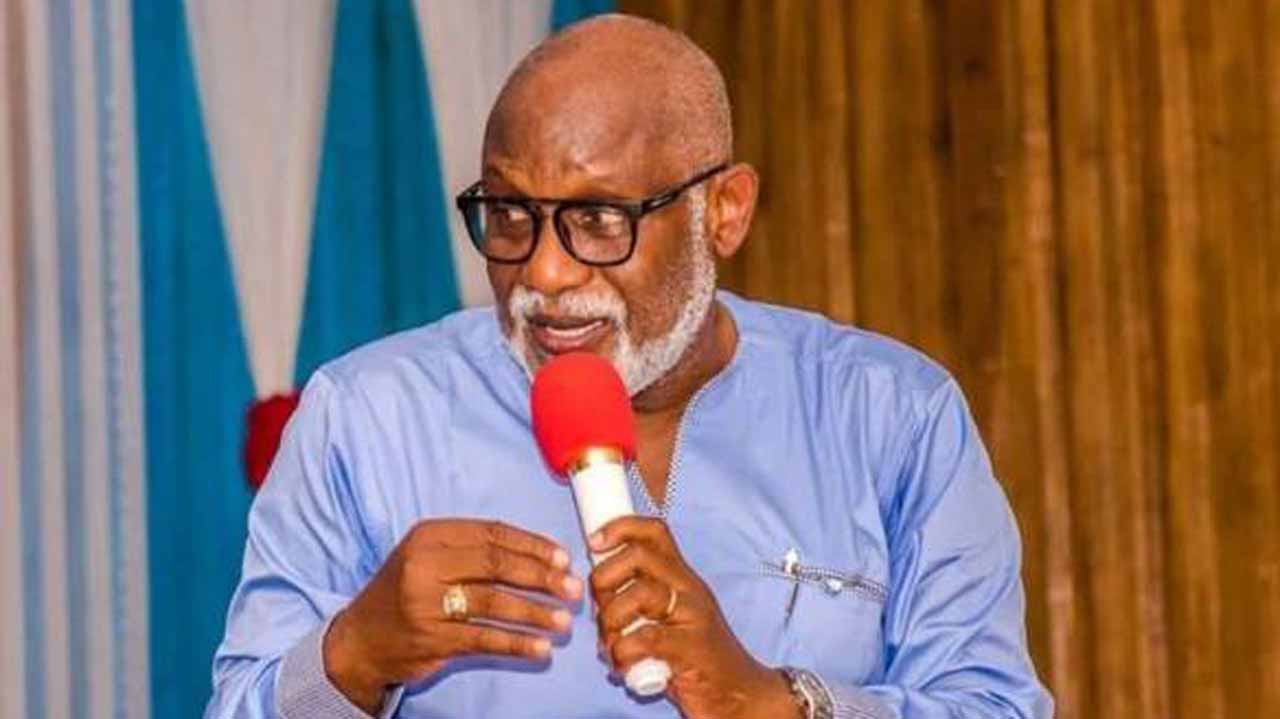

Ondo State seems to only be in the news when the governor spoils for a fight with the powers in Abuja, and Rotimi Akeredolu practises this artfully to appeal to his people. He’s eloquent in his reminders to Abuja that he’s the Chief Security Officer of his state, which is charming confidence, and that he’s not a general with no army. He stood his ground when the Presidency sought to stop South West governors from setting up a provincial security agency, known as Amotekun, and defied the Attorney-General, Abubakar Malami’s declaration that ‘“Amotekun” is illegal and runs contrary to the provisions of the Nigerian law.”

When, in January 2021, alarmed by the spate of killings and kidnapping in his jurisdiction, he asked Fulani herders to vacate the forest reserves in the state, Akeredolu stood up to the Presidency and underlined the permissibility of his action as codified in the Land Use Act of 1978. It’s the path of war his colleagues, especially in the North, had avoided to remain in President Muhammadu Buhari’s good book, and these risks made him a hero to his people.

- BREAKING: Tinubu in closed door meeting with Obasanjo

- Tinubu to meet Obasanjo over presidential bid today

The slippery slope in the performance to make the Fulani the villain has always been the maddening temptation to yield to ethnic profiling, and throwing the Fulani under the bus has become the fad since Buhari came to power. The Fulani ethnic group has been bearing the brunt of the criminal herders, and this narrative has been so popularised across the country that politicians sell anything “Fulani” to their people as the enemy to escape being held to account, for say, refusing to pay workers’ salary or play down scrutiny.

When the June 5 attack on St. Francis Catholic Church in Owo, Ondo State, happened, with about 50 worshippers reported killed, the dog-whistling by politicians in the state was frightening. Social media burst into a flame of accusations to single out Fulani herders as the masterminds, justifying Governor Akeredolu’s wisdom to send the group out of his jurisdiction.

After the Owo attack, a Twitter user with the moniker, Dr Penking, rushed to share that “Few weeks ago, the Governor of Ondo State restricted the activities of Fulani herdsmen in the state. Today, Fulani herdsmen invaded St Francis Xavier Catholic Church Owo, Ondo State and fired sporadically, killing many adults and children (sic),” and then added, in a separate tweet, that “Before you say that the attack at Owo, Ondo State was a coincidence and wasn’t related to restriction of the activities of Fulani herdsmen in the state by Gov Rotimi Akeredolu, remember that Owo is his hometown. They targeted his hometown to kill his kinsmen as payback.”

The popular Twitter user’s sentiment was the mainstream and pervading judgment in a section of the country after the attack, with the nuanced voices on social media left to fight the conspiracy to frame the attack as a Fulani agenda. The lawmaker representing Owo Constituency II in the Ondo State House of Assembly, Olayemi Adeyemi, guided the mob towards the unverified claim and alleged that the attack on the Catholic Church was carried out by armed herdsmen of Fulani extraction.

Such a rush to treat criminals as ambassadors of their ethnic group, religion, region and race or attribute these identities to a crime is dangerous and lazy thinking that has never played out well in any society or system. This mindset inspired the sentiment that the Fulani must be responsible for the Owo attack with no speck of evidence but the sensationalised falsehoods of politicians in search of convenient scapegoats.

Governor Akerodolu’s attempt to make the Fulani the villain of his story was manifest after the Owo attack, and even when the federal government announced that the mastermind was the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), the governor appeared on Channels TV to challenge the claim, alluding that “We just have Fulani herdsmen right in front, followed by these bandits and again ISWAP; so, the three of them work together and they work separately.” Thankfully, this theory too has been deconstructed.

The ethnic profiling animated by the politicians after the Owo attack didn’t only lead to reprisal attacks on the “Hausa community” in Ogwatoghose and Ikare areas of Ondo State, it’s made everyday northerners travelling across the South West the targets of dehumanising searches and premeditated profiling by the Amotekun corps. Last week, a video of Northern travellers whose trucks were intercepted by the Amotekun in Ondo State went viral on social media, and, while this could’ve been an innocent security measure, one of the Amotekun marshals was heard referring to them as “151 suspected invaders”.

Not long after the video generated outrage, the Chief of Defence Staff, General Lucky Irabor, revealed that security forces had arrested the terrorists behind the Owo attack, and none fit the profile imagined by the stereotype artists. He listed the mastermind as Idris Abdulmalik-Omeiza Idris (a.k.a Bin Malik), along with Momoh Otohu-Abubakar, Aliyu Yusuf-Itopa, and Auwal Ishaq- Onimisi. Omeiza, he said, was the culprit behind the June 23 attack on a police station in Adavi LGA, Kogi State, which led to the death of a policeman and theft of weapons.

The terrorists were all identified as Ebira from Okene, instead of what the politicians popularised in their dog-whistling stunts to manufacture the most convenient enemies. What ought to inspire remorse and circumspection in Akeredolu’s bid to manage diversity in his state is, unfortunately, paving the way for an attempt to pathologise another ethnic group and make them appear complicit in the criminal transgressions of their kinsmen.

The seed Akeredolu planted when, on August 14, he asked the Ebira to flush out the criminals among them and “protect their name and integrity in the state,” after meeting some members of the ethnic group, is always the first phase of an agenda to criminalise a group. Our refusal to treat every crime as a transgression by the individual mastermind or resist the rush to attribute identities to a crime fuels the terrifying polarisations all over the country.

No random Fulani or Ebira person owes any Nigerian an apology or explanation for a crime carried out by a member of their ethnic group anywhere, and neither should these criminals be treated as representatives of their group—as though there’s an ethnic gene that powers such criminal affiliations. Owo attack isn’t an Ebira conspiracy; it’s a criminal agenda and only the masterminds must answer for it. What Akeredolu is doing is dog-whistling, and someone must point him to the danger.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.