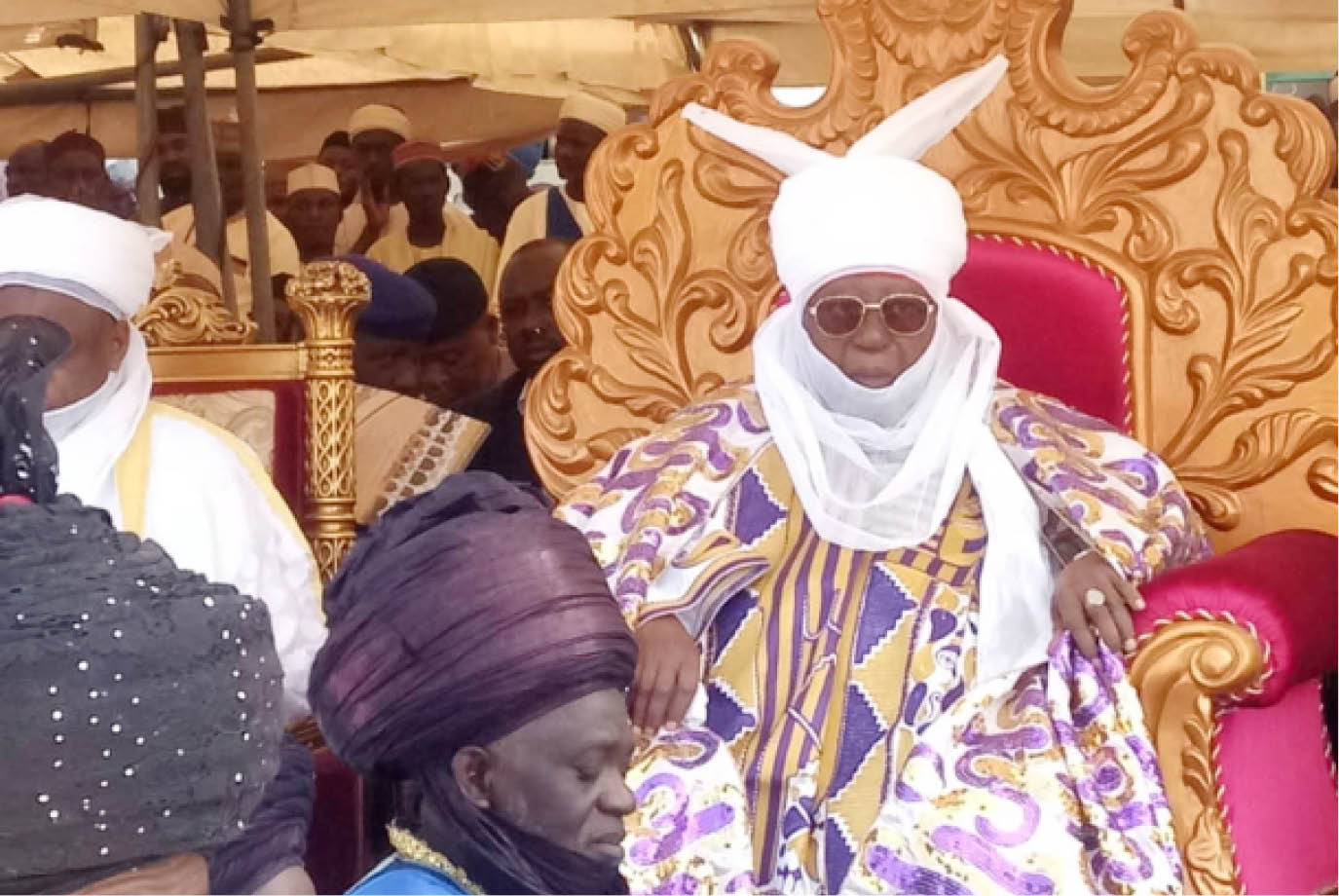

VIPs from all over the North, from across the country and from abroad congregated in Zaria at the weekend to felicitate with the Emir of Zazzau, Alhaji Shehu Idris, who marked 45 years on the throne. He is the longest reigning monarch in the history of the very old Zazzau throne, and his reign has been long, mostly peaceful, sometimes turbulent and very eventful.

A traditional ruler’s throne is the most enigmatic public office in Nigeria. Although it is not mentioned anywhere in the voluminous 1999 Constitution, it receives great deference from people whose public offices received elaborate constitutional mention. The throne has no term limits; it is the only public office in Nigeria which has a life tenure. Compare that to military service chiefs, who some people are saying have overstayed after only five years in office. Think of permanent secretaries and directors, who must retire after 35 years in service, 60 years of age or even eight years on the same job. Think of ministers and commissioners, who live from one cabinet reshuffle to another; senators and Reps, who live from one election circle to another, with no tenure limit but with an 80% casualty rate in every election; as well as governors and president, who must serve a maximum of eight years.

Forty five years on the throne is one of the longest reigns for current Northern emirs and chiefs. In comparison, the Sultan has been on the throne for 13 years; Shehu of Borno for 11; Emir of Gwandu for 14; Emir of Kano for 5; Emir of Katsina for 11; Aku Uka of Wukari for 42; Etsu Nupe for 16; Tor Tiv for 2; Lamido of Adamawa for 9; Emir of Bauchi for 9; Emir of Ilorin for 24; Sarkin Zazzau Suleja for 20; Attah Igala for 7 years. Only Emir of Kontagora Alhaji Sa’idu Namaska has been on the throne longer, for 46 years.

Some Northern emirs and chiefs from an earlier era reigned for longer periods. Among the longest reigning monarchs of modern times, Sultan Abubakar III reigned for 50 years; Emir of Kano Ado Bayero for 51 years; Emir Muhammadu Bashar of Daura for 41 years; Lamido Adamawa Aliyu Mustapha for 57; Attah of Igala Aliyu Obaje for 56 and Chief of Kagoro Malam Gwamna Awan for 63 years. Sarkin Katagum Muhammadu Kabir reigned for 37 years; Emir of Lafia Mustafa Agwai reigned for 43 years and Bashar’s grandfather, Emir of Daura Abdurrahman, reigned from 1911 to 1966.

Unlike other public officers, an emir is never transferred. He gets no promotion, though some thrones are upgraded to second or first class. Emirs do not reshuffle their councils, though some title holders could get promoted to a higher title. Alhaji Shehu Idris was a young man of 39 when he became Emir of Zazzau in February 1975. His was little known outside Zaria, unlike in the modern day when Army Generals, Police DIGs, a Customs Controller General, a former CBN governor, a Supreme Court judge, an Appeals Court judge and even a former governor with well-known names become emirs and chiefs.

Men who become traditional rulers from rigid careers such as the army take some time to adjust. In November 2006 when Brigadier General Muhammadu Sa’ad Abubakar was appointed Sultan of Sokoto, the Army Chief General Martins Luther Agwai was out of the country. As soon he returned, he went to Sokoto to congratulate his former officer. The new Sultan, only days old on the throne, sprang to his feet when the Army Chief walked in, much to the annoyance of old palace courtiers. In 1993 when, as a reporter for Citizen magazine I visited the newly installed Emir of Suleja Malam Auwal Ibrahim, I wrote in my story that “for a man who once sat on a governor’s chair, the Suleja emir’s throne, made up of a mat surrounded by a few traditional pillows, did not look very inviting.” Yet, Malam Auwal Ibrahim coveted it all his life, so there must be something to it.

So did Major General Muhammadu Iliya Basharu, an Army General, former GOC of the Army’s 2 Division and two-time military governor of old Gongola State. Several times in the 1990s when I visited him in his Kaduna home, the subjects that interested him the most was traditional leadership, the difference between political rulers and traditional leaders, and how the two terms were often mixed up.

For people in the North, nothing popularized Sarkin Zazzau Shehu Idris quite like the praise song in his honour by the late Alhaji Mamman Shata. Shata used the catchiest of phrases, idioms and picturesque allusions to describe Shehu Idris, including baobab tree that adorns a town; bull elephant that defies all traps; buffalo, the cow on the loose; roan antelope that does not suffer confusion because of an archer; and the camel among emirs.

Alhaji Shehu Idris was appointed to the throne by the military governor Brigadier Abba Kyari in 1975. Since then, he has reigned alongside 20 governors, nine of them civilians, eleven of them soldiers. They included Abdulkadir Balarabe Musa, the most radical civilian governor ever produced in Nigeria, and Major Abubakar Dangiwa Umar, who The Economist of London described at the time of his appointment as “a young leftist Major.” Alhaji Shehu Idris survived all of them and was never threatened with deposition or even issued a query, as far as the public knows.

In Zaria, there is cut-throat competition for the throne among its three great ruling houses, the Barebari, Mallawa and Shehu Idris’ Katsinawa. To their credit, these ruling houses keep their competition below the radar and it hardly bursts into the open, thanks to Alhaji Shehu Idris’ adroit balancing act which preserves each ruling house’s titles and privileges. Inter-marriage among them also helps to ease the competition.

During Shehu Idris’ reign, the state’s name changed from North Central to Kaduna State. Katsina State also split from Kaduna State in 1987. While this removed the fierce rivalry between Katsina and Zazzau, it replaced it with political and sometimes physical conflict between southern and northern Kaduna State. Northern versus Southern Kaduna dichotomy often resulted in ugly sectarian riots. The worst ones were the Kafanchan riot of 1987, two rounds of Zangon Kataf riots in 1992, two Shari’a riots of 2000 AD as well as the post-election riots of 2011 and 2012. Rivalry and conflict also persist in politics and in public service appointments.

Emir Shehu Idris did what he could, behind the scenes and sometimes in front of the scenes, to curb the violence. In 2001, we reported in New Nigerian that the emir personally rushed to the scene when he heard that youths at Tudun Wada area were about to start a riot. The boys took to their heels when they saw the emir, even though he was escorted by only a few unarmed traditional bodyguards.

During his reign, many chiefdoms were excised from Zazzau Emirate to become independent. Following one such exercise in 2001, some Muslim areas also agitated to become independent emirates but Governor Ahmed Makarfi told me in his office at that time that while he understood the agitation by minority, non-Muslim areas for traditional autonomy, he will not agree to excise any Muslim area from Zazzau Emirate.

The longevity, stability, restraint, non-involvement in politics, wisdom and studious avoidance of controversy by emirs such as Alhaji Shehu Idris greatly aided the durability and respectability of traditional thrones in the North. In the years that Idris has been on the throne, a Sultan was deposed; emirs were deposed in Gwandu, Muri, Agaie, Bade and Suleja; an Etsu Nupe was deposed and many lesser chiefs were deposed all over the North. Surviving on the throne for 45 is a great feat. May Alhaji Shehu Idris reign for many more years in peace and in good health.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.