of the community in Ibadan where he lived at a time. Thus, he had been referred to as the Alfa or cleric of Oja gbo.

Turban

Upon returning to Ibadan in 1938 many Alfas or Islamic clerics thought he was Hausa, pointing to the manner he wore his turban which was tied around his head in the Sokoto style or after a fashion common in Sokoto even today. They did not know that he was as Yoruba as many of them, with a distant forebear who was a Yoruba warrior. Having grown up in Zaria, Usman Lanase was dyed—in a manner of speaking—in the social ecosystem of the North where ethnic identities may sometimes be fluid rather than fixed. This fluidity of identities is also true of the South. As it is in the north, so is it in the South.

Alfa, Mallam

“In Yorubaland, they call mallams or Islamic clerics Alfa, in the North Alfa is called mallam. People were saying that there were many Alfas in Ibadan who understood Arabic much more than Sheikh Usman Lanase. So, there were quarrels between the Sheikh and the other Imams.” This gives an idea of the social milieu Lanase bumped into shortly after arriving in Ibadan.

Travelling clerics

His life shows that movements by Islamic clerics across the 19th century went in two directions: One was a movement from the North southwards as seen in the career of Uthman Basunu, a story published by Daily Trust last Saturday.

The other wave was a movement from the South, especially from Yorubaland, northwards to some of the principal trading cities such as Kano, Zaria and Katsina which also had significant populations of Muslims and a large number of Qur’anic schools and clerics.

People move

“Connections between old Oyo and Hausaland, Hausa city-states, Kano, Katsina, Rano, Zazzau, and many others, has been going on for a long time, even before the 19th century. The 19th century crises including the trauma of slave raiding, despite abolition, the jihad, did not prevent the migration of people. People continued to move. As people moved to the north, people also moved to the south,” states Professor Rasheed Olaniyi of the Department of History, University of Ibadan, shedding light on movements by Islamic clerics within the central Sudan in the 19th century.

Fond of Zaria

Shakiru Lanase smiles occasionally and his voice rings through the quiet mosque where we are seated. According to him, “Usman Lanase’s father’s name was Yusuf and his mother was Aisha, and she was of both Hausa and Fulani derivation. But her father was Yoruba from Ibadan. Usman Lanase’s father was born in Yorubaland and he used to go to Zaria to work and get jobs to raise money.”

Imprint

The imprint of Zaria, the principal city in the Zazzau Emirate in Kaduna State, looms large in the Lanase family memory. There are marital connections to Zaria going back to the early part of the 19th Century or even earlier, as well as links forged in the context of trade and the quest for Islamic scholarship. Some names and details have been forgotten owing to the passage of time, but there is no doubt that the Lanase family has a strong bond with Zaria.

Zani Abdulrahman

Sheikh Lanase’s great-grandson sheds more light on the family’s growth and development. His words “When Sheikh Lanase was three years old, his father took him to a Sheikh called Mallam Zani (Sani) Abdulrahman, a citizen of Zaria. There were three clerics in Zaria at the time and these included Mallam Zani, Mallam Tukur and Mallam Nahaya. His father took him to Zani Abudulrahman for him to receive Islamic knowledge.”

Don’t beat him on the head

The young Lanase was gifted in many ways and his father seemed to have been aware of this. This realisation informed his advice to the Islamic cleric in Zaria, whose school he was attending.

His words “He told Mallam Zani that the child should not be beaten on the head and that he can be beaten on any part of the body, but not on his head. You know in the olden days and up till now, when they are guiding the pupils who have not read as expected of them, they will take the cane and beat every one of them,” explains Lanase.

Electric shock

He continues “But he mistakenly beat him on the head as he used to do with the other pupils. Immediately he did that, the mallam received something like a shock or a current passed through him. He now told Usman Lanase to sit in a separate place, apart from the other pupils.” This is significant.

40 years studying

There followed many years of learning and scholarship. Lanase says “Sheikh was with his mallams for almost 40 years. He read the Quran, concluded the Fikr, and he went through much in terms of Islamic knowledge. He stayed with Ustaz for three years and could read the Quran clearly. Then his father took him to Kaduna to Mallam Abubakr and there he memorized the Quran completely. After Sheikh had been with Mallam Abubakr for four years, they now took him back to Zaria to continue his studies.”

Ibadan beckons

Lanase continues with his narration on the life of Sheikh Lanase “When Sheikh was 30 years old or thereabouts, his master died. Before his master died, he used to tell him that he would want to go back home to Ibadan, when he had finished his studies, so that his people would benefit from his knowledge.”

Two sisters

He adds “Meanwhile, he had two sisters, Zainab and Jamila, who were with his parents in Zaria. Both of them had died, leaving Usman Lanase and his parents. His father was scared that Usman may die in Zaria and that he should quickly take him to Ibadan. Later, Lanase’s father went to the mallam to give him the excuse that he wants to take him to Ibadan to see his father’s place of origin.

“Sheikh then travelled to Ibadan with his father and he was taken to the Lanase area. He introduced him to the first family home which was at Itabale. The second one was at Lanase. The second one is where Sheikh Usman Lanase migrated to when he later returned to Ibadan.”

A dilemma

“Later, he went back to Zaria and then his teacher died. At that point, Usman Lanase wanted to stop going to the madrasa to now go back to Ibadan. By then something happened in the madradsa. The first child of his malam, Mallam Mukhtar, was very young by then and he didn’t know how to teach others at the point his father died. He just knew how to read the Quran and some other texts and his daddy had more than a hundred students. Sheikh Lanase was scared and wondered what would happen after he left and continued to stay with Mallam Mukhtar.”

Lanase guides Mukhtar

Sheikh Lanase now had to carefully guide Mukhtar. He had a strategy which he put into effect “Sheikh called Mallam Mukhtar late in the night to teach him one or two lines. By 4am, he will call him and tell him that this is what you will tell me in the morning when people are sitting in front of you. Just call me and don’t ever let anybody know. When it is time for Islamiyya study, Sheikh will sit like they are all expecting to receive knowledge together. Then Mallam Mukhtar will call Shehu out and begin to teach him one of the difficult books of the Qur’an which is not easy to understand. That was how he taught Mallam Mukhtar until he knew everything completely. Then Sheikh decided to move to Sabon Gari Zaria to have some freedom.”

Two wives

Pupils from different Islamic centres began to flock to Sabon Gari and this affected Mallam Mukhtar’s school which now began to get empty. Then, Sheikh decided to go back to Mukhtar to revive the school. After the school was revived, Sheikh migrated back to Ibadan. By this time, he was married and had two children. His wife was Mallama Rabiya, a lady from Zaria, and the daughter of Malam Sani Abdulrahman.

Family tree

Lanase opens up on the family tree “The mother of my father is Mallama Rabiya. They are from Zaria. The mother of Sheikh Lanase was Hausa Fulani from Zaria. The three wives of our great-grandfather are from Zaria.”

He identifies names on the family tree “my daddy was born by Sheikh Usman Lanase and Sheikh Lanase was born by Yusuf. Yusuf was born by Yusuf Ayodabo and Yusuf was born by Ewumi. Ewumi was the father of Osadipe. There are one or two before Lanase, our most distant forebear. I cannot remember all of them. His real name is Lanase and some people say he was one of the warriors of Yorubaland.”

Kofar Doka

He sheds light on the link with Zaria “We have members of our family in Zaria. Some of them were living in Lanase here at a time. They have a house there. They come from Zaria and we too do go to Zaria. Their house is in Kofar Doka, Zaria. They trace their roots from the great grandmother on the mother’s side, and not the father’s side.”

Baba Lamadu

He continues “We still have connections with Zaria. Baba Lamadu in Zaria was the firstborn of the mother of my father before she married Shehu Usman in Zaria. Mallama Rabiya is the wife of Sheikh Usman Lanase. Before she married Sheikh Usman Lanase, she was divorced by someone. The only child she had was named Baba Lamadu. After Baba Lamadu, she married our great-grandfather and gave birth to Muhammadu Qazeel, my father.”

Reviving Hausa roots

Shakiru Lanase married a lady from Kano partly to preserve the Hausa line in his family, which had somewhat been in decline. In this sense, he acted in ways similar to his forebear who revived the family name to make a statement. Marriage thus becomes a form of cultural excavation. Selecting a partner from the north revived a marital pattern that was once very visible in the family.

He explains “My daddy was born by a Hausa lady and his father also married from the north. My great-grandfather also married from the north. Then I asked why this tendency had stopped. When I was young, I felt I should have a Hausa wife. My great-grandfather’s parents married from the north. At least 3 generations married from the north, and there is a long history of marriage from Hausaland. I was disturbed that this pattern was broken, so I renewed the cycle by marrying from Kano.”

He has 40 brothers and he is the only one who openly stepped out to marry from Hausaland, he tells me. He married Aisha who hails from Kano, five years ago.

Lanase in Ibadan

“When Sheikh Lanase arrived in Ibadan, he liked mixing with the Hausas of Sabo, people used to come here too from Sabo. His wife will also go to Sabo to mix with the Hausas there, that is, Mallama Rabiyat. The people in Ibadan, the Alfas, were surprised, doubting if the Sheikh is Yoruba. They will always say he is Hausa, not Yoruba. They pointed to his turban saying it is tied in the Hausa fashion,” explains Lanase whose late father gave a lot of information on Sheikh Lanase. Upon the latter’s return to Ibadan, he set up the Institute of Arabic and Islamic Training in Aremo, Ibadan.

Hausa or Yoruba?

Many questions were asked when Sheikh Lanse turned up in Ibadan and set about preaching “All other mallams were disturbed, asking why all Yoruba mallams will go to Sheikh Lanase when we have our mallams. They didn’t know that the sheikh is Yoruba and that he hails from Ibadan. But some enlightened people brought their children to learn from Sheikh Lanase. These were people from Sabo, Ibadan.”

Sheikh Lanase’s Prayer mat

Shakiru Lanase talks about a matter which he describes thus “It is very difficult to believe.” He states “Sheikh Usman Lanase never collected money from anybody but he used to spend money. When people come to him for money, he will lift his prayer mat and the exact money you ask from him will be there. In Yorubaland, people sometimes speak of an Alfa in the following words ‘All Alfas that spend money from the prayer mat’. Those words were praises directed at Sheikh Lanase.”

He explains “It’s not all Alfas that have the power to take money from a prayer mat. Only if you keep your money there, then you can take your own money out. When Sheikh Usman Lanase needs money, he will open the prayer mat and the money will be there.”

In this vein, Wikimedia Commons argues “The popularity of Sheikh Lanase had reached great heights because of the miracles that surrounded his learning prowess and behaviour.”

Karamat

“Having gone through trainings, which ordinary people failed to go through or could not go through, they became strong spiritually. There were no prophets at the time any more, but they became mystics and miracles usually happened through them. They have what we refer to in Islamic mysticism as Karamat. Karamat is when the seemingly extraordinary happens through your intervention, then we refer to that as Karama. We don’t refer to it as miracles,” states Professor Afis Oladosu of the Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies, University of Ibadan. He was opening up on the extraordinary events which are sometimes attributed to Islamic clerics.

Ibadan, not Zaria

Wikimedia Commons states that Sheikh Lanase was born in Ibadan and this contradicts part of the above account which points to Zaria as his place of birth. It states “Sheikh Lanase was born in the historic city of Ibadanland, his father’s name was Baba Lanase; he was one of the great warriors of Ibadanland.” In a telephone interview on February 13, 2024 to cross check this information, Shakiru Lanase reiterates the fact that Sheikh Usman Lanase was born in Zaria.

The bottom line is that a gifted and impactful cleric with a ‘magnetic mind’ who emerged from a Yoruba family that looked towards Zaria, once flourished in Ibadan, mentoring hundreds of Alfas in the process. This much is clear. Usman Lanase passed on in 1954 at the age of 62.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.