After several appeals by residents of Kurmin Kaduna in Igabi Local Government Area of Kaduna State for a junior secondary school, respite came when the Kaduna State Government granted the approval that has seen many girls, including housewives, make efforts to complete secondary education that was once stalled by lack of access and early marriage.

It’s been 20 years since Aisha Aliyu, 35, found herself within the four walls of a classroom. She now sits on a wooden desk she shares with two girls.

Draped in a navy-blue hijab that covers a white long-sleeve gown and trousers, which she wears as school uniform, Aisha became a student of the recently approved Junior Secondary School, Kurmin Kaduna, one of the state’s oldest communities. She joined her classmates to read from a textbook with a character that coincidentally bears her name.

“This is Aisha, she is 10 years old…” the mother of six, read, joining other students to chorus the content of the book, as a volunteer teacher standing in front of the classroom listened.

- Kogi Gov, SDP Guber Candidate Trade Blame Over Attack

- Subsidy removal: FG must commit to ameliorative policy

Aisha joined Mardiyya Aminu, 33, Bilkisu Abdulrahman, 28, and three other housewives to return to school. The women, aged between 22 and 35 years, plan to complete their junior secondary education, which stalled due to lack of access and early marriage.

“We only had a primary school in Kurmin Kaduna,” Aisha said, referring to the community’s dilapidated primary school that has existed since 1975.

“In 2002, after completing my primary education, marriage became the only option,” she added.

The nearest junior secondary school from Kurmin Kaduna is Government Secondary School, Rafin Guza, which is less than three kilometres from Aisha’s community.

River Kaduna, a 550-kilometre-long tributary of the Niger River, keeps girls from continuing with their education because the trip to the school requires a risky canoe ride. By land, a long, winding dirt road that stretches about 20 kilometres cuts off Kurmin Kaduna from other urban communities, making it hard-to-reach.

While most boys from the community continued with their education at Rafin Guza, many women in Aisha’s age group ended at primary school and were married off at the age of 15.

To get to a secondary school, the boys relied on a 30-minute canoe ride from Kurmin Kaduna to get to one of the two canoe posts at Rafin Guza and Malalin Gabas.

For Aisha and other girls, the absence of a bridge between Kurmin Kaduna and Rafin Guza meant they either had to take the boat ride or forfeit their education. The fear of drowning – something which often happened due to the unworthiness of the boats – discouraged the girls and their parents from taking advantage of the daily boat ride to cross the river and pursue their secondary school education.

“Girls are not taught to swim, but the boys learn to swim at an early age,” explained Mardiyya Aminu, a mother of four, who, like Aisha, has returned to school. Aminu brings her 9-month-old twins to class. Mardiyya said although it is free for all students to hitch a canoe ride, canoe paddlers prefer to accommodate their paying passengers before allowing the students to board.

“Often, the canoes capsize because they are old and are often overloaded. When this happens, majority of the women and girls drown as they cannot swim. It is mainly because of this that our parents asked us to forfeit junior secondary education,” she said.

Dayyabu Adamu, whose daughter was married at 15 seven years ago, said boys often learned to swim at an early age, but the river is no place for girls or women who want to swim.

“Swimming involves exposing the body, something that is frowned at in Islam and is against cultural practices which demand that girls and women cover their bodies,” he said.

Aisha Aliyu’s father, Mohammadu Aliyu, corroborated this, saying, “Our girls cannot swim and the canoes sometimes capsize. The paddlers often delay them because they will have to convey their paying passengers before they consider the students. Often, there is a struggle between the boys and girls to get into the canoes and the boys have a better chance of fighting for space, which means that the girls end up getting to school late.”

He said the girls were frequently caned because of getting to school late. Moreover, most parents could not afford to take their daughters to boarding schools or provide facilities where they could stay to avoid the risky daily crossing. This discouraged the girls from attending secondary school.

How community got state government to approve school

In July 2022, the Kaduna State Government approved a junior secondary school for Kurmin Kaduna following several appeals by youths and leaders of the community. The government had approved the community’s primary school: LGEA Kurmin Kaduna as a temporary learning space for the now 108 students, including Aisha Aliyu and Mardiyya Aminu.

Kurmin Kaduna, a farming and fishing community, is surrounded by Unguwan Kudu, Mashigi, Makwalla, Kahuta, Unguwan Tudu, Sabon Garin Tudu and Kurmin Kaduna Gari communities. The eight communities have no secondary school, but share three primary schools, amongst them LGEA Kurmin Kaduna, LGEA Kurmin Kaduna Gari and UBE Unguwar Tudu. The absence of a bridge to connect the communities to Kaduna metropolis makes boat ride the fastest and easiest means of transportation.

Dauda Ismail, the chairman of Kurmin Kaduna Youth Action and Awareness Forum, said the community had been worried about the decline in girl-child education and made several verbal and written appeals between 2019 and 2022, through the local government, their legislators and the state government.

“Finally, the state government approved a junior secondary school, but it is yet to build structures and deploy teachers to the school,” he said.

Without waiting for the government to make necessary learning facilities available, residents of Kurmin Kaduna commenced tutorials to get the students ready before the deployment of government-approved teachers.

Ismail and 9 other male graduates and Nigerian Certificate in Education (NCE) holders from the community now volunteer as teachers. They teach English, Mathematics, Home Economics, Arabic, Agricultural Science and Hausa Language.

The action of the people of Kurmin Kaduna is a show of community ideas and solidarity that can produce the needed results, according to Maikano Madaki, a professor of Sociology at Bayero University, Kano.

Professor Madaki said that for sustainability, the community needs an established system of community involvement in managing the school and providing support services to the needy.

“There should be an established system of leadership, source of funding and supervision.

“Different sectors and segments of the community should be involved in the execution of its activities. People in the community must be made to feel that they own community activities,” Madaki said.

Girl-child enrolment on the rise

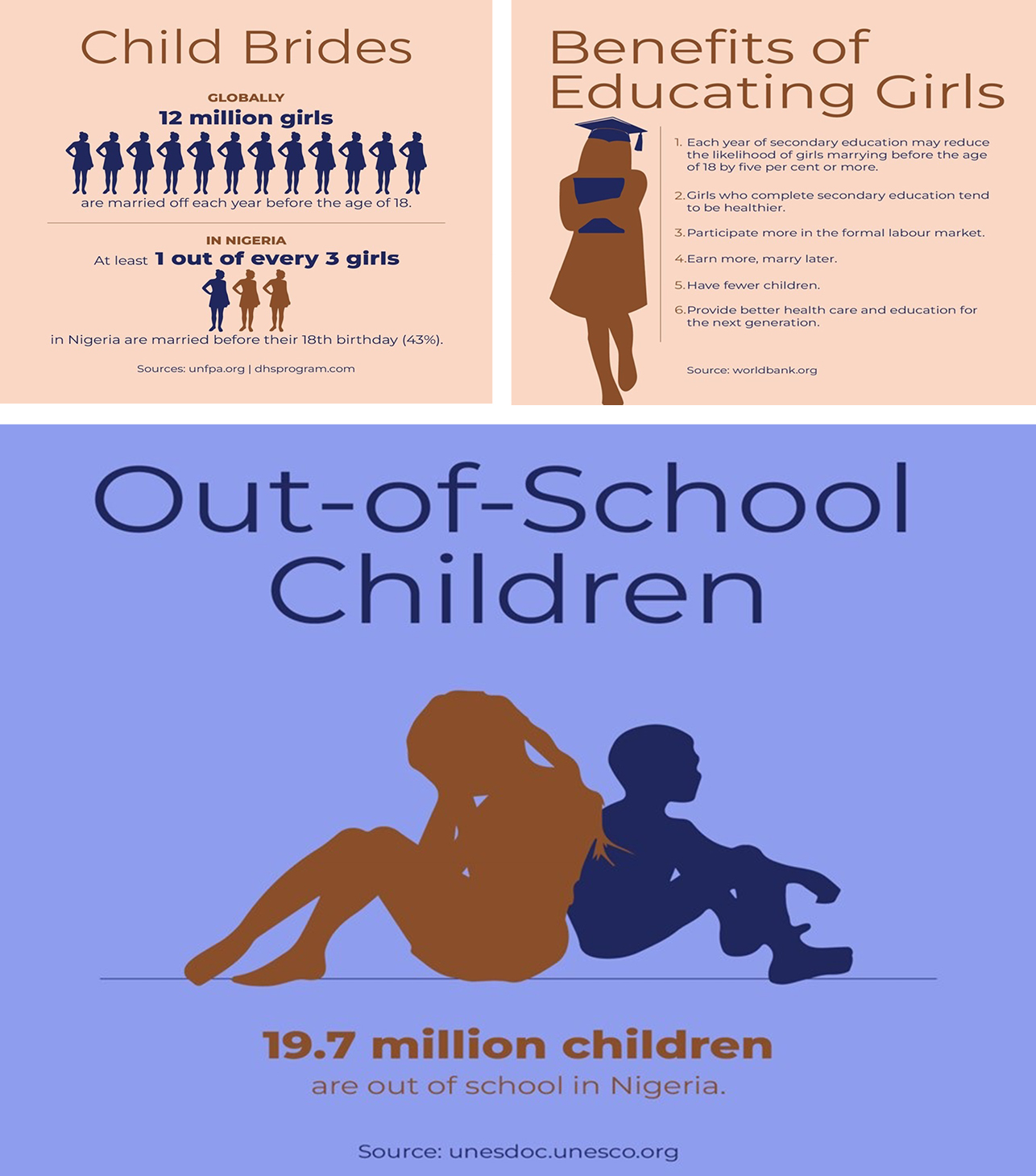

Each year of secondary education may reduce the likelihood of girls marrying before the age of 18 by five per cent or more, according to the World Bank. The bank also states that girls who complete secondary education tend to be healthier, participate more in the formal labour market, earn more, marry later, have fewer children and provide better health care and education for the next generation.

By taking advantage of the new junior secondary school in Kurmin Kaduna, 14-year-old Hauwa Aminu may have been saved from becoming one of the world’s 12million child brides married off each year before the age of 18, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Having completed her primary education in 2019 at the age of 12, Hauwa remained at home due to lack of a junior secondary school although she yearned to be in school.

“When the new school started, I told my father that I wanted to complete secondary education before marriage. I told him that I wanted to be a doctor and he agreed,” she said.

Even as they sit in two classrooms of the 48-year-old dilapidated primary school with volunteer teachers, the enrolment of girls is on the rise, said Dauda Ismail, the chairman of Kurmin Kaduna Youth Action and Awareness Forum.

“There are 108 students that have enrolled so far. Out of this number, we have 64 females and 44 males,” Ismail said.

Bilkisu Abdulrahman, 28, whose education was cut short after she married at 15, has also returned to school.

“Even if I don’t get employment in future, my children could benefit from the knowledge. I will be able to assist them with their homework. With time, I could reach out to other families and help other children also,” she said.

Prof. Madaki explained that such ambition displayed by Bilkisu was part of the ripple effects expected from the community’s action.

“It means that within the next few years, the community would have everyone educated—both males and females,” he said, adding that by enhancing education opportunities for women and girls, the community will not only promote gender equality but encourage women and girls’ involvement in community activities.

“They (women and girls) can contribute their own quota to the development of the community. There will also be provision of quality training and socialisation to the children since more married women in the community will have or acquire education,” he said.

Prof Madaki added that school dropouts would reduce in the community as almost all the children would be in school and there would be a reduction in juvenile delinquency and crime, and there would be improved security.

“Family institutions would be much more peaceful, organised, and rational in decision-making. Women and girls would be elevated to a height where there would be an improved economic system, stability and enhanced community consciousness,” he added.

According to the United Nations, rural women’s access to education and training has a major impact on their potential to access and benefit from income-generating opportunities and improving their overall well-being. Although the right to education is a fundamental human right, this does not apply in many developing countries such as Nigeria, where limited or no access to education for women is one of the major barriers that hinder overcoming hunger and providing a healthy life for children.

At Kurmin Kaduna, although the primary school where the housewives and other students take their classes is dilapidated, with only few habitable classrooms and some students sitting on bare floors, the poor learning condition has not deterred them.

“Every day, we see girls coming; and some of them are married and accompanied by their husbands. We also noticed that the women are very talented because their performance is high. But we need better structures and qualified teachers to motivate more to come to school,” Ismail said.

Explaining the situation in the school, the desk officer for Upper Basic Education in Igabi LGA of Kaduna State, Salisu Turunku, said although the state government had approved a junior secondary school for Kurmin Kaduna, as a norm, the primary school would serve as a starting area. He said the state government planned to construct a junior secondary school within the primary school.

“This means that they will be using the classes in the primary school pending when the government builds structures for them. Soon, teachers will be deployed to the school,” he said.

Bridging the out-of-school children gap

The most recent Global Education Monitoring Report by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) puts Nigeria’s current out-of-school children at 19.7million, with girls forming 60 per cent of the deficit.

The country’s large population of out-of-school children are predominantly from the northern part of the country, according to the World Bank, which also factored the lack of access to secondary education as significantly higher in the northern part of the country where the ratio is up to 10 primary schools for every secondary school.

The UNICEF identified geography and poverty as important factors in the pattern of educational marginalisation, with education deprivation in northern Nigeria driven by various factors, including economic barriers and socio-cultural norms and practices that discourage attendance in formal education, especially for girls.

Like the case of Kurmin Kaduna, hard-to-reach areas across Nigeria face education deprivation with opportunities for better secondary schools in most rural than urban areas.

Kaduna is one of the seven states benefiting from the Adolescent Girls Initiative for Learning and Empowerment (AGILE), a World Bank project with the goal to improve secondary education opportunities among girls in targeted areas.

The Component Lead, Digital Literacy for AGILE in Kaduna, Sani Aliyu, explained that the lack of safe and accessible learning spaces within schools was one of the factors that affect girls’ education.

“Some schools do not have teachers while there are no schools in some communities,” he said.

To address this demand-constraint, Aliyu explained that the project would in 2023 construct 155 schools, out of which 90 would be junior secondary schools and 65 senior secondary schools across the state.

“They, especially junior secondary schools, will be constructed within the premises of the existing schools,” he said.

After searching through records, Aliyu confirmed to Daily Trust Saturday that the school in Kurmin Kaduna, where 108 students, including Aisha Aliyu, Mardiyya Aminu and Bilkisu Abdulrahman have returned to fulfil their dreams, was not captured in the intervention.

“There are criteria for citing the schools; one of them is that the distance between an existing secondary school and a primary school should not be below four kilometres. So, where we have more than four kilometres, that is where we consider the new construction,” he said.

Rafin Guza, where boys from Kurmin Kaduna have over the years benefitted from junior secondary education, is only three kilometres away but separated by River Kaduna, which remains an obstacle for the girls of Kurmin Kaduna. Without a bridge to link Kurmin Kaduna to Rafin Guza, the river puts girls at a disadvantage.

Even as they sit in two of the most habitable classrooms in a dilapidated primary school that bears the brunt of age and poor maintenance, Aisha and the other women are hopeful.

“I returned to school because I want to become a pharmacist someday. I want to own a chemist shop, and to do that, I need to know what drugs to sell and how to administer them,” she said.

This report was supported by the Africa Women Journalism Project (AWJP), in partnership with the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ) and the sponsorship of the Ford Foundation.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.