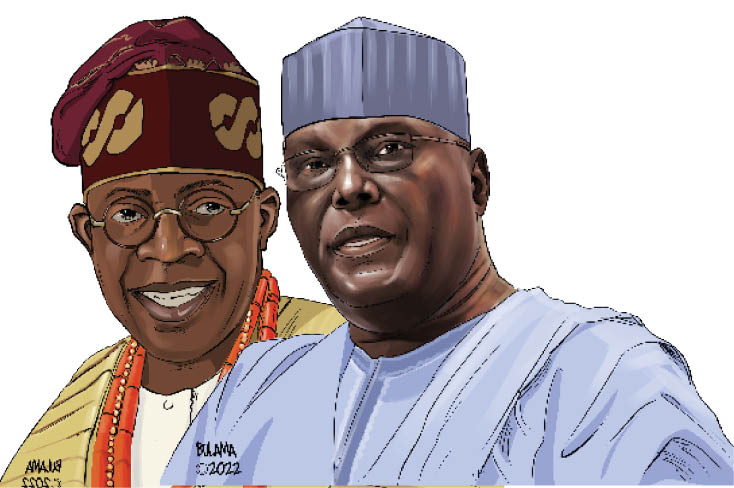

Nigeria has had nine presidential elections since the first in 1979, but scarcely has any thrown up two opponents who match each other in almost every respect like what we are about to witness in next year’s election between former Vice President Alhaji Atiku Abubakar and the former Governor of Lagos State, Alhaji Bola Ahmed Tinubu, the respective candidates of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC).

Both are challengers, with no incumbent power to significantly influence electoral outcomes, even if one is the flagbearer of the ruling party. Both are graduates of the aborted Third Republic politics and remain towering politicians with a staying power unmatched by almost any other politicians in Nigeria since 1999. Both have simply managed to stay politically relevant since then in a way that hardly anyone else in Nigerian politics has managed to do at the same level. Of course, neither man has got to this best-but-last chance easy. They both suffered under Obasanjo’s rather take-no-prisoners approach to politics from 2003 to 2007, and would unite under the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN) banner in the 2007 presidential election. That would not be the first time they have shared the same party, nor the last. They were together in the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in 1992-1993; ACN, and APC in 2015-2016.

Both men also had mentors who were themselves close political and business allies, the late Chief MKO Abiola in the case of Tinubu and the late Major General Shehu Musa Yar’adua for Atiku. Both men are also fabled for having a campaign war chest and a propensity to use it to achieve their life-long ambitions of becoming Nigerian president than any other politician. Tinubu has his famed bullion vans; Atiku his mobile ATMs. Both men also have large businesses across many sectors that help oil their political structures and networks, which themselves stretch across the country. And while Atiku has long pursued his ambition openly in five previous presidential contests, Tinubu has pursued his by stealth, swimming under various political tides to surface this year now that he perhaps thinks the moment is right.

And then, there is a common ideological inclination and approach to leadership. Although both men cut their political teeth in progressive politics of some kind, they are now both firmly in the ‘private sector leads, government follows’ ideological camp. How far such an ideology would go in helping to ensure electoral victory in Nigeria will be tested in this election. Their approach to leadership is also alike, in politics as in business. Neither is actively involved in the day-to-day management of their companies, but rely, instead, on trusted professional managers to do the job.

That model of business leadership is also at the core of their politics and government. Both men are known for recruiting a crop of younger and talented political protégés around them who do most of the political and policy work in the high offices they held. This has meant a wider national network of trusted advisers that is absolutely necessary for anyone running for president, but also occasionally prone to rank betrayal, as either man can tell you.

Finally, and on the softer side of this analysis, both men are married to Yoruba women and are known for their sleek dance moves. Whichever way it goes we can be sure a Yoruba woman will be Nigeria’s next First Lady—for the first time—unless either Peter Obi or Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso springs a wicked surprise. Dance moves, music and entertainment of all kinds will also be influential in this campaign, even if they cannot determine it, so more sleek moves from the pair lay ahead. How, then, will the contest be decided? I cannot speak of what tomorrow holds. But in this unique contest between two candidates who share so much in common, I can think of three to four things that, all other things being equal, could decide the election one way or another.

The first is most obvious: the choice of running mate for either candidate. This is a bigger problem for Tinubu than it is for Atiku. In the geopolitical arithmetic of presidential elections in Nigeria, a Muslim candidate from the South West is at a considerable disadvantage. A Christian running mate from the North might depress northern Muslim votes; a Muslim running mate will depress all Christian, at least so goes the theory. But the practice might yet be different because while the former has not yet been tested, the latter held against the theory in 1993. It might yet hold still.

For Atiku, his best choice would have been his running mate in 2019, Peter Obi. But Peter Obi now has a large army of social media enthusiasts—more than any other candidate in this election so far—who cannot accept anything less than a run for the presidency by their man. This makes the situation dicey for Atiku because Peter Obi can drain away support from the South East, the region that gave him the most votes in 2019. This takes us to another issue that can decide the election: electoral base.

In his memoirs, the late President Shehu Shagari said a Nigerian presidential candidate must first have an electoral base of support of his own, something like a home support in football that will back you against other teams come rain or shine. Tinubu has more strengths here than Atiku. Yoruba political behaviour in Nigerian presidential elections is simple: they will vote massively for the Yoruba presidential candidate with the highest chance of winning it. They are not much interested in anything else in Nigeria’s national politics, due to a long tradition of ‘opposition politics’, whatever that means in our political context here.

The 1999 election was an exception that yet proved the rule because the two candidates were Yoruba. So, we can expect Tinubu to do handsomely in the six states of the South West—the second highest in electoral strength in the country—in the presidential election, regardless of the fact that Yoruba politics is more divided now than in 1999, and regardless of pockets of PDP support in the region. That’s almost certainly six states in the bag for Tinubu from the home front.

On the other hand, Atiku has never really had an electoral base of the kind under discussion here. In his two previous general election contests in 2007 and 2019, his largest share of votes had come from the South West and South East respectively, not anywhere in the North, his original home front. On both occasions, he lost the northern votes to the late President Yar’Adua and Buhari. But in Nigerian politics, you either already have an home front, or you borrow it from allies who have it. And since the only other northern candidate in the race, Kwankwaso, who cannot be dismissed, but who is still no match for either Atiku himself or Tinubu, the former vice president now has an opportunity to cultivate his electoral base, even if he must come up against those northern politicians who are willing to lend their home base support to Tinubu.

And then, there is the small but significant issue of how the new electoral act will influence the entire campaign. The long campaign season is a novelty in Nigerian politics. This novelty will mean several things for presidential candidates particularly, depending on the foresightedness of their campaign managers and parties. The challenge is how to run a cost-effective campaign that will deliver victory over the many months ahead? Campaigns that can answer this question effectively will stand a better chance because brief stop-overs at mass rallies in a few state capitals and regional hubs that our politicians are used to will no longer do the trick.

This is why, in my view, this will be Nigeria’s first policy campaign. The candidate with the most edge will be the one who can tell Nigerians not just what they will do but how they will do it when in office and who will do it. But here I rest my case.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.