In the changed economic environment marked by a resurgence of inflation and high debts in Nigeria and across the globe, central banks must adopt new approaches in their efforts to attain and maintain macroeconomic stability, economists have said.

They must look for alternative measures or combinations of policies rather than relying on monetary policy as an effective tool to fight inflation, they argue.

“This is a period in the history of the world with global GDP at an all-time high of over $100 trillion, but also the highest level of debt in history, of over $300 trillion. So, the world economy is three times over-leveraged, with 300% inflation,” Bongo Adi, an economics professor at the Lagos Business School, told Daily Trust in an interview recently.

“This is the problem. We have a situation where debt is being compounded by high inflation. This has never happened from my understanding of the modern economy,” he declared.

For Nigeria, Adi says the authorities should consider adopting “a combination or mix of policies that are not necessarily monetary because monetary policy will not work.”

Adi’s position has been corroborated by those of Markus Brunnermeier, a Princeton University economics professor.

“Now, a resurgence of inflation requires yet another shift in emphasis in monetary policy. The predominant intellectual framework central banks have followed since the global financial crisis that began in 2008 neither stresses the most pressing looming issues nor mitigates their potential dire consequences in this new climate,” Brunnermeier wrote in the March edition of IMF’s F&D, under the title, ‘Rethinking Monetary Policy in a Changing World’.

He argues that while financial stability remains an important concern, “there are important differences between the current environment and the one that followed the global financial crisis”.

Like Adi, Brunnermeier acknowledges that public debt is now high, which means that “any interest rate increase to fend off inflation threats makes servicing the debt more expensive—with immediate and large adverse fiscal implications for the government”.

He notes further that monetary policy requires a modified approach that is robust to sudden and unexpected changes in the macroeconomic scenario. According to him, policies that are effective in one macroeconomic environment may have unintended consequences when conditions suddenly change.

Both economists agree that the current resurgence in national debts is traceable to the COVID-19 pandemic when national governments engaged in expansionary monetary policies to counter the impact of the lockdowns that marked the period.

“This debt has its origin in the bailout and lax monetary policies – known as quantitative easing – that many governments embarked on in order to save their economies from the impact of COVID-19,” Adi said.

“They signed money to help households to smoothen the deleterious effects of COVID. They supported companies that could not produce during the period. This was simply printed money so the money supply increased. That means that government debt increased; household debts also increased,” according to Adi.

Distinguishing the current scenario from what was obtained during the 2008-9 global financial crisis, Adi points out that then, the world had a high level of debt, but low inflation. With that low inflation and high debt, the government “can print money with monetary policy, using expansionary monetary policy rather than a contractionary policy to reflate the economy.”

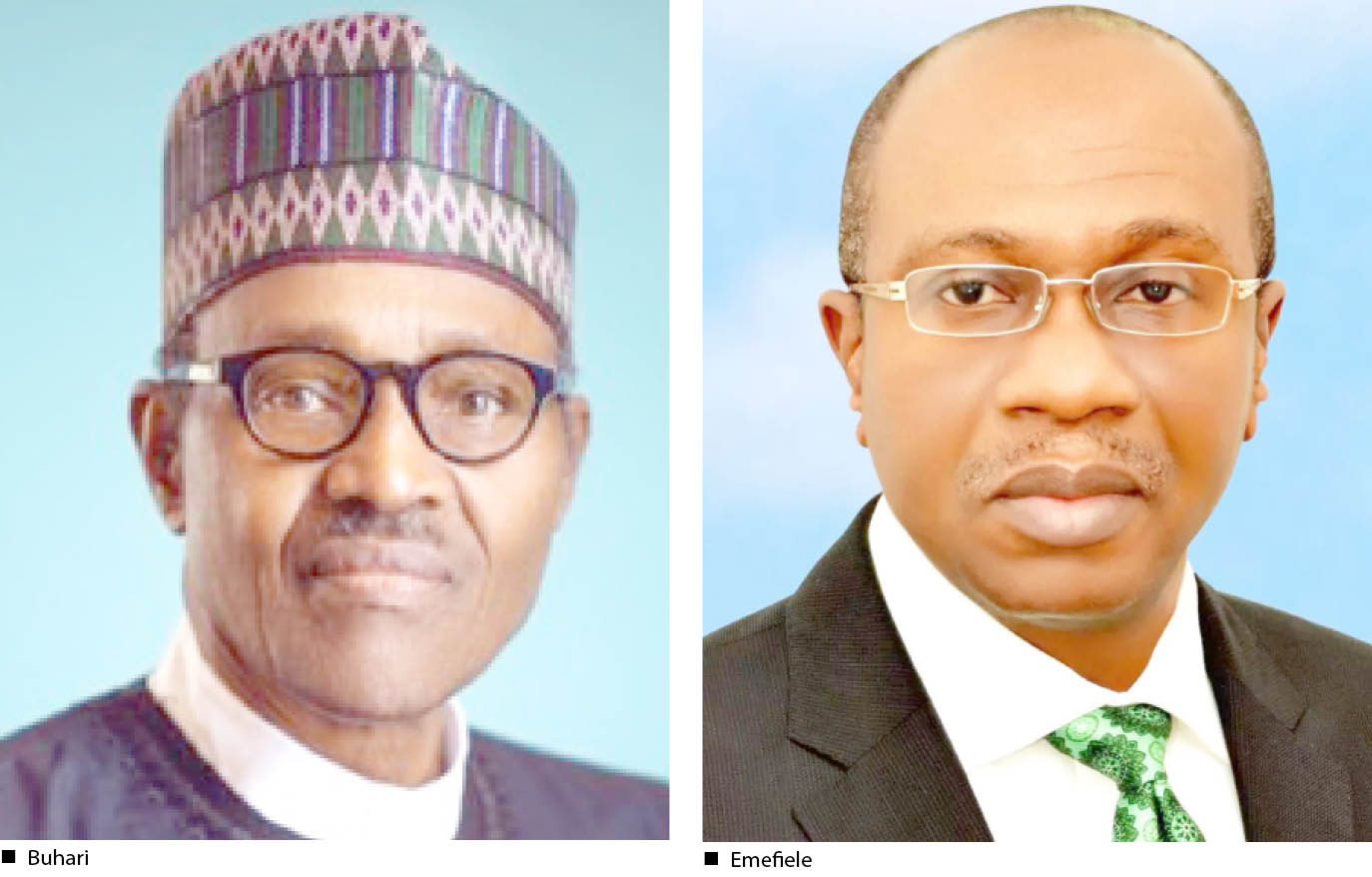

For him, monetary policy by the Central Bank of Nigeria under the current leadership of Governor Godwin Emefiele has failed to achieve its objectives.

“Since Emefiele took over as CBN governor, monetary policy has been sterile. It has not really helped the economy one way or the other,” Adi said.

The CBN has pursued a tight monetary policy to tame inflation. Between January 2022 and January 2023, it moved the Monetary Policy Rate by a whopping 6 percentage points, moving it from 11.5 per cent to 17.5 per cent. Meanwhile, inflation has hardly abated in the country. From 15.6 per cent in January 2022, it rose to 21.82 per cent.

On his part, Brunnermeier says central banks can retain independence only if they promise not to accede to any government desires to monetize excessive debt, forcing authorities to cut spending or increase taxes, or both — so-called fiscal consolidation.

He also counsels that, “the central bank must keep public opinion on its side, because the public is the ultimate source of its power and independence. That means the central bank should effectively communicate the rationale for its actions to retain public support, especially in the face of fiscally driven inflation.”

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.